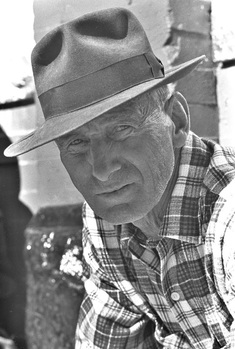

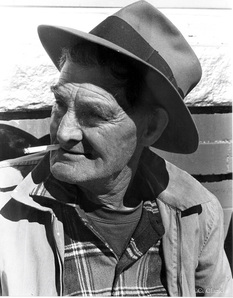

After Work--Time to Play in a Mining Camp, © Charles Clark, Click to Enlarge.

After Work--Time to Play in a Mining Camp, © Charles Clark, Click to Enlarge.

A DAY IN THE LIFE OF A MINER

By Charles (Chuck) Clark ©

A few friends of my era have contributed valuable words to this vignette. They worked as miners in the inky black bowels of the earth beneath tons of rock. Some were young, virile men who had just graduated from high school and this was one of their first real jobs. Some were part-time jobs while going to college; others were full-time bread winners for their families. Some had never worked underground before, but they had parents or relatives who were miners.

In the early days (late 1800s) one of the quickest ways to get a job in the mine was to take on the toughest man on a crew in a fistfight and attempt to beat him into submission. One of these individuals was Jack Dempsey, the Manassa Mauler, who had little difficulty earning a job. As miners became more civilized, the way one got and KEPT a job was to work hard and keep one’s mouth shut and one’s eyes open.

Life underground was very dangerous and a mistake could end one’s life in a flash. Each miner had his co-workers back if he recognized a danger. This didn’t always work, but many lives were saved by recognizing dangerous situations and alerting a co-worker to the danger. One of the hardest situations to adapt to was the darkness with only a small carbide, or later, a battery operated light. This was a safety trade-off as the carbide light would fail when bad air was encountered.

In the winter, the trek to work was in the dark and the end of the day shift was about the same. Miners lived in a near dark environment most of the time. If that tiny light failed for some reason, panic ensued. One friend, Myron House, experienced this and had to find his way to another station by guiding his feet along the tram tracks until he came to a lighted section of the mine. By his own admission, he was terrified, though at the time, he hid his fear!

Other dangers were the result of a misfire in the round of explosions that were required in the search for veins of gold. Usually there were patterns of explosions that resulted in confirmation of a level. Dynamite was delivered to the powder man who had the expertise with explosives. In the early days, the delay in the charge was determined by the length of the fuses. Each was lit with a delay that determined the shape of the explosion. More recently, the detonator that initiated the explosion was determined by the electrical delay of the detonator. The miner counted the number of explosions to make sure all charges went off. If the explosions were not counted, there was a possibility of drilling into a live round when the next shot was activated. Newbies carried the explosives to the head of the shot and mucked the broken rock into motors (trams).

Since the majority of the mucked rock was worthless, it was taken to the skip or bucket and transported to the surface and discarded on the ore dump. Paying ore went to the ore house and was sorted by values that were determined by an assayer. This was accomplished in an assay shop. In Victor there were several assay shops. Kohlberg and Page were the most well known. In the early days a rider picked up samples on horseback and carried them to the assayer and returned the result of the test back to the mine owner or superintendent of the mine. Later, the telephone accomplished the same function. Valuable ore was shipped to a mill and refined for gold. If rich enough a guard accompanied the ore to the mill.

If a rich vein was discovered, some miners carried unusually good pieces home in their “pie cans”, clothing, or body cavities. This was called “hi-grading” and if caught by management, was cause for being blackballed from working in a mine again. Even though the penalty was great, “hi-grading” persisted to the end, as miners’ top salaries were so pathetically small in the early days ($1.00/hour or $8.00 per 10 to 12 hours per day). Some miners bought clothing and groceries with good specimens. It took a very rich specimen to buy anything, as the price of gold prior to 1939 was $25.00 a troy ounce, the going price of a pair of boots.

Because life was a series of horrors without rewards, miners drank heavily to forget the bad times. They would spend what little money they had on 10-cent beer and stay all night in Zekes, the Stope, the Amber Inn, or the Gold Coin where they could commiserate with their buddies about the rough day they had. In some cases, they closed the bar and as one miner stated, “The one who was the least drunk ran the hoist the next morning.” This indicated that safety went to the least drunk miner, which was not what many miners wanted to hear. That was the way it was in the early days in mining and surprisingly, safety didn’t suffer greatly as a result. The EPA and OSHA would have been horrified. Not all miners drank to excess, however, but their stories evaporated into nothingness and didn’t make the headlines or the obituary column.

By Charles (Chuck) Clark ©

A few friends of my era have contributed valuable words to this vignette. They worked as miners in the inky black bowels of the earth beneath tons of rock. Some were young, virile men who had just graduated from high school and this was one of their first real jobs. Some were part-time jobs while going to college; others were full-time bread winners for their families. Some had never worked underground before, but they had parents or relatives who were miners.

In the early days (late 1800s) one of the quickest ways to get a job in the mine was to take on the toughest man on a crew in a fistfight and attempt to beat him into submission. One of these individuals was Jack Dempsey, the Manassa Mauler, who had little difficulty earning a job. As miners became more civilized, the way one got and KEPT a job was to work hard and keep one’s mouth shut and one’s eyes open.

Life underground was very dangerous and a mistake could end one’s life in a flash. Each miner had his co-workers back if he recognized a danger. This didn’t always work, but many lives were saved by recognizing dangerous situations and alerting a co-worker to the danger. One of the hardest situations to adapt to was the darkness with only a small carbide, or later, a battery operated light. This was a safety trade-off as the carbide light would fail when bad air was encountered.

In the winter, the trek to work was in the dark and the end of the day shift was about the same. Miners lived in a near dark environment most of the time. If that tiny light failed for some reason, panic ensued. One friend, Myron House, experienced this and had to find his way to another station by guiding his feet along the tram tracks until he came to a lighted section of the mine. By his own admission, he was terrified, though at the time, he hid his fear!

Other dangers were the result of a misfire in the round of explosions that were required in the search for veins of gold. Usually there were patterns of explosions that resulted in confirmation of a level. Dynamite was delivered to the powder man who had the expertise with explosives. In the early days, the delay in the charge was determined by the length of the fuses. Each was lit with a delay that determined the shape of the explosion. More recently, the detonator that initiated the explosion was determined by the electrical delay of the detonator. The miner counted the number of explosions to make sure all charges went off. If the explosions were not counted, there was a possibility of drilling into a live round when the next shot was activated. Newbies carried the explosives to the head of the shot and mucked the broken rock into motors (trams).

Since the majority of the mucked rock was worthless, it was taken to the skip or bucket and transported to the surface and discarded on the ore dump. Paying ore went to the ore house and was sorted by values that were determined by an assayer. This was accomplished in an assay shop. In Victor there were several assay shops. Kohlberg and Page were the most well known. In the early days a rider picked up samples on horseback and carried them to the assayer and returned the result of the test back to the mine owner or superintendent of the mine. Later, the telephone accomplished the same function. Valuable ore was shipped to a mill and refined for gold. If rich enough a guard accompanied the ore to the mill.

If a rich vein was discovered, some miners carried unusually good pieces home in their “pie cans”, clothing, or body cavities. This was called “hi-grading” and if caught by management, was cause for being blackballed from working in a mine again. Even though the penalty was great, “hi-grading” persisted to the end, as miners’ top salaries were so pathetically small in the early days ($1.00/hour or $8.00 per 10 to 12 hours per day). Some miners bought clothing and groceries with good specimens. It took a very rich specimen to buy anything, as the price of gold prior to 1939 was $25.00 a troy ounce, the going price of a pair of boots.

Because life was a series of horrors without rewards, miners drank heavily to forget the bad times. They would spend what little money they had on 10-cent beer and stay all night in Zekes, the Stope, the Amber Inn, or the Gold Coin where they could commiserate with their buddies about the rough day they had. In some cases, they closed the bar and as one miner stated, “The one who was the least drunk ran the hoist the next morning.” This indicated that safety went to the least drunk miner, which was not what many miners wanted to hear. That was the way it was in the early days in mining and surprisingly, safety didn’t suffer greatly as a result. The EPA and OSHA would have been horrified. Not all miners drank to excess, however, but their stories evaporated into nothingness and didn’t make the headlines or the obituary column.

|

Bars were the social clubs for the miner. If a miner was hurt or killed in an accident, the other miners would “pass the hat” and collect money for the family and take care of them until the miner could resume work or until the family could survive on their own. Word traveled quickly in the bar when jobs were available, or when a mine was closing, or if a boss that no one liked or was not respected was fired. Some called this gossip and some called it “essential news.” In either case, miners knew things that were important much more quickly than one might expect.

|

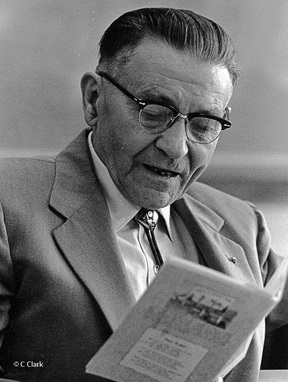

Rufus Porter -- Hard Rock Poet. As hard rock gold mining activities declined, Rufus Porter transitioned with greater success than most hard rock miners to another career as a writer and poet. Click the highlighted link to learn more about his remarkable life. © Charles Clark.

Rufus Porter -- Hard Rock Poet. As hard rock gold mining activities declined, Rufus Porter transitioned with greater success than most hard rock miners to another career as a writer and poet. Click the highlighted link to learn more about his remarkable life. © Charles Clark.

It seems that there was a lack of spiritual activity in a mining town. This was not true in Victor, Colorado. There were a multitude of churches in the District. How many was not certain, but in Victor alone in the 50’s there were at least six regularly attended churches. There was a Catholic Church, a Baptist Church, a Christian Scientist Church, an Episcopalian Church, a Lutheran Church, and a Presbyterian Church. Church services were regularly attended by women, but not so regularly attended by the male population of miners. In asking several miners why they did not attend church, the majority of miners suggested that Sunday was their only day of rest, but that they were represented by the family. Bible School, communion, Ladies Aide Society and other church sponsored activities were well attended. Not all miners were bar cruisers and set proper examples for their families. The Catholics and the Scandinavian segments of the population seemed to be the most regular in attending church. Some had hints that God would bring hope for them. This, sadly, took, a long time. Most of the old timers passed away before Victor was revived. The miners had to move out of their community to procure a job. This was terribly difficult as miners liked to plant roots in a community. This meant leaving not only the job, but also meant leaving long time friends, fraternal organizations (of which Victor had a number) and all of the associations related to long-term employment and residency. One miner said his main regret was not being able to count on a doctor as well qualified to deal with miners’ wounds as was Dr. Denman. Some were worried about establishing credit at the hardware and grocery stores, and were worried about feeding their families. Among the more resilient, Rufus Porter left the Mining District to find fame with success in a new career as a writer and a poet.

Closing the mines was truly a sad day in Victor’s history. Grocery stores, hardware stores, movie theatre, auto dealerships, and a myriad of other shops disappeared one after another.

It was heart breaking to watch as a resident of the City of Mines saw friends, classmates, and businessmen move to a distant town where he could no longer talk to, interact with, or even say “hello” to while walking to school in the morning.

Victor died that day, as did a number of souls. Watchmen took over on the mines and even they disacppeared after time. The mines were swallowed by time. Most are now large pits in the ground with only a few memories to remind those that care what a glorious place Victor was. The reason was the character of the miner—God bless his Granite Soul!

© Charles (Chuck) Clark

Closing the mines was truly a sad day in Victor’s history. Grocery stores, hardware stores, movie theatre, auto dealerships, and a myriad of other shops disappeared one after another.

It was heart breaking to watch as a resident of the City of Mines saw friends, classmates, and businessmen move to a distant town where he could no longer talk to, interact with, or even say “hello” to while walking to school in the morning.

Victor died that day, as did a number of souls. Watchmen took over on the mines and even they disacppeared after time. The mines were swallowed by time. Most are now large pits in the ground with only a few memories to remind those that care what a glorious place Victor was. The reason was the character of the miner—God bless his Granite Soul!

© Charles (Chuck) Clark

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Charles (Chuck) Clark was born in Colorado Springs, Colorado in 1933. His father was a grocer and his mother was a teacher. He was raised in Victor, graduated from Victor High School in 1951, and four years later graduated from the University of Colorado with a degree in English Literature and a Commission as an Ensign in the U.S. Navy. Later he received a Masters Degree from Colorado College.

After his service obligation and becoming a pilot, Chuck was a teacher, probation officer, photographer, marketing manager and vice president of several companies. He traveled to Peru twice and accumulated and sold numerous photographs of the Amazon and its indigenous people. In 2011, he was elected a Member of the famed National Explorer's Club headquartered in New York City. He is the second Victorite to gain membership in the exclusive Explorer's Club. The first was Lowell Thomas.

Chuck recorded many of the experiences he had as a child in Victor in a 2011 book titled "Memories of a Wonderful Childhood in Victor, Colorado" -- which can be obtained from the gift shop of the Victor-Lowell Thomas Museum or ordered online.

This vignette about "A Day in the Life of a Miner" (not included in Chuck's book) was submitted in May, 2016 in tandem with Myron House's memories about his "Underground Mining Experiences at the Cresson and Ajax". Click the link.

Charles (Chuck) Clark was born in Colorado Springs, Colorado in 1933. His father was a grocer and his mother was a teacher. He was raised in Victor, graduated from Victor High School in 1951, and four years later graduated from the University of Colorado with a degree in English Literature and a Commission as an Ensign in the U.S. Navy. Later he received a Masters Degree from Colorado College.

After his service obligation and becoming a pilot, Chuck was a teacher, probation officer, photographer, marketing manager and vice president of several companies. He traveled to Peru twice and accumulated and sold numerous photographs of the Amazon and its indigenous people. In 2011, he was elected a Member of the famed National Explorer's Club headquartered in New York City. He is the second Victorite to gain membership in the exclusive Explorer's Club. The first was Lowell Thomas.

Chuck recorded many of the experiences he had as a child in Victor in a 2011 book titled "Memories of a Wonderful Childhood in Victor, Colorado" -- which can be obtained from the gift shop of the Victor-Lowell Thomas Museum or ordered online.

This vignette about "A Day in the Life of a Miner" (not included in Chuck's book) was submitted in May, 2016 in tandem with Myron House's memories about his "Underground Mining Experiences at the Cresson and Ajax". Click the link.

THE PAST MATTERS. PASS IT ALONG.

The Next Generation Will Only Inherit What We Choose to Save and Make Accessible.

Please Share Your Memories and Family Connections to Victor & the World's Greatest Gold Camp by

Contacting Victor Heritage Society, PO Box 424, Victor, CO 80860 or e-mail [email protected].

The Next Generation Will Only Inherit What We Choose to Save and Make Accessible.

Please Share Your Memories and Family Connections to Victor & the World's Greatest Gold Camp by

Contacting Victor Heritage Society, PO Box 424, Victor, CO 80860 or e-mail [email protected].

VictorHeritageSociety.com

Copyright © 2023 Victor Heritage Society. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright © 2023 Victor Heritage Society. All Rights Reserved.