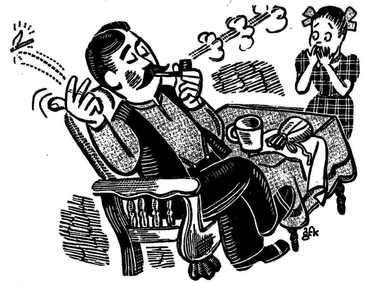

This illustration of Papa casually tossing a match after lighting his pipe accompanied Gertrude Moore McGowan's story, "Paying The Piper," when it was published in the June 1973 issue of GOOD OLD DAYS MAGAZINE.

This illustration of Papa casually tossing a match after lighting his pipe accompanied Gertrude Moore McGowan's story, "Paying The Piper," when it was published in the June 1973 issue of GOOD OLD DAYS MAGAZINE.

PAYING THE PIPER: It was't fair, but "We are women," was Mama's only comment. Childhood Memories and Lessons Learned Growing Up in Victor, Colorado in the Early 1900's.

By Gertrude Moore McGowan (1905-1992). Published in GOOD OLD DAYS MAGAZINE, June 1973.

Submitted by Nancy McGowan Galbraith (daughter).

Papa drained the last swallow of coffee from the heavy mug that was exclusively his. After carefully wiping his mouth and the ends of his moustache with a napkin, he leaned back in his big arm chair and filled his pipe from the brown leather pouch. He thoroughly tamped the tobacco down, struck a match, puffed vigorously till the smoke started to curl upward, shook the match, then tossed it over his shoulder.

I screamed as the match, which showed no flame when it left his hand, burst into one last flicker as it flew through the air, and landed on the pile of white georgette crepe on Mama’s sewing machine.

Mama almost beat the match to the machine when she saw what was happening. But she wasn’t quick enough. “Oh, it’s burned Wilma’s dress,” she moaned. “It’s a miracle the whole thing didn’t go up in flames, but look—there are two big holes, one in the waist and one in the skirt.”

Mama held the burned dress high, spreading the full skirt. “Sister, why didn’t you put it back in the box when you set the table? You know I never leave my work out. It’s ruined, and graduation is tomorrow night. Oh, Henry, I’ve asked you dozens of times not to flip your matches!” Mama, who never cried, looked like she was ready to.

“It would’ve gone into the waste-basket like always if you hadn’t had that stuff in the way,” he answered, scowling at me.

“I knew Mama was going to finish it after supper. That’s why I didn’t bother to put it away,” I sobbed. “I didn’t think it would hurt to leave it out for a few minutes.”

Mama dug frantically through the scraps, trying to find one big enough to replace the burnt pieces. But it was expensive material and the yardage had been figured carefully. The pieces were all little ones.

“Well,” she sighed, “there’s nothing to do but buy some more goods, provided Schillings have any left, and make it over tonight. It’s lucky Mrs. Swanson bought it here in town instead of out of the catalog.”

Mama’s making Wilma’s graduation dress was just one of the neighborly things such as the women in our block just naturally did for each other. Passing the bread starter around, and trading loaves of home-made bread so several families could have fresh bread on only one was another. Helping with the children when there was a new baby or somebody sick was just routine.

Since graduation from high school was not the commonplace thing then that it is now, the whole neighborhood shared in the Swanson family’s pride in Wilma’s accomplishment. Each family in our block was helping in some way, knowing full well that with seven younger children, the Swansons couldn’t spend much on the oldest.

“We’ve got no money to give to the Swansons,” Papa objected. “Making the dress, if you want to, is one thing, but buying goods is another. You know how close run we are.”

“I should know,” Mama, who never let anything disturb her, snapped. “I’m the one who makes over clothes and cooks the cheap cuts and dried fruits and beans to keep the bills down. And I’m the one who did the work on the dress instead of buying a gift, because we’re the only ones in the neighborhood not buying something for Wilma.”

“True,” sputtered Papa, “but why should I have to pay out good money just because you want to be neighborly?”

“Remember it was your carelessness that caused the fire,” Mama called from the bedroom where she had gone to change into her street clothes. “But don’t worry, I’ll buy the goods out of my coat money that I’ve been saving from sewing. Wilma has to have her dress tomorrow.”

Papa, unperturbed, went into the front room and was immediately lost in his magazine. If the roof had come off, he wouldn’t have known it. Mama took one of the small pieces of material for a sample, got her handbag from the sideboard drawer and gave me my orders.

“Sister, you get the table cleared and the dishes done while I’m gone. I’ve not much more than time to get to the store before it closes at six.”

“Why can’t John help?” I complained, but I was talking to myself, for Mama was briskly walking out the front door and John, along with the older boys, had quietly disappeared while stuffing the last cookie into his mouth. That was the trouble being the only girl in the family. I was the one who had to help with housework.

A little breathless from hurrying, Mama was back before the dishes were done. She lost no time in changing back to her house dress before cutting into the new material. She would no more have worn dress-up clothes around the house than she would have appeared in a store wearing a house dress.

The dining table, extended by three leaves to accommodate the eight of us at mealtime, gave her plenty of working space. Her sewing machine stood in the corner. She made practically all of the boys’ clothes and all of mine, many of them hand-me-downs from my aunt who had no children of her own. Besides that, she did a lot of sewing for people better fixed than we were who could afford a sewing woman, so there weren’t many days when the machine wasn’t used.

She lost no time putting me to work with scissors, ripping the seams while she cut the new pieces. There was a lot of ripping. Snip and pull, snip and pull! It was slow going with the scissors, and her cutting was done long before I had any piece ripped apart. Then she cut the threads with a razor blade while I held the material and it didn’t take long to finish the ripping.

“It isn’t fair,” I complained as it got darker outside and I heard the other children playing their games out in the street. “I’m losing my after-supper play time. Nobody else has to stay in and work on a silly old dress.”

“You’re paying the piper,” Mama explained patiently. “Just that one little neglect of your duty was the cause of all this. Papa’s match wouldn’t have caused any damage if the dress had been put in its box.”

I didn’t know who the piper was, nor how I was paying him by working, but there were lots of Mama’s saying I didn’t understand.

“But Papa isn’t doing anything to help,” I objected. “He isn’t even having to pay for it out of his own money.

Mama smiled faintly. “We are women,” was her only comment.

Eventually the boys were called in and hustled off to bed, and still we worked. After the ripping was done, I basted and Mama stitched. On ordinary things she didn’t baste, but this was very special, so the basting was important. It was the first time she had let me work on anything nice that she was making, and a little glow of pride warmed me.

About ten she stirred up the kitchen fire and made cocoa and we had a little party, just the two of us, with cookies and cocoa. We invited Papa to join us, but he was still reading his magazine and waved us away. After we finished eating I washed and dried the dishes and put them in the cupboard while Mama did the last stitching on the blouse.

“I’m sleepy, Mama,” I said. “Can’t we finish it in the morning?”

“You know we can’t. There will be breakfast and dishes, then straightening up the front room and making beds. Wilma will want to try it on early to be sure everything fits. No, it will have to be done tonight. Now, you take the blouse and snip the basting threads every couple of inches and pull them out carefully. Don’t try pulling the whole length by the knot because it might be caught in the stitching and cause a snag. When you’re through with that, pull all the ends of the threads through to the underside and tie them neatly; then cut them off.”

She patted my shoulder and smiled. “It won’t take much longer, dear. You’ve been such a help to me. I couldn’t ever have done it without you. You may sleep a little later in the morning.

Removing the bastings wasn’t so bad, but it seemed like there would be no end to the threads to tie. Every time I thought they were all done, Mama would look it over and find some more. Some women stitched back and forth several times at the beginning and end of seams, but Mama considered that sloppy sewing.

I almost fell asleep in my chair while Mama stitched the waist and skirt together and made the placket. That done, she said, “Come on, Sister, wake up and we’ll get this done in short order. I’ve marked the places for hooks and eyes. You sew them on while I put in the hem. It’ll take me longer because the skirt is so full, but you may go to bed as soon as you’re through.”

My eyes kept closing and I stuck the needle in my fingers as often as I did the cloth, but finally finished.

Mama looked approvingly at my work. “That’s fine, dear. Now you may go to bed,” she said, “and we must be sure not to talk about this. We wouldn’t want the Swansons to know that we had been caused any inconvenience. It would make them feel bad and we don’t want anything to spoil their big day. You’ll remember that, won’t you?”

I nodded, yawing. “I’ll remember,” I promised, and stumbled toward my bedroom.

At the moment I was too sleepy even to realize what I was supposed to remember. But the next day brought the excitement of the first graduation ceremonies I had ever seen, and a secret feeling of pride that I had shared in helping make it a lovely occasion.

That long evening’s work, done so unwillingly, stands out in my memory after all these years. I remember the important feeling I had that even a little girl like myself could help to set matters right in a world where things were not always fair.

The sudden, unpredictable calamity that could follow neglect of one’s duty, however slight, was self evident at the time, as well as the necessity for teamwork in doing promptly what must be done. However, full understanding of Mama’s smiling “We are women” is something that came gradually only after years of living, loving, and learning.

By Gertrude Moore McGowan (1905-1992). Published in GOOD OLD DAYS MAGAZINE, June 1973.

Submitted by Nancy McGowan Galbraith (daughter).

Papa drained the last swallow of coffee from the heavy mug that was exclusively his. After carefully wiping his mouth and the ends of his moustache with a napkin, he leaned back in his big arm chair and filled his pipe from the brown leather pouch. He thoroughly tamped the tobacco down, struck a match, puffed vigorously till the smoke started to curl upward, shook the match, then tossed it over his shoulder.

I screamed as the match, which showed no flame when it left his hand, burst into one last flicker as it flew through the air, and landed on the pile of white georgette crepe on Mama’s sewing machine.

Mama almost beat the match to the machine when she saw what was happening. But she wasn’t quick enough. “Oh, it’s burned Wilma’s dress,” she moaned. “It’s a miracle the whole thing didn’t go up in flames, but look—there are two big holes, one in the waist and one in the skirt.”

Mama held the burned dress high, spreading the full skirt. “Sister, why didn’t you put it back in the box when you set the table? You know I never leave my work out. It’s ruined, and graduation is tomorrow night. Oh, Henry, I’ve asked you dozens of times not to flip your matches!” Mama, who never cried, looked like she was ready to.

“It would’ve gone into the waste-basket like always if you hadn’t had that stuff in the way,” he answered, scowling at me.

“I knew Mama was going to finish it after supper. That’s why I didn’t bother to put it away,” I sobbed. “I didn’t think it would hurt to leave it out for a few minutes.”

Mama dug frantically through the scraps, trying to find one big enough to replace the burnt pieces. But it was expensive material and the yardage had been figured carefully. The pieces were all little ones.

“Well,” she sighed, “there’s nothing to do but buy some more goods, provided Schillings have any left, and make it over tonight. It’s lucky Mrs. Swanson bought it here in town instead of out of the catalog.”

Mama’s making Wilma’s graduation dress was just one of the neighborly things such as the women in our block just naturally did for each other. Passing the bread starter around, and trading loaves of home-made bread so several families could have fresh bread on only one was another. Helping with the children when there was a new baby or somebody sick was just routine.

Since graduation from high school was not the commonplace thing then that it is now, the whole neighborhood shared in the Swanson family’s pride in Wilma’s accomplishment. Each family in our block was helping in some way, knowing full well that with seven younger children, the Swansons couldn’t spend much on the oldest.

“We’ve got no money to give to the Swansons,” Papa objected. “Making the dress, if you want to, is one thing, but buying goods is another. You know how close run we are.”

“I should know,” Mama, who never let anything disturb her, snapped. “I’m the one who makes over clothes and cooks the cheap cuts and dried fruits and beans to keep the bills down. And I’m the one who did the work on the dress instead of buying a gift, because we’re the only ones in the neighborhood not buying something for Wilma.”

“True,” sputtered Papa, “but why should I have to pay out good money just because you want to be neighborly?”

“Remember it was your carelessness that caused the fire,” Mama called from the bedroom where she had gone to change into her street clothes. “But don’t worry, I’ll buy the goods out of my coat money that I’ve been saving from sewing. Wilma has to have her dress tomorrow.”

Papa, unperturbed, went into the front room and was immediately lost in his magazine. If the roof had come off, he wouldn’t have known it. Mama took one of the small pieces of material for a sample, got her handbag from the sideboard drawer and gave me my orders.

“Sister, you get the table cleared and the dishes done while I’m gone. I’ve not much more than time to get to the store before it closes at six.”

“Why can’t John help?” I complained, but I was talking to myself, for Mama was briskly walking out the front door and John, along with the older boys, had quietly disappeared while stuffing the last cookie into his mouth. That was the trouble being the only girl in the family. I was the one who had to help with housework.

A little breathless from hurrying, Mama was back before the dishes were done. She lost no time in changing back to her house dress before cutting into the new material. She would no more have worn dress-up clothes around the house than she would have appeared in a store wearing a house dress.

The dining table, extended by three leaves to accommodate the eight of us at mealtime, gave her plenty of working space. Her sewing machine stood in the corner. She made practically all of the boys’ clothes and all of mine, many of them hand-me-downs from my aunt who had no children of her own. Besides that, she did a lot of sewing for people better fixed than we were who could afford a sewing woman, so there weren’t many days when the machine wasn’t used.

She lost no time putting me to work with scissors, ripping the seams while she cut the new pieces. There was a lot of ripping. Snip and pull, snip and pull! It was slow going with the scissors, and her cutting was done long before I had any piece ripped apart. Then she cut the threads with a razor blade while I held the material and it didn’t take long to finish the ripping.

“It isn’t fair,” I complained as it got darker outside and I heard the other children playing their games out in the street. “I’m losing my after-supper play time. Nobody else has to stay in and work on a silly old dress.”

“You’re paying the piper,” Mama explained patiently. “Just that one little neglect of your duty was the cause of all this. Papa’s match wouldn’t have caused any damage if the dress had been put in its box.”

I didn’t know who the piper was, nor how I was paying him by working, but there were lots of Mama’s saying I didn’t understand.

“But Papa isn’t doing anything to help,” I objected. “He isn’t even having to pay for it out of his own money.

Mama smiled faintly. “We are women,” was her only comment.

Eventually the boys were called in and hustled off to bed, and still we worked. After the ripping was done, I basted and Mama stitched. On ordinary things she didn’t baste, but this was very special, so the basting was important. It was the first time she had let me work on anything nice that she was making, and a little glow of pride warmed me.

About ten she stirred up the kitchen fire and made cocoa and we had a little party, just the two of us, with cookies and cocoa. We invited Papa to join us, but he was still reading his magazine and waved us away. After we finished eating I washed and dried the dishes and put them in the cupboard while Mama did the last stitching on the blouse.

“I’m sleepy, Mama,” I said. “Can’t we finish it in the morning?”

“You know we can’t. There will be breakfast and dishes, then straightening up the front room and making beds. Wilma will want to try it on early to be sure everything fits. No, it will have to be done tonight. Now, you take the blouse and snip the basting threads every couple of inches and pull them out carefully. Don’t try pulling the whole length by the knot because it might be caught in the stitching and cause a snag. When you’re through with that, pull all the ends of the threads through to the underside and tie them neatly; then cut them off.”

She patted my shoulder and smiled. “It won’t take much longer, dear. You’ve been such a help to me. I couldn’t ever have done it without you. You may sleep a little later in the morning.

Removing the bastings wasn’t so bad, but it seemed like there would be no end to the threads to tie. Every time I thought they were all done, Mama would look it over and find some more. Some women stitched back and forth several times at the beginning and end of seams, but Mama considered that sloppy sewing.

I almost fell asleep in my chair while Mama stitched the waist and skirt together and made the placket. That done, she said, “Come on, Sister, wake up and we’ll get this done in short order. I’ve marked the places for hooks and eyes. You sew them on while I put in the hem. It’ll take me longer because the skirt is so full, but you may go to bed as soon as you’re through.”

My eyes kept closing and I stuck the needle in my fingers as often as I did the cloth, but finally finished.

Mama looked approvingly at my work. “That’s fine, dear. Now you may go to bed,” she said, “and we must be sure not to talk about this. We wouldn’t want the Swansons to know that we had been caused any inconvenience. It would make them feel bad and we don’t want anything to spoil their big day. You’ll remember that, won’t you?”

I nodded, yawing. “I’ll remember,” I promised, and stumbled toward my bedroom.

At the moment I was too sleepy even to realize what I was supposed to remember. But the next day brought the excitement of the first graduation ceremonies I had ever seen, and a secret feeling of pride that I had shared in helping make it a lovely occasion.

That long evening’s work, done so unwillingly, stands out in my memory after all these years. I remember the important feeling I had that even a little girl like myself could help to set matters right in a world where things were not always fair.

The sudden, unpredictable calamity that could follow neglect of one’s duty, however slight, was self evident at the time, as well as the necessity for teamwork in doing promptly what must be done. However, full understanding of Mama’s smiling “We are women” is something that came gradually only after years of living, loving, and learning.

"Paying the Piper by Gertrude Moore McGowan" submitted (September 2017) by her daughter, Nancy McGowan Galbraith.

Cover GOOD OLD DAYS MAGAZINE, Jan 1973

Cover GOOD OLD DAYS MAGAZINE, Jan 1973

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Gertrude Moore McGowan (1905-1992), daughter of Lulu and Harry Moore, grew up at 509 South Third Street in Victor, Colorado along with her brothers (Victor, Howard, Wallace, John, and Edward). This was the setting (perhaps about 1915) portrayed in her story titled "Paying the Piper" that was later published in the June 1973 issue of GOOD OLD DAYS MAGAZINE (when Gertrude was 68).

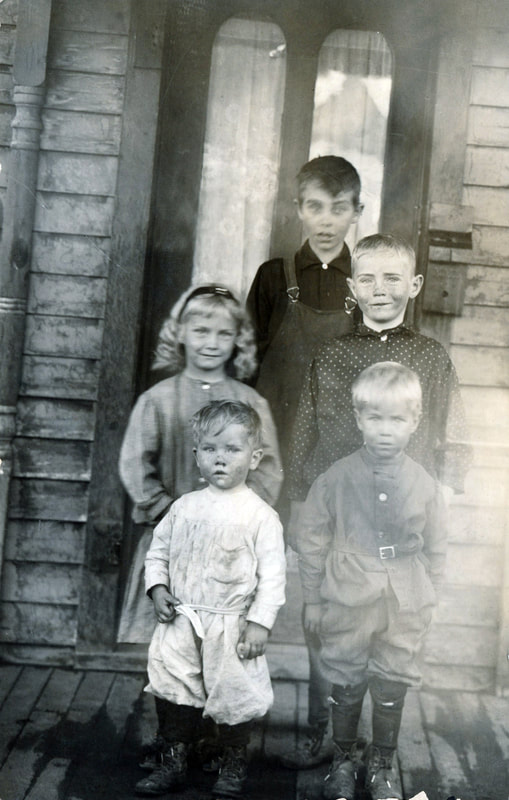

During the time portrayed in the story, Gertrude's older half-sister (Pearl) had married and was no longer living with the family, and her younger sister (Isa, born 1920) was not yet part of the family. Shown below are photos of the Moore family members depicted in Gertrude's story of "Paying the Piper" (Papa, Mama, Gertrude, John).

Gertrude Moore McGowan (1905-1992), daughter of Lulu and Harry Moore, grew up at 509 South Third Street in Victor, Colorado along with her brothers (Victor, Howard, Wallace, John, and Edward). This was the setting (perhaps about 1915) portrayed in her story titled "Paying the Piper" that was later published in the June 1973 issue of GOOD OLD DAYS MAGAZINE (when Gertrude was 68).

During the time portrayed in the story, Gertrude's older half-sister (Pearl) had married and was no longer living with the family, and her younger sister (Isa, born 1920) was not yet part of the family. Shown below are photos of the Moore family members depicted in Gertrude's story of "Paying the Piper" (Papa, Mama, Gertrude, John).

Gertrude Moore, Graduation 1923

Gertrude Moore, Graduation 1923

Click this link for “Memories Lulu Ella Manson and Harry Gordon Moore”—Gertrude Moore McGowan’s recollections about how her parents arrived in Victor in the early 1890's and coped with the challenges of raising their family during boom and bust years into the 1930's.

Gertrude Moore graduated from Victor High School in 1923. After pursuing additional education and job opportunities elsewhere, she returned to Victor to help her father in the Post Office. While working there, she met Edgar McGowan and they married in 1933. Click this link for Edgar McGowan’s “Memories of the Gold Rush Era in Victor—Those Who Struck it Rich & Lost It All.”

For the most part, Gertrude and Edgar McGowan raised their three children (Nancy, Elaine, and Donald) in Victor. Gertrude was employed as a bookkeeper at the Cresson Mine office from the late 1940s until 1956 when they moved to Wyoming. After Edgar died in 1967, Gertrude moved to California and then to Colorado Springs where she died in 1992.

Gertrude Moore graduated from Victor High School in 1923. After pursuing additional education and job opportunities elsewhere, she returned to Victor to help her father in the Post Office. While working there, she met Edgar McGowan and they married in 1933. Click this link for Edgar McGowan’s “Memories of the Gold Rush Era in Victor—Those Who Struck it Rich & Lost It All.”

For the most part, Gertrude and Edgar McGowan raised their three children (Nancy, Elaine, and Donald) in Victor. Gertrude was employed as a bookkeeper at the Cresson Mine office from the late 1940s until 1956 when they moved to Wyoming. After Edgar died in 1967, Gertrude moved to California and then to Colorado Springs where she died in 1992.

Click this link for Gertrude Moore McGowan’s Recollections About Her Family and July 4th Celebrations During Her Childhood Days in Victor.

ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTOR:

Nancy Galbraith (1935-2021) left a lasting legacy to her family and others by preserving and sharing fascinating stories about her maternal grandparents (Lulu & Harry Gordon Moore) and parents (Edgar & Gertrude Moore McGowan). According to her children, PJ & Keith, "Mom loved Victor and got a lot of enjoyment over the years sharing memories of the place where she grew up." In her honor, they commissioned a plaque that says "Nancy Ella McGowan Higgins Galbraith traveled the world, but her heart never left Victor."

ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTOR:

Nancy Galbraith (1935-2021) left a lasting legacy to her family and others by preserving and sharing fascinating stories about her maternal grandparents (Lulu & Harry Gordon Moore) and parents (Edgar & Gertrude Moore McGowan). According to her children, PJ & Keith, "Mom loved Victor and got a lot of enjoyment over the years sharing memories of the place where she grew up." In her honor, they commissioned a plaque that says "Nancy Ella McGowan Higgins Galbraith traveled the world, but her heart never left Victor."

THE PAST MATTERS. PASS IT ALONG.

The Next Generation Will Only Inherit What We Choose to Save and Make Accessible.

Please Share Your Memories and Family Connections to Victor & the World's Greatest Gold Camp

By Contacting Victor Heritage Society, PO Box 424, Victor, CO 80860 or e-mail [email protected].

The Next Generation Will Only Inherit What We Choose to Save and Make Accessible.

Please Share Your Memories and Family Connections to Victor & the World's Greatest Gold Camp

By Contacting Victor Heritage Society, PO Box 424, Victor, CO 80860 or e-mail [email protected].

VictorHeritageSociety.com

Copyright © 2023 Victor Heritage Society. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright © 2023 Victor Heritage Society. All Rights Reserved.