Mrs. Katy Bemore, long-time resident of Independence, Colorado, shared her memories on the occasion of her 80th birthday in May of 1952. Katy came to the Mining District in 1898 with her husband and four children. Since there were no homes available, they bought the engine room and hoist room of a flooded mine at Independence and made it their home. Newspaper photo by Frank Collom.

Mrs. Katy Bemore, long-time resident of Independence, Colorado, shared her memories on the occasion of her 80th birthday in May of 1952. Katy came to the Mining District in 1898 with her husband and four children. Since there were no homes available, they bought the engine room and hoist room of a flooded mine at Independence and made it their home. Newspaper photo by Frank Collom.

MEMORIES OF MRS. KATY BEMORE--Resident of Independence, CO when the train depot was blown up in 1904.

From "District Personalities--Mrs. Katy Bemore" by Helen Anderson.

Cripple Creek Gold Rush Newspaper, May 30, 1952.

When Mrs. Katy Bemore arrived in Independence [in 1898] with her husband and four children the town was thriving. Houses were springing up like mushrooms but the population was increasing so rapidly that finding a place to live became a major undertaking. When the Bemores arrived they bought the engine room and hoist room of a mine that had been abandoned when the miners struck water instead of gold. These two rooms are the center of the home in which Mrs. Bemore lives alone today, 54 years after her arrival. She celebrated her 80th birthday this month. [Article written in May 1952].

The shaft of the mine had filled with water and that forced the miners to abandon their efforts. So the shaft became a well, a more valuable addition to Independence than another mine could have been. Up to that time residents of the overpopulated area were forced to buy their water by the bucket. Many of them banded together and put a pulley and bucket over the shaft. Until the time that water was eventually piped in from Altman, residents of that portion of Independence brought their containers to the well and carried water from it. The site of the shaft is just a few yards from Mrs. Bemore’s living room window.

Three other rooms were added to the small home following the second union strike. At that time, many union miners were forced to abandon their homes and leave the District. Mr. Bemore bought the lumber from some of these homes and made the additions. The house today is cozy, handsomely furnished and extremely comfortable.

From "District Personalities--Mrs. Katy Bemore" by Helen Anderson.

Cripple Creek Gold Rush Newspaper, May 30, 1952.

When Mrs. Katy Bemore arrived in Independence [in 1898] with her husband and four children the town was thriving. Houses were springing up like mushrooms but the population was increasing so rapidly that finding a place to live became a major undertaking. When the Bemores arrived they bought the engine room and hoist room of a mine that had been abandoned when the miners struck water instead of gold. These two rooms are the center of the home in which Mrs. Bemore lives alone today, 54 years after her arrival. She celebrated her 80th birthday this month. [Article written in May 1952].

The shaft of the mine had filled with water and that forced the miners to abandon their efforts. So the shaft became a well, a more valuable addition to Independence than another mine could have been. Up to that time residents of the overpopulated area were forced to buy their water by the bucket. Many of them banded together and put a pulley and bucket over the shaft. Until the time that water was eventually piped in from Altman, residents of that portion of Independence brought their containers to the well and carried water from it. The site of the shaft is just a few yards from Mrs. Bemore’s living room window.

Three other rooms were added to the small home following the second union strike. At that time, many union miners were forced to abandon their homes and leave the District. Mr. Bemore bought the lumber from some of these homes and made the additions. The house today is cozy, handsomely furnished and extremely comfortable.

Mrs. Bemore’s four children attended school in Independence. At the time her children were attending the Independence School, which went through the eighth grade, Mrs. Bemore estimates that between 200 and 300 children were pupils there. About 10 families reside in Independence today [1952].

When the Bemores arrived in town the railroad tracks lay where the road is now. She remembers the first run of the narrow gauge. Residents raced from their homes to wave to the trainmen. It was a day of great exultation. Independence was a part of a great network of transportation.

When the Bemores arrived in town the railroad tracks lay where the road is now. She remembers the first run of the narrow gauge. Residents raced from their homes to wave to the trainmen. It was a day of great exultation. Independence was a part of a great network of transportation.

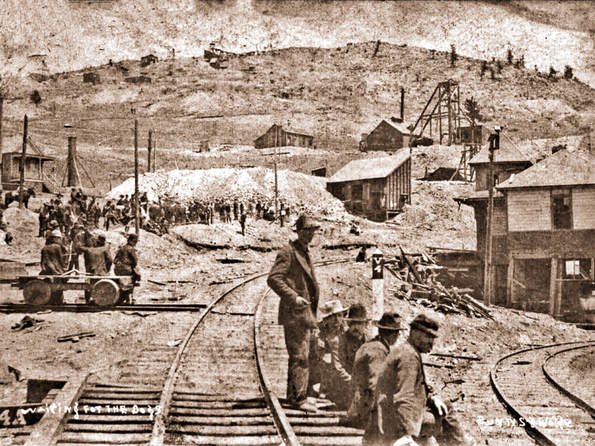

Aftermath of the explosion at the Independence Depot on June 6, 1904 resulting in the death of thirteen men.

Photo from Cripple Creek District Museum, captioned "waiting for the dogs," shared by La Jean Greeson. Click to enlarge.

Aftermath of the explosion at the Independence Depot on June 6, 1904 resulting in the death of thirteen men.

Photo from Cripple Creek District Museum, captioned "waiting for the dogs," shared by La Jean Greeson. Click to enlarge.

Explosion

At 2 a.m., one morning in 1904 when the Bemores had been asleep for several hours they were awakened by an explosion which, Mrs. Bemore asserts, lifted the bed right off the floor. “It must have been a heavy shot,” she told her husband. He recognized it for more than the usual mine blast. “It was an explosion,” he said as he dressed quickly and left the house. A great commotion followed; people were milling around and the sound of voices filled the air. By morning Mrs. Bemore had heard that the Independence Depot had been blown up as the men were coming off the night shift at the mines. Overcome with curiosity she also went to the scene of the disaster.

The vicious destruction of the depot, which was a revengeful plot during one of the bloodiest union strikes in history, has become a legendary part of the colorful history of the District. But to Mrs. Bemore the sight she viewed as she hurried to the scene of the disaster is still a ghastly nightmare, scarcely dimmed by nearly half a century. “Boots, parts of clothing and bodies lay everywhere,” she says. “There was no way to identify the dead.”

Finally after most of the town had come to view the tragedy, officials stretched a rope barrier around the scene while they began the grim job of picking up the morbid remains of 13 human beings.

At 2 a.m., one morning in 1904 when the Bemores had been asleep for several hours they were awakened by an explosion which, Mrs. Bemore asserts, lifted the bed right off the floor. “It must have been a heavy shot,” she told her husband. He recognized it for more than the usual mine blast. “It was an explosion,” he said as he dressed quickly and left the house. A great commotion followed; people were milling around and the sound of voices filled the air. By morning Mrs. Bemore had heard that the Independence Depot had been blown up as the men were coming off the night shift at the mines. Overcome with curiosity she also went to the scene of the disaster.

The vicious destruction of the depot, which was a revengeful plot during one of the bloodiest union strikes in history, has become a legendary part of the colorful history of the District. But to Mrs. Bemore the sight she viewed as she hurried to the scene of the disaster is still a ghastly nightmare, scarcely dimmed by nearly half a century. “Boots, parts of clothing and bodies lay everywhere,” she says. “There was no way to identify the dead.”

Finally after most of the town had come to view the tragedy, officials stretched a rope barrier around the scene while they began the grim job of picking up the morbid remains of 13 human beings.

Independence Depot after the explosion resulting from labor unrest in 1904. Photo shared by Rose Noal from the collections of her grandparents (Joe & Viola Madonna) and great aunt and uncle (Griff & Mollie Kate Ellis).

Independence Depot after the explosion resulting from labor unrest in 1904. Photo shared by Rose Noal from the collections of her grandparents (Joe & Viola Madonna) and great aunt and uncle (Griff & Mollie Kate Ellis).

Cage Accident

Mrs. Bemore looks back in awe at the reaction of the people in the area, herself included, to the deaths. Soon after the depot explosion another group of miners died when a cage crashed through the shaft of a mine [Vindicator]. Miners died all the time, she remembers, “we didn’t think too much about it.”

She recalls a similar difference between the days of the early 1900's and today. “When the militia moved into town, I was afraid,” she says. “I had never seen a soldier. I could watch them drill from my window and I didn’t like them.” “Today,” she smiles, “soldiers are everywhere [1952]. We LIKE them!”

Even though the early days were beset with hardship, the hope of prosperity kept the town spirited and happy. Looking out her window at the desolate country side where hundreds of homes once stood, the hillsides dotted by abandoned mines, Mrs. Bemore sighs, “If it had looked like this when I got here, I would never have stayed.”

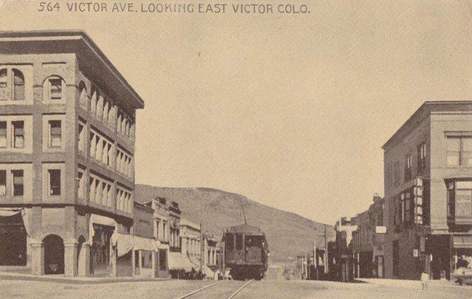

Although a street car at her door made every point in the District easily accessible, Independence was true to its name, quite independent of the other towns in the area. There were grocery stores, dry goods stores, doctors offices and a full quota of dance halls and saloons. The grocery stores came to the customer’s door in the morning, received her order and delivered the food in the evening.

Mrs. Bemore looks back in awe at the reaction of the people in the area, herself included, to the deaths. Soon after the depot explosion another group of miners died when a cage crashed through the shaft of a mine [Vindicator]. Miners died all the time, she remembers, “we didn’t think too much about it.”

She recalls a similar difference between the days of the early 1900's and today. “When the militia moved into town, I was afraid,” she says. “I had never seen a soldier. I could watch them drill from my window and I didn’t like them.” “Today,” she smiles, “soldiers are everywhere [1952]. We LIKE them!”

Even though the early days were beset with hardship, the hope of prosperity kept the town spirited and happy. Looking out her window at the desolate country side where hundreds of homes once stood, the hillsides dotted by abandoned mines, Mrs. Bemore sighs, “If it had looked like this when I got here, I would never have stayed.”

Although a street car at her door made every point in the District easily accessible, Independence was true to its name, quite independent of the other towns in the area. There were grocery stores, dry goods stores, doctors offices and a full quota of dance halls and saloons. The grocery stores came to the customer’s door in the morning, received her order and delivered the food in the evening.

There was a time when trolleys connected all the towns and most of the gold mines in the District. Mrs. Katy Bemore rode a trolley from her home in Independence to her lunch room business in Victor. Photo shared by La Jean Greeson. Click to enlarge.

There was a time when trolleys connected all the towns and most of the gold mines in the District. Mrs. Katy Bemore rode a trolley from her home in Independence to her lunch room business in Victor. Photo shared by La Jean Greeson. Click to enlarge.

Covered Wagon

The Bemores came to Colorado from Kansas. For a time they camped in a covered wagon with their children while Mr. Bemore investigated the San Luis Valley. Deciding against the valley Mr. Bemore became foreman of a cattle ranch between Olney and Manzanola. His parents who had come to Colorado with the family returned to Kansas and the Bemores settled on the ranch. Their son, Frank, was born at this time. Mrs. Bemore was happy there and felt that the job offered many opportunities since the family received a portion of the stock as part payment for the work. Mr. Bemore had heard of Cripple Creek gold, and wages as high as $3 a day, so the family came.

Mr. Bemore had several mine jobs but prosperity bypassed his family. Finally he abandoned mining and rented a lunch stand. Mrs. Bemore did the cooking. On Christmas day, 1909, he died suddenly. Mrs. Bemore continued to operate the lunch counter, using as capital the $8 which was all that was left after her husband’s death.

Mrs. Bemore is amused at the skeptical way her friends looked upon her venture. “It wasn’t considered respectable for a lady to work at night alone in a lunch counter,” she says. While operating the lunch room, she had to give up keeping boarders, which she had done for many years. At 4 o’clock in the afternoon she would gather together the food she had prepared during the day and go by streetcar to her business, returning on the last car which ran at 2:30 in the morning. She continued this schedule until her older children were self-supporting. Her younger child, Daisy, died just after her eighth grade graduation.

In the many years she had lived alone, Mrs. Bemore admits it has been lonely at times. She misses the boarders who lived in her home from time to time through the years. She finds great satisfaction in the home she kept even through the most difficult years. She finds her greatest pleasure in her granddaughter, Florence Edwards, who lives in Colorado Springs and whom she sees often.

Newspaper Article Submitted by Patrick Freeman, December 2018.

The Bemores came to Colorado from Kansas. For a time they camped in a covered wagon with their children while Mr. Bemore investigated the San Luis Valley. Deciding against the valley Mr. Bemore became foreman of a cattle ranch between Olney and Manzanola. His parents who had come to Colorado with the family returned to Kansas and the Bemores settled on the ranch. Their son, Frank, was born at this time. Mrs. Bemore was happy there and felt that the job offered many opportunities since the family received a portion of the stock as part payment for the work. Mr. Bemore had heard of Cripple Creek gold, and wages as high as $3 a day, so the family came.

Mr. Bemore had several mine jobs but prosperity bypassed his family. Finally he abandoned mining and rented a lunch stand. Mrs. Bemore did the cooking. On Christmas day, 1909, he died suddenly. Mrs. Bemore continued to operate the lunch counter, using as capital the $8 which was all that was left after her husband’s death.

Mrs. Bemore is amused at the skeptical way her friends looked upon her venture. “It wasn’t considered respectable for a lady to work at night alone in a lunch counter,” she says. While operating the lunch room, she had to give up keeping boarders, which she had done for many years. At 4 o’clock in the afternoon she would gather together the food she had prepared during the day and go by streetcar to her business, returning on the last car which ran at 2:30 in the morning. She continued this schedule until her older children were self-supporting. Her younger child, Daisy, died just after her eighth grade graduation.

In the many years she had lived alone, Mrs. Bemore admits it has been lonely at times. She misses the boarders who lived in her home from time to time through the years. She finds great satisfaction in the home she kept even through the most difficult years. She finds her greatest pleasure in her granddaughter, Florence Edwards, who lives in Colorado Springs and whom she sees often.

Newspaper Article Submitted by Patrick Freeman, December 2018.

Gravestone for Katie [Katy] Bemore at Evergreen Cemetery in Colorado Springs.

Gravestone for Katie [Katy] Bemore at Evergreen Cemetery in Colorado Springs.

ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTORS:

On May 30, 1952 when this newspaper article was published, Mrs. Katy Bemore was 80 years old and still living comfortably at her home in Independence. At that time her son, Frank Bemore, lived in Victor; her daughter, Florence Sanders, lived in Kansas City; her husband and two of her children, Harry and Daisy, had died; and her granddaughter, Florence Edwards, lived in Colorado Springs. Katy Bemore was born May 10, 1872 and died March 25, 1963 at age 90 -- over ten years after this newspaper article was published.

The newspaper clipping with this story about Mrs. Katy Bemore was saved by her son, Frank Bemore (1894-1987) and his wife Pearl (1889-1977) who lived at 309 South 5th Street in Victor. Frank worked at the Cresson and Portland mines.

When Frank Bemore passed away, his mother's story was saved by his good friend and neighbor, Patrick Freeman (who was Superintendent of the Ajax in the 1970's and once lived at 310 South 5th Street). Patrick now lives in New Mexico and recently forwarded the clipping to the Victor Heritage Society to be preserved and shared on the VHS Web Site.

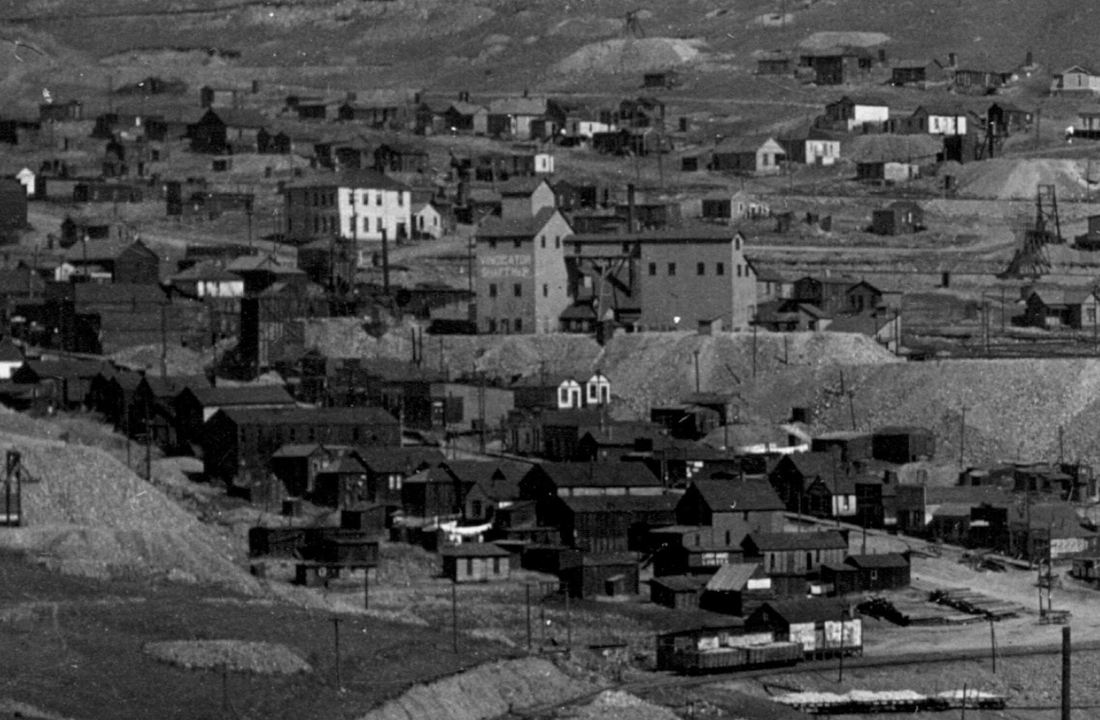

Today there is little remaining physical evidence that the town site of Independence ever existed. The homes and other structures that were once located there are all gone. Even the railroad bed that later became a county road through Independence has been obliterated by the advancement of surface mining. However, remnants of the Vindicator and several other underground mines can still be seen from a hiking trail that passes nearby.

On May 30, 1952 when this newspaper article was published, Mrs. Katy Bemore was 80 years old and still living comfortably at her home in Independence. At that time her son, Frank Bemore, lived in Victor; her daughter, Florence Sanders, lived in Kansas City; her husband and two of her children, Harry and Daisy, had died; and her granddaughter, Florence Edwards, lived in Colorado Springs. Katy Bemore was born May 10, 1872 and died March 25, 1963 at age 90 -- over ten years after this newspaper article was published.

The newspaper clipping with this story about Mrs. Katy Bemore was saved by her son, Frank Bemore (1894-1987) and his wife Pearl (1889-1977) who lived at 309 South 5th Street in Victor. Frank worked at the Cresson and Portland mines.

When Frank Bemore passed away, his mother's story was saved by his good friend and neighbor, Patrick Freeman (who was Superintendent of the Ajax in the 1970's and once lived at 310 South 5th Street). Patrick now lives in New Mexico and recently forwarded the clipping to the Victor Heritage Society to be preserved and shared on the VHS Web Site.

Today there is little remaining physical evidence that the town site of Independence ever existed. The homes and other structures that were once located there are all gone. Even the railroad bed that later became a county road through Independence has been obliterated by the advancement of surface mining. However, remnants of the Vindicator and several other underground mines can still be seen from a hiking trail that passes nearby.

THE PAST MATTERS. PASS IT ALONG.

The Next Generation Will Only Inherit What We Choose to Save and Make Accessible.

Please Share Your Memories and Family Connections to Victor & the World's Greatest Gold Camp by

Contacting Victor Heritage Society, PO Box 424, Victor, CO 80860 or e-mail [email protected].

The Next Generation Will Only Inherit What We Choose to Save and Make Accessible.

Please Share Your Memories and Family Connections to Victor & the World's Greatest Gold Camp by

Contacting Victor Heritage Society, PO Box 424, Victor, CO 80860 or e-mail [email protected].

VictorHeritageSociety.com

Copyright © 2023 Victor Heritage Society. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright © 2023 Victor Heritage Society. All Rights Reserved.