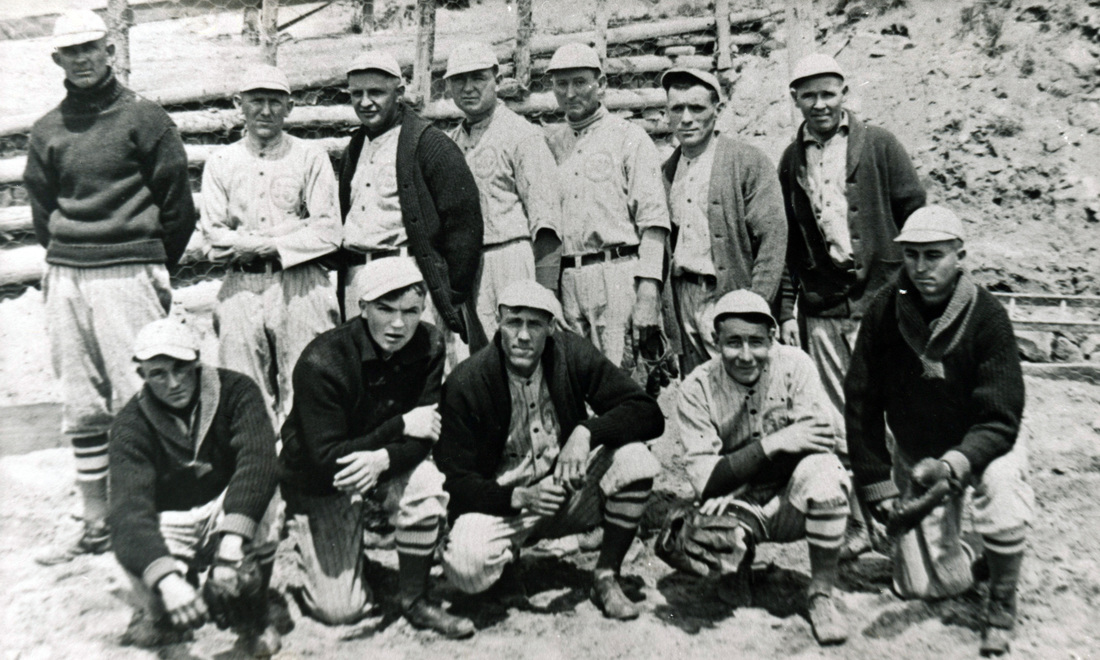

Photo courtesy of Nancy Galbraith, daughter of Edgar and Gertrude McGowan.

Photo courtesy of Nancy Galbraith, daughter of Edgar and Gertrude McGowan.

MEMORIES OF THE GOLD RUSH ERA IN VICTOR--Those Who Struck It Rich & Lost It All, Highgrading, Movie Theaters and the Opera House

By Edgar McGowan

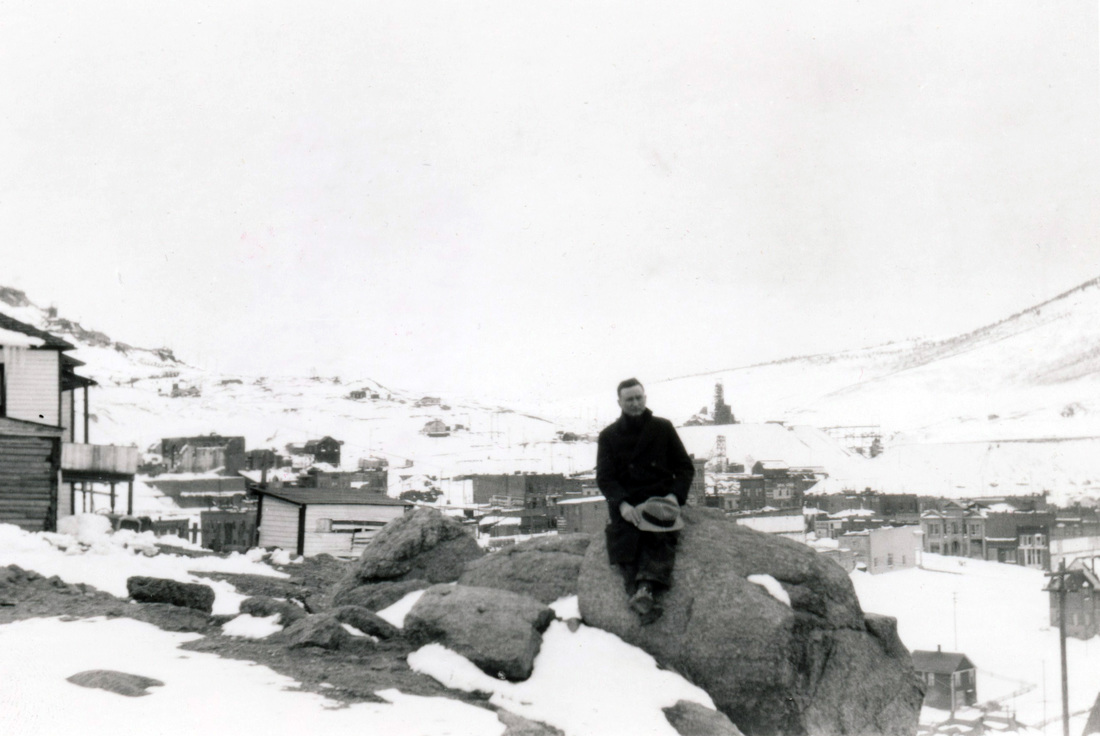

Now, let your mind go back to the “GOLD RUSH” days in the Cripple Creek-Victor District, say when I first hit there in 1907. Of course, the camp had reached its heyday some few years before that, but it still was a busy burg when I first saw it in December of 1907. I was entranced by it, for it was new to me. I felt exhilarated merely by looking at it, all covered with snow, and teeming with ever busy human beings.

By Edgar McGowan

Now, let your mind go back to the “GOLD RUSH” days in the Cripple Creek-Victor District, say when I first hit there in 1907. Of course, the camp had reached its heyday some few years before that, but it still was a busy burg when I first saw it in December of 1907. I was entranced by it, for it was new to me. I felt exhilarated merely by looking at it, all covered with snow, and teeming with ever busy human beings.

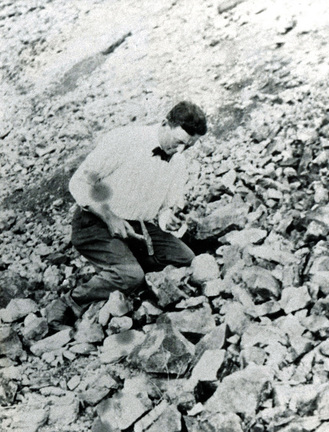

Edgar McGowan examining a rock pile in Victor--1920s or 30s. Born Dec. 5, 1884 in Grundy County, Iowa, Edgar McGowan came to Victor in 1907 when he was 23 years old. Photo courtesy of Nancy Galbraith.

Edgar McGowan examining a rock pile in Victor--1920s or 30s. Born Dec. 5, 1884 in Grundy County, Iowa, Edgar McGowan came to Victor in 1907 when he was 23 years old. Photo courtesy of Nancy Galbraith.

One of the first things I did was to get a room at a Hotel in Victor. It wasn’t an easy thing to do. So many people and such crowded conditions. There was a young fellow, about 19, who had a room. He worked from midnight to 8 o’clock the next morning at the Isabella Mill, which was situated at the northernmost rim of the District. While he was working, I slept in the room. I was out in the morning when he came to rest and sleep in the day time. We kept this up for nearly a month before I finally had a room of my own.

What became of him? He hailed from Boston, had a High School education, was well read and had studied music in a conservatory in Boston. He worked a long time, saved his money and finally married a girl in the District. They had two little girls when she, his wife, died. He raised the girls, hiring girls and women to look after the youngsters. Gertrude [my wife] has told me she used to baby sit for them when she was in Victor High. Gertrude graduated from High School in 1923. This man’s name was Harry Bennet. He finally sent the two girls to a college in Columbia, Missouri. A woman’s college the name of which I am unable to recall right now. The girls secured jobs after graduating.

Harry B. started to leasing in the mines. He finally took out about fifty thousand dollars, much of which was profit. Then he had a brain storm as so many leasers had. He decided he could make a million. So he put all the fifty thousand back into the ground, a little at a time, thinking he could and would win, but he lost it all. He worked for wages long enough to leave the District, then went to Denver and secured a job with a railroad painting crew. While painting on a bridge, he fell from the top of the steel structure and drowned in the river. What an inglorious end.

There were some queer and peculiar characters in the District in those days. There was a Lord some body from England, who was there to gain some experience in mining, besides owning a lot of mining stock, and he contracted a severe cold, then had a touch of pneumonia. He went to the Hospital and after leaving the Hospital married one of the nurses who took care of him. What became of them? They went to England where no doubt, they lived happily ever after. At least it is to be devoutly hoped.

I knew another man, an Englishman who was called a “remittance” man. He told me he was the “black sheep” of the family in dear old England. So they sent him to America and religiously and scrupulously sent him a check the first of each month. IF he would stay away. Which he did. When I first knew him, he would arise from the breakfast table when he was about half through eating, and would start off at a brisk walk and go completely around the block, then come in the dining room and resume his meal. He didn’t do that just once in awhile. He did it at every meal. When I asked him why, he told me he didn’t exactly know except that he was restless and bored with life. He was very well educated, and he and I used to discuss many things. His face had the most complete network of fine wrinkles on it that I ever saw, though he told me he was only forty years of age. I asked him why the wrinkles and he said he had lived a very dissolute life and among other things, had contracted a venereal disease. What became of him? In less than five years he went to sojourn in the State Insane Asylum in Pueblo. I knew of several men, some of whom were prominent business men, who died in the asylum from being diseased, and several committed suicide for the same reasons.

There was another Englishman, Arthur Carnduff by name, educated and belonging to a well thought of family in England, who came to try his luck at mining. For several years he mined off and on, and in the very early days of the camp, ran a mining brokerage business in Cripple Creek, though he lived in Victor. Finally he and another man secured a lease together. The other man’s name was Duncan. In a short time they made about thirty thousand dollars apiece. Then they quit leasing and started spending. Duncan gathered some of his friends together and took them to Colorado Springs—winter time—on a train. Took them to the Antlers Hotel, fed and bedded them, as the saying goes, and escorted them to the opera house to a show and a day or two later, returned them to the District. A few spludges like that, a little gambling now and then, little FRIENDLY poker games that really were more deadly than open gambling, and these men who had won big money in the leasing game, became impoverished, as their shekels trickled away from them. Duncan and his wife separated and he left the District. But Arthur Carnduff stayed and took a job as night watchman at one of the mines. He became ill and finally gave up the job. He moped around. One day he walked up to the Vindicator mine where he had been employed as watchman. He rolled a small keg out in the open where he could have been seen had anyone looked in his direction. He sat on the upended keg, took a stick of dynamite, eight inches in length and one and one quarter inches in diameter, placed a dynamite cap on the end of a short piece of fuse, pushed the cap and fuse into the stick of dynamite, lit the fuse and placed the end of the fuse that was stuck in the stick of dynamite on top of his head, covering it with his hat. He calmly waited and soon, puff, there was a headless corpse. One day a letter came from a brother of his in England. Arthur Carnduff had writ to his family, his parents and brothers and sisters, he was not married, and had told them he was about to give up and end everything. His fellow Lodge members in Victor had cabled the family in England of Carnduff’s death. The brother in England had sort of berated the friends of Carnduff in Victor for not having notified the family of Carnduff’s financial condition, saying they would gladly have helped him. But Carnduff’s friends had thought he had enough money left over from his leasing to tide him along. Carnduff was too proud to ask for help. Many more I could tell you about.

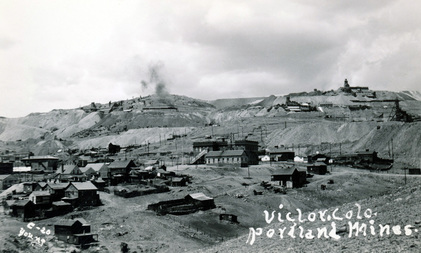

At the time I first arrived in Victor, when the snow had melted, which was about the first of June, the hills would be dotted with men carrying picks and shovels and small canvass sacks in which to take to the assayers samples of the rock and dirt they would dig up, hoping this would be “pay dirt”. Occasionally, it was, but not often.

Gold is where you find it, and it is very hard to find. That is an old saying, but a true one.

At the time I was first there, and for a number of years after about twelve or fifteen men, on an average each year, would make a fortune leasing. All the way from fifty to a hundred thousand dollars, and nearly every one of them gambled and drank it up. Just a few, a very few, saved their money and left.

What became of him? He hailed from Boston, had a High School education, was well read and had studied music in a conservatory in Boston. He worked a long time, saved his money and finally married a girl in the District. They had two little girls when she, his wife, died. He raised the girls, hiring girls and women to look after the youngsters. Gertrude [my wife] has told me she used to baby sit for them when she was in Victor High. Gertrude graduated from High School in 1923. This man’s name was Harry Bennet. He finally sent the two girls to a college in Columbia, Missouri. A woman’s college the name of which I am unable to recall right now. The girls secured jobs after graduating.

Harry B. started to leasing in the mines. He finally took out about fifty thousand dollars, much of which was profit. Then he had a brain storm as so many leasers had. He decided he could make a million. So he put all the fifty thousand back into the ground, a little at a time, thinking he could and would win, but he lost it all. He worked for wages long enough to leave the District, then went to Denver and secured a job with a railroad painting crew. While painting on a bridge, he fell from the top of the steel structure and drowned in the river. What an inglorious end.

There were some queer and peculiar characters in the District in those days. There was a Lord some body from England, who was there to gain some experience in mining, besides owning a lot of mining stock, and he contracted a severe cold, then had a touch of pneumonia. He went to the Hospital and after leaving the Hospital married one of the nurses who took care of him. What became of them? They went to England where no doubt, they lived happily ever after. At least it is to be devoutly hoped.

I knew another man, an Englishman who was called a “remittance” man. He told me he was the “black sheep” of the family in dear old England. So they sent him to America and religiously and scrupulously sent him a check the first of each month. IF he would stay away. Which he did. When I first knew him, he would arise from the breakfast table when he was about half through eating, and would start off at a brisk walk and go completely around the block, then come in the dining room and resume his meal. He didn’t do that just once in awhile. He did it at every meal. When I asked him why, he told me he didn’t exactly know except that he was restless and bored with life. He was very well educated, and he and I used to discuss many things. His face had the most complete network of fine wrinkles on it that I ever saw, though he told me he was only forty years of age. I asked him why the wrinkles and he said he had lived a very dissolute life and among other things, had contracted a venereal disease. What became of him? In less than five years he went to sojourn in the State Insane Asylum in Pueblo. I knew of several men, some of whom were prominent business men, who died in the asylum from being diseased, and several committed suicide for the same reasons.

There was another Englishman, Arthur Carnduff by name, educated and belonging to a well thought of family in England, who came to try his luck at mining. For several years he mined off and on, and in the very early days of the camp, ran a mining brokerage business in Cripple Creek, though he lived in Victor. Finally he and another man secured a lease together. The other man’s name was Duncan. In a short time they made about thirty thousand dollars apiece. Then they quit leasing and started spending. Duncan gathered some of his friends together and took them to Colorado Springs—winter time—on a train. Took them to the Antlers Hotel, fed and bedded them, as the saying goes, and escorted them to the opera house to a show and a day or two later, returned them to the District. A few spludges like that, a little gambling now and then, little FRIENDLY poker games that really were more deadly than open gambling, and these men who had won big money in the leasing game, became impoverished, as their shekels trickled away from them. Duncan and his wife separated and he left the District. But Arthur Carnduff stayed and took a job as night watchman at one of the mines. He became ill and finally gave up the job. He moped around. One day he walked up to the Vindicator mine where he had been employed as watchman. He rolled a small keg out in the open where he could have been seen had anyone looked in his direction. He sat on the upended keg, took a stick of dynamite, eight inches in length and one and one quarter inches in diameter, placed a dynamite cap on the end of a short piece of fuse, pushed the cap and fuse into the stick of dynamite, lit the fuse and placed the end of the fuse that was stuck in the stick of dynamite on top of his head, covering it with his hat. He calmly waited and soon, puff, there was a headless corpse. One day a letter came from a brother of his in England. Arthur Carnduff had writ to his family, his parents and brothers and sisters, he was not married, and had told them he was about to give up and end everything. His fellow Lodge members in Victor had cabled the family in England of Carnduff’s death. The brother in England had sort of berated the friends of Carnduff in Victor for not having notified the family of Carnduff’s financial condition, saying they would gladly have helped him. But Carnduff’s friends had thought he had enough money left over from his leasing to tide him along. Carnduff was too proud to ask for help. Many more I could tell you about.

At the time I first arrived in Victor, when the snow had melted, which was about the first of June, the hills would be dotted with men carrying picks and shovels and small canvass sacks in which to take to the assayers samples of the rock and dirt they would dig up, hoping this would be “pay dirt”. Occasionally, it was, but not often.

Gold is where you find it, and it is very hard to find. That is an old saying, but a true one.

At the time I was first there, and for a number of years after about twelve or fifteen men, on an average each year, would make a fortune leasing. All the way from fifty to a hundred thousand dollars, and nearly every one of them gambled and drank it up. Just a few, a very few, saved their money and left.

I so well remember one man who had come from Sweden. He was not married and for about six or seven years he worked as a machine man at four dollars a day. He finally had six thousand dollars saved up. He set the day for quitting and returning to Sweden, but that very day when he came up out of the mine, he stepped out and tripped and fell down the shaft to his death. What a terrible disappointment. Several similar incidents took place.

There was a lot of “HIGH GRADING” going on, up until about 1913. In case you do not know what “high grading” is, it was where the men who worked and even some of whom did not work, would steal some of the rich ore they mined and sell it to assayers for a small fraction of what it was worth. The men made big money out of the deals because the ore was so rich, running from a dollar to eighty dollars a pound. However, the assayers were the ones who made the most money.

The biggest part of the highgrading took place prior to 1913. In that year the U.S. Government levied a production tax, similar to the income tax. It was one percent instead of the high levies we have to pay now. Many highgraders and assayers were arrested in the District, some of them being sent to a federal prison at Leavenworth, Kansas. That sort of stopped much of the highgrading, but not all of it. A million dollars a year was being stolen in the Cripple Creek and Victor mines by highgraders and it no doubt was a good thing it finally was stopped.

There was a lot of “HIGH GRADING” going on, up until about 1913. In case you do not know what “high grading” is, it was where the men who worked and even some of whom did not work, would steal some of the rich ore they mined and sell it to assayers for a small fraction of what it was worth. The men made big money out of the deals because the ore was so rich, running from a dollar to eighty dollars a pound. However, the assayers were the ones who made the most money.

The biggest part of the highgrading took place prior to 1913. In that year the U.S. Government levied a production tax, similar to the income tax. It was one percent instead of the high levies we have to pay now. Many highgraders and assayers were arrested in the District, some of them being sent to a federal prison at Leavenworth, Kansas. That sort of stopped much of the highgrading, but not all of it. A million dollars a year was being stolen in the Cripple Creek and Victor mines by highgraders and it no doubt was a good thing it finally was stopped.

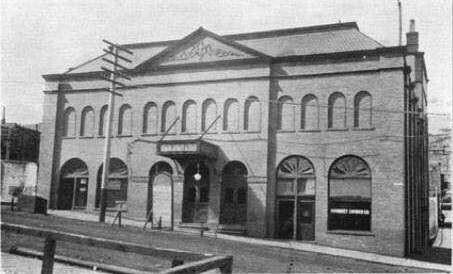

Victor Opera House-- Photo courtesy of LaJean Greeson.

Victor Opera House-- Photo courtesy of LaJean Greeson.

I wrote an article on highgrading and it was published in the Cripple Creek “GOLD RUSH” paper. Along in the early fifties, there was a barber in Victor, who had not been there very long before this article was published, and he did not believe it when he read it. He said to me, “Mac, how come you made up such a bunch of lies about highgrading? You don’t expect anybody to believe them, do you?” To which I replied, “Ask Mr. A.W.Oliver, who came to Victor in the early 1890’s and who had lived here ever since.” He did and Mr. Oliver told him every word I had written was true as could be, that he himself knew of the truth of what I had written.

In 1907 when I first went to Victor, there were three picture shows there and they were all crowded every afternoon and night. Many of the miners worked night shifts and could go only in the afternoons. There were three shifts of workers in most of the mines, three shifts each twenty-four hours: from eight o’clock in the morning to four in the afternoon, from four in the afternoon until twelve at night, from twelve at night until eight in the morning. Later on, they worked two shifts, from eight in the morning until four-thirty in the afternoon, and from six o’clock in the evening until two-thirty the next morning. The streets were so crowded at night, and I mean until past midnight, that if you wanted to walk down or up the streets, lots of hilly streets, you would need to walk out in the middle of the street if you were in a hurry to get any place.

There was an immense opera house in Victor, said to be the biggest west of Chicago when it was built, it burned in about 1920. The big shows at that time running in New York would send their cast to Chicago, St. Louis, Kansas City, and Denver on their way to the west coast. And most of them made one night stands in Victor at the opera house. The cast would come from Colorado Springs on the afternoon train, play that night and leave early the next morning. Of course it was on a vaudeville circuit, also.

In 1907 when I first went to Victor, there were three picture shows there and they were all crowded every afternoon and night. Many of the miners worked night shifts and could go only in the afternoons. There were three shifts of workers in most of the mines, three shifts each twenty-four hours: from eight o’clock in the morning to four in the afternoon, from four in the afternoon until twelve at night, from twelve at night until eight in the morning. Later on, they worked two shifts, from eight in the morning until four-thirty in the afternoon, and from six o’clock in the evening until two-thirty the next morning. The streets were so crowded at night, and I mean until past midnight, that if you wanted to walk down or up the streets, lots of hilly streets, you would need to walk out in the middle of the street if you were in a hurry to get any place.

There was an immense opera house in Victor, said to be the biggest west of Chicago when it was built, it burned in about 1920. The big shows at that time running in New York would send their cast to Chicago, St. Louis, Kansas City, and Denver on their way to the west coast. And most of them made one night stands in Victor at the opera house. The cast would come from Colorado Springs on the afternoon train, play that night and leave early the next morning. Of course it was on a vaudeville circuit, also.

"Memories of the Gold Rush Era in Victor--Those Who Struck It Rich & Lost It All, Highgrading, Movie Theaters & the Opera House by Edgar McGowan" submitted (July 2016) by daughter, Nancy McGowan Galbraith.

Edgar McGowan and his one year old daughter, Nancy, 1936.

Edgar McGowan and his one year old daughter, Nancy, 1936.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Edgar McGowan's Memories of the Gold Rush Era in Victor were excerpted from a letter he wrote from Riverton, Wyoming on March 31, 1961 to his cousin, Addie.

The letter and accompanying photographs were submitted in July 2016 by Nancy McGowan Galbraith (daughter of Edgar McGowan and Gertrude Moore) who lived in Virginia Beach, Virginia at the time.

Edgar McGowan was born in 1884 in Grundy County Iowa. He came to Victor, Colorado in 1907 where he met and married Gertrude Moore in 1933. Edgar and Gertrude had three children--Nancy, Elaine, and Donald. They opened a wallpaper store in Victor, but briefly moved away and then returned several times in search of better employment opportunities. In 1956, they moved to Riverton, Wyoming where Edgar died in 1967. His wife, Gertrude, subsequently moved to California and then to Colorado Springs where she died in 1992

Edgar McGowan's Memories of the Gold Rush Era in Victor were excerpted from a letter he wrote from Riverton, Wyoming on March 31, 1961 to his cousin, Addie.

The letter and accompanying photographs were submitted in July 2016 by Nancy McGowan Galbraith (daughter of Edgar McGowan and Gertrude Moore) who lived in Virginia Beach, Virginia at the time.

Edgar McGowan was born in 1884 in Grundy County Iowa. He came to Victor, Colorado in 1907 where he met and married Gertrude Moore in 1933. Edgar and Gertrude had three children--Nancy, Elaine, and Donald. They opened a wallpaper store in Victor, but briefly moved away and then returned several times in search of better employment opportunities. In 1956, they moved to Riverton, Wyoming where Edgar died in 1967. His wife, Gertrude, subsequently moved to California and then to Colorado Springs where she died in 1992

Other stories contributed by Nancy McGowan Galbriath:

- Memories of Lulu Ella Manson & Harry Gordon Moore as Recalled in Letters Written by Gertrude Moore McGowan (daughter).

- Gold Camp Celebration: Fourth of July in Victor, Early 1900’s. Childhood Memories Recalled by Gertrude Moore McGowan (daughter of Lulu & Harry Gordon Moore).

- Paying The Piper: Childhood Memories and Lessons Learn Growing Up in Victor, Colorado in the Early 1900’s by Gertrude Moore McGowan (daughter of Lulu & Harry Gordon Moore).

ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTOR:

Nancy Galbraith (1935-2021) left a lasting legacy to her family and others by preserving and sharing fascinating stories about her maternal grandparents (Lulu & Harry Gordon Moore) and parents (Edgar & Gertrude Moore McGowan). According to her children, PJ & Keith, "Mom loved Victor and got a lot of enjoyment over the years sharing memories of the place where she grew up." In her honor, they commissioned a plaque that says "Nancy Ella McGowan Higgins Galbraith traveled the world, but her heart never left Victor."

Nancy Galbraith (1935-2021) left a lasting legacy to her family and others by preserving and sharing fascinating stories about her maternal grandparents (Lulu & Harry Gordon Moore) and parents (Edgar & Gertrude Moore McGowan). According to her children, PJ & Keith, "Mom loved Victor and got a lot of enjoyment over the years sharing memories of the place where she grew up." In her honor, they commissioned a plaque that says "Nancy Ella McGowan Higgins Galbraith traveled the world, but her heart never left Victor."

THE PAST MATTERS. PASS IT ALONG.

The Next Generation Will Only Inherit What We Choose to Save and Make Accessible.

Please Share Your Memories and Family Connections to Victor & the World's Greatest Gold Camp by

Contacting Victor Heritage Society, PO Box 424, Victor, CO 80860 or e-mail [email protected].

The Next Generation Will Only Inherit What We Choose to Save and Make Accessible.

Please Share Your Memories and Family Connections to Victor & the World's Greatest Gold Camp by

Contacting Victor Heritage Society, PO Box 424, Victor, CO 80860 or e-mail [email protected].

VictorHeritageSociety.com

Copyright © 2023 Victor Heritage Society. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright © 2023 Victor Heritage Society. All Rights Reserved.