WORKING UNDERGROUND IN THE CRIPPLE CREEK & VICTOR MINING DISTRICT (1972 to 1979): How I Got the Shaft, the Gas, and the Broken Steel. By Randall Stewart.

My first underground mining experience happened in the summer of 1970 in Nevada while working with three geologists who were employed by Golden Cycle – Jim Hill, Jack Hamm and John Hague. Much of that summer I was in Mill Canyon, Nevada, with Jack Hamm. We were surveying, mapping and sampling an old underground mine to determine whether or not the potential for future gold development was there. We were not equipped with electricity, so we used acetylene lamps to be able to see underground. You put calcium carbide (CaC2) and water in the lamp in separate compartments, and the water dripped down on the calcium carbide producing acetylene gas (C2H2). When you lit the gas, it made a pretty good light that reflected off the curved mirror surface of the lamp – projecting the light forward. We did this for many weeks that summer until we surveyed, mapped and sampled the entire mine workings.

My first experience in the Cripple Creek-Victor area was in the summer of 1972. I spent part of that summer doing sample prep down in Colorado Springs for Dave Long – the assayer for Golden Cycle. The second half of the summer I was on a survey crew doing surface work up in Cripple Creek and Victor. We worked out of the old Carlton Mill.

My first underground mining experience happened in the summer of 1970 in Nevada while working with three geologists who were employed by Golden Cycle – Jim Hill, Jack Hamm and John Hague. Much of that summer I was in Mill Canyon, Nevada, with Jack Hamm. We were surveying, mapping and sampling an old underground mine to determine whether or not the potential for future gold development was there. We were not equipped with electricity, so we used acetylene lamps to be able to see underground. You put calcium carbide (CaC2) and water in the lamp in separate compartments, and the water dripped down on the calcium carbide producing acetylene gas (C2H2). When you lit the gas, it made a pretty good light that reflected off the curved mirror surface of the lamp – projecting the light forward. We did this for many weeks that summer until we surveyed, mapped and sampled the entire mine workings.

My first experience in the Cripple Creek-Victor area was in the summer of 1972. I spent part of that summer doing sample prep down in Colorado Springs for Dave Long – the assayer for Golden Cycle. The second half of the summer I was on a survey crew doing surface work up in Cripple Creek and Victor. We worked out of the old Carlton Mill.

Headframe towering over the shaft of the Ajax Mine. Photo from Randall Stewart, 2018.

Headframe towering over the shaft of the Ajax Mine. Photo from Randall Stewart, 2018.

Inspecting Timber in the Ajax Mine Shaft

On the last day of work that summer, before I would return to school in Pueblo where I was working on a degree in geology, the survey crew went up to the Ajax mine. I met Louis Yturbe, the shift boss up there, and Pat Freeman, the mine superintendent.

They were looking for a volunteer to go down the Ajax shaft and inspect the timber. They were trying to find out what condition the timber of the shaft was in – and what might have to be done to allow a skip to move freely in the shaft. The manway was out of service due to cave-ins and rotten timber, so the shaft had to be used for the inspection. In hind sight, what I did next was very stupid – but I volunteered, and they accepted.

This time I had an electric lamp I could strap around my waist and a good light source I could put in my hardhat. Now this was before there was such a thing as Mine Safety and Health Administration.

They had a flatbed pickup truck rigged with a winch and a steel wire rope run through a high A-frame extension above and out the back end of the truck. Attached to the end of the wire rope was a wooden platform – a little longer than the size of my butt – but only about 6 inches wide. The plan was to lower me down the shaft slowly and my job was to inspect the timber in place and be able to tell them what shape it was in when they brought me back up. They wanted to send me down the entire length of wire rope so that I could inspect several hundred feet of timber. Because they would not be able to hear me, the plan also included a way to safeguard me during the descent. If I needed them to stop the winch, reverse it and bring me back to the surface, I was to wave my headlamp furiously so that the men on the surface would know I was in trouble. The fact that the Ajax was 3100 feet deep did not really seem to bother me – like I said, I was stupid.

As I was lowered into the shaft, daylight disappearing more rapidly than I had expected, I carefully examined the timber in the compartment on all four sides. The chair I was in sort of naturally spun around as the cable unwound from the winch. I was focused completely on the timber, and did notice several pieces of wood missing as I descended. I did not notice the piece of timber that was laying crossways in the shaft. My first awareness of it was when the knees of both legs got caught on it – and the chair continued to drop down. I immediately grabbed my headlamp and began waving it frantically trying to get the attention of the observers on the surface. The chair continued to descend. At some point, the chair dropped down far enough so that I could straighten out my legs. At just about the point where my ankles were going to drop off the timber – and I was going to have to make sure I landed back in the seat, the chair suddenly stopped. I hung there for a moment with head pointed down the shaft, my hands grasping both wires on either side of the wooden plank, my headlamp dangling from my hardhat, and my ankles still hooked on the timber. Then the chair began to rise. I felt better. At the right time, I swung neatly back onto the seat, my legs came off the timber in the shaft, and I was on my way back to the surface.

When I cracked the surface, I did not dare show my fear. These were mining men. I calmly explained to them what had happened, that many pieces of timber that should be there were actually missing, and the timber was soaking wet and rotten in many places. I was told that I had been lowered down to a depth of around 150 feet before being pulled out. I have the distinction of being the first man down the Ajax shaft to that depth since the mine’s closure in 1961.

Before I graduated with my degree in Geology from Southern Colorado State College in Pueblo, I was notified by Golden Cycle that I had a job with them as a mining geologist when I finished school. I think that some of the men involved with the shaft incident were feeling a little guilty – so that worked in my favor. My friend from school did not have a job when he graduated, but I told him that I could get him on at Golden Cycle. And I did. So that is how Cleo Alan Tapp was hired by the Golden Cycle operation in Cripple, later to be taken over by Texas Gulf.

I went to work as a geologist for Golden Cycle Mining Corporation in June, 1973. By this time, much of the shaft providing access to the upper workings of the Ajax had been re-timbered. They had removed the old timber and replaced it with new timber. They had ‘hung’ the timber, starting from the collar and worked their way downward – allowing men to get to the upper levels first. At this point, D. B. Smith was the General Manager of Golden Cycle’s Cripple Creek/Victor operations. While riding in a vehicle one day with D.B. and others, he asked me how much I weighed. I told him about 135 pounds. He replied that he had bowel movements bigger than that. Not sure what old D.B. was getting at on this one.

On the last day of work that summer, before I would return to school in Pueblo where I was working on a degree in geology, the survey crew went up to the Ajax mine. I met Louis Yturbe, the shift boss up there, and Pat Freeman, the mine superintendent.

They were looking for a volunteer to go down the Ajax shaft and inspect the timber. They were trying to find out what condition the timber of the shaft was in – and what might have to be done to allow a skip to move freely in the shaft. The manway was out of service due to cave-ins and rotten timber, so the shaft had to be used for the inspection. In hind sight, what I did next was very stupid – but I volunteered, and they accepted.

This time I had an electric lamp I could strap around my waist and a good light source I could put in my hardhat. Now this was before there was such a thing as Mine Safety and Health Administration.

They had a flatbed pickup truck rigged with a winch and a steel wire rope run through a high A-frame extension above and out the back end of the truck. Attached to the end of the wire rope was a wooden platform – a little longer than the size of my butt – but only about 6 inches wide. The plan was to lower me down the shaft slowly and my job was to inspect the timber in place and be able to tell them what shape it was in when they brought me back up. They wanted to send me down the entire length of wire rope so that I could inspect several hundred feet of timber. Because they would not be able to hear me, the plan also included a way to safeguard me during the descent. If I needed them to stop the winch, reverse it and bring me back to the surface, I was to wave my headlamp furiously so that the men on the surface would know I was in trouble. The fact that the Ajax was 3100 feet deep did not really seem to bother me – like I said, I was stupid.

As I was lowered into the shaft, daylight disappearing more rapidly than I had expected, I carefully examined the timber in the compartment on all four sides. The chair I was in sort of naturally spun around as the cable unwound from the winch. I was focused completely on the timber, and did notice several pieces of wood missing as I descended. I did not notice the piece of timber that was laying crossways in the shaft. My first awareness of it was when the knees of both legs got caught on it – and the chair continued to drop down. I immediately grabbed my headlamp and began waving it frantically trying to get the attention of the observers on the surface. The chair continued to descend. At some point, the chair dropped down far enough so that I could straighten out my legs. At just about the point where my ankles were going to drop off the timber – and I was going to have to make sure I landed back in the seat, the chair suddenly stopped. I hung there for a moment with head pointed down the shaft, my hands grasping both wires on either side of the wooden plank, my headlamp dangling from my hardhat, and my ankles still hooked on the timber. Then the chair began to rise. I felt better. At the right time, I swung neatly back onto the seat, my legs came off the timber in the shaft, and I was on my way back to the surface.

When I cracked the surface, I did not dare show my fear. These were mining men. I calmly explained to them what had happened, that many pieces of timber that should be there were actually missing, and the timber was soaking wet and rotten in many places. I was told that I had been lowered down to a depth of around 150 feet before being pulled out. I have the distinction of being the first man down the Ajax shaft to that depth since the mine’s closure in 1961.

Before I graduated with my degree in Geology from Southern Colorado State College in Pueblo, I was notified by Golden Cycle that I had a job with them as a mining geologist when I finished school. I think that some of the men involved with the shaft incident were feeling a little guilty – so that worked in my favor. My friend from school did not have a job when he graduated, but I told him that I could get him on at Golden Cycle. And I did. So that is how Cleo Alan Tapp was hired by the Golden Cycle operation in Cripple, later to be taken over by Texas Gulf.

I went to work as a geologist for Golden Cycle Mining Corporation in June, 1973. By this time, much of the shaft providing access to the upper workings of the Ajax had been re-timbered. They had removed the old timber and replaced it with new timber. They had ‘hung’ the timber, starting from the collar and worked their way downward – allowing men to get to the upper levels first. At this point, D. B. Smith was the General Manager of Golden Cycle’s Cripple Creek/Victor operations. While riding in a vehicle one day with D.B. and others, he asked me how much I weighed. I told him about 135 pounds. He replied that he had bowel movements bigger than that. Not sure what old D.B. was getting at on this one.

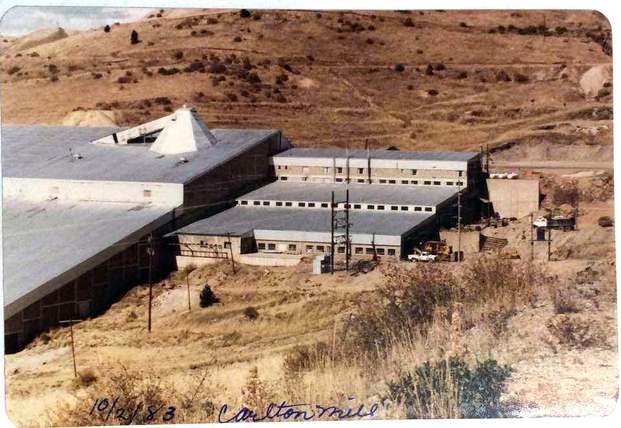

Carlton Mill, now dismantled the site is covered by an enormous leach pad.

Photo contributed by La Jean Greeson.

Carlton Mill, now dismantled the site is covered by an enormous leach pad.

Photo contributed by La Jean Greeson.

We worked out of the Carlton Mill. My first job was to log core taken from diamond drill holes located at the surface near the old Carbonate Mine. We were trying to find the extension of the Bobtail vein, the Newmarket vein and the X-10-U-8 vein from the Ajax near the surface so that we could access any ore we found from the upper levels of the Ajax by driving new drift over there. In 1973, the price of gold was around $60/ounce on the free market, so we had to find some pretty high grade stuff to make the project work – not much luck as I recall.

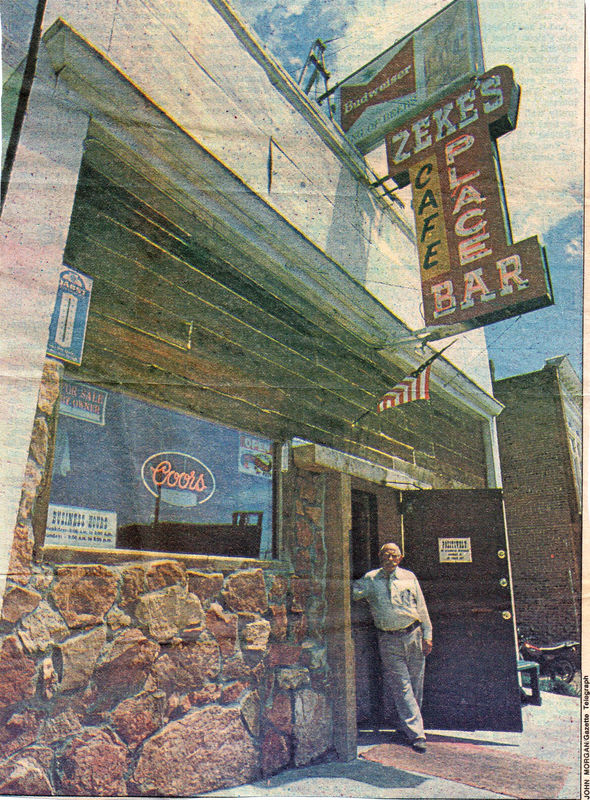

Ohrt Yeager ran Zeke's Place Cafe & Bar on South Third Street where Shorty Bielz played the guitar and sang while Gene Leaf was the drummer. Photo contributed by La Jean Greeson.

Ohrt Yeager ran Zeke's Place Cafe & Bar on South Third Street where Shorty Bielz played the guitar and sang while Gene Leaf was the drummer. Photo contributed by La Jean Greeson.

I would retrieve core from the drill rigs and bring it back to the mill for logging. I worked downstairs near the assay lab. That is where I renewed my acquaintance with Gene Leaf, who was working sample prep – some of which was my logged and split core. Gene worked for Dave Long. Gene and I knew each other from Southern Colorado State College and became pretty good friends. I used to love to watch him and Shorty Bielz play at Zeke’s Place in Victor on the weekends. Gene was drummer and Shorty was guitar man and singer. Shorty knew three chords, but did a fair rendition of ‘Kansas City’. I bet I heard that song by Gene and Shorty a hundred times or more over the years.

Before the summer was over, I joined the Victor Elks Club (Lodge #367) – on the advice of Jack, Pat and D.B. Toward the end of that summer, there was a party up at old 367 to celebrate the career of the 3 Golden Cycle geologists I had worked with in Nevada – Jack Hamm, Jim Hill, and John Hague. They were going their separate ways. John Hague arrived with his beautiful red-headed wife – wearing high heeled shoes and a great dress – and I struggled to take my eyes off of her. After a while, I got the opportunity to talk to her and reminded her that I met her once before in Nevada. She looked at me and told me that she had never been to Nevada in her life, and that I must be mistaken. By now, Smith, Freeman, Yturbe, Hill, Hamm and Hague were all staring at me. The room had dropped into silence. I guess I said to her that I was pretty sure I had seen her in Nevada. She looked at Hague pretty hard and asked me to dance. After a while, Freeman pulled me aside and asked me how stupid I was – he wanted to know if I didn’t realize that Hague and his wife had just gotten back together after years of trouble and separation. Pat tried to tell me that what had happened was my fault. I did not accept responsibility for the unfortunate event then – and I do not accept it now. But I was involved. If I had been able to ignore the woman, the whole thing would not have happened. I have always had trouble ignoring attractive women.

Sometime that early winter of 1973, Gene and I took an artist friend of mine, Jim Selbe, down to Colorado Springs, where he was going to meet a girlfriend – and did not need a ride back up to Cripple Creek and Victor by us. Gene was driving an old pickup truck and there were some adult beverages involved. When he and I started back up the hill, it started to snow. By the time we reached Manitou Springs, it was snowing heavily and the roads were covered – and slippery. We went on up the hill into the canyon above Manitou, when a cop dropped in behind us and turned on his lights, wanting us to pull over. Gene and I looked at each other, we looked at the open beer cans we each had, and he asked if we should go for it. I told him sure. So he stepped on it and the pickup started to leave the cop behind. That cop was fishtailing and sliding all over the highway, and pretty quickly gave up the chase. He must not have ever gotten close enough to us to get the license plate number, because as far as I know, Gene never suffered any consequences.

In 1973, there was not a lot of activity going on after work in Victor, except at the Elks Club, Lil’s place, and Zeke’s place. So sometimes I would venture over to Cripple Creek. One night, I went into the Cottage Inn – a place where I came to see my face on the bar room floor more than once to compliment the beautiful lady’s face that was actually imbedded in the Cottage floor. I ran into a rough crowd that night – I believe it included Billy Shoe, Ogre, Charlie Nutall and various other characters of the time. They were all Cripple Creekers and told me that they really didn’t like people from Victor coming into their bar and messing things up. We danced around the room a little bit, but these men were, for the most part, larger than me and I slowly realized that I could take a pretty good beating if I did not do what they wanted me to do. So I laid my head, very long hair and all, on the bar and got doused with a pitcher of beer – baptized so to speak. After that, there appears to have been peace in the valley. Until the constabulary showed up to make sure we all left when the bar closed. My recollection is a bit fuzzy on this, but I think some of the Cripple Creek boys started shoving the deputy around a bit, eventually taking his gun and playing catch with it in Bennett Avenue. I left pretty quickly at that point, so I am not sure how that episode ended.

Before the summer was over, I joined the Victor Elks Club (Lodge #367) – on the advice of Jack, Pat and D.B. Toward the end of that summer, there was a party up at old 367 to celebrate the career of the 3 Golden Cycle geologists I had worked with in Nevada – Jack Hamm, Jim Hill, and John Hague. They were going their separate ways. John Hague arrived with his beautiful red-headed wife – wearing high heeled shoes and a great dress – and I struggled to take my eyes off of her. After a while, I got the opportunity to talk to her and reminded her that I met her once before in Nevada. She looked at me and told me that she had never been to Nevada in her life, and that I must be mistaken. By now, Smith, Freeman, Yturbe, Hill, Hamm and Hague were all staring at me. The room had dropped into silence. I guess I said to her that I was pretty sure I had seen her in Nevada. She looked at Hague pretty hard and asked me to dance. After a while, Freeman pulled me aside and asked me how stupid I was – he wanted to know if I didn’t realize that Hague and his wife had just gotten back together after years of trouble and separation. Pat tried to tell me that what had happened was my fault. I did not accept responsibility for the unfortunate event then – and I do not accept it now. But I was involved. If I had been able to ignore the woman, the whole thing would not have happened. I have always had trouble ignoring attractive women.

Sometime that early winter of 1973, Gene and I took an artist friend of mine, Jim Selbe, down to Colorado Springs, where he was going to meet a girlfriend – and did not need a ride back up to Cripple Creek and Victor by us. Gene was driving an old pickup truck and there were some adult beverages involved. When he and I started back up the hill, it started to snow. By the time we reached Manitou Springs, it was snowing heavily and the roads were covered – and slippery. We went on up the hill into the canyon above Manitou, when a cop dropped in behind us and turned on his lights, wanting us to pull over. Gene and I looked at each other, we looked at the open beer cans we each had, and he asked if we should go for it. I told him sure. So he stepped on it and the pickup started to leave the cop behind. That cop was fishtailing and sliding all over the highway, and pretty quickly gave up the chase. He must not have ever gotten close enough to us to get the license plate number, because as far as I know, Gene never suffered any consequences.

In 1973, there was not a lot of activity going on after work in Victor, except at the Elks Club, Lil’s place, and Zeke’s place. So sometimes I would venture over to Cripple Creek. One night, I went into the Cottage Inn – a place where I came to see my face on the bar room floor more than once to compliment the beautiful lady’s face that was actually imbedded in the Cottage floor. I ran into a rough crowd that night – I believe it included Billy Shoe, Ogre, Charlie Nutall and various other characters of the time. They were all Cripple Creekers and told me that they really didn’t like people from Victor coming into their bar and messing things up. We danced around the room a little bit, but these men were, for the most part, larger than me and I slowly realized that I could take a pretty good beating if I did not do what they wanted me to do. So I laid my head, very long hair and all, on the bar and got doused with a pitcher of beer – baptized so to speak. After that, there appears to have been peace in the valley. Until the constabulary showed up to make sure we all left when the bar closed. My recollection is a bit fuzzy on this, but I think some of the Cripple Creek boys started shoving the deputy around a bit, eventually taking his gun and playing catch with it in Bennett Avenue. I left pretty quickly at that point, so I am not sure how that episode ended.

The "High House". Photo from Randall Stewart.

The "High House". Photo from Randall Stewart.

Around Halloween, 1973, there was a party thrown in Victor – some people in costume. I should mention that at this point, I had very long hair, always tied in a pony-tail that came at least half-way down my back. I cannot remember if I was somehow invited to the party or if I just heard about it and crashed the thing. While there, I saw the best looking woman I had ever seen and been close enough to actually talk to or touch. That was the night I met Shawn. I think I fell in love with her on sight. She had moved to Victor fairly recently at that point with her son Stacy (about 6 or 7 years old then), via Conifer, from California.

At some point late in 1973, D.B. Smith died of a heart attack, leaving a widow. As it happened, she wanted the house D.B. had been living in worked on and improved – so I was made an offer to live in that house – rent free – in exchange for continually making improvements on the house and making it more sellable. I jumped at the chance. Shawn and Stacy moved in with me in that house either in December 1973 or January 1974. Because it was perched high on a hill above most of the rest of the houses in Victor, we quickly named it "the high house". That house was located right above Judy Pratt’s house. She was the head draftsperson at Golden Cycle.

At some point in late 1973 or early 1974, I argued with Jack Hamm, the chief geologist, and Bill Reid, the assistant chief geologist to allow me to obtain a petrographic microscope so that we could view thin sections of rock from the District and look at hand specimens in reflected light. Bill Reid later went on to become President of Silver State Mining, with an operation between Victor and Cripple Creek, and eventually went on to develop Tonkin Springs in Nevada, a bio-leach operation using bacteria to free up gold from refractory ore. After a while, we got a Vickers microscope and I began looking at rock types from the district to try to understand why there was gold there. I remember going to Denver to the USGS to obtain samples of some of the rock from the original work done in the district by Lindgren and Ransome in their 1906 Professional Paper #54, Geology and Gold Deposits of the Cripple Creek District. All that were left were small pieces of the rocks they had looked at – not much help.

The geology of Cripple Creek is unusual – it appears to be some kind of volcanic breccia notched between the Cripple Creek Granite, the Pikes Peak Granite, the Spring Creek Granite, and old metamorphic gneiss (Womack Gneiss). The volcanic rock had a distinctive alkali aspect to it, yielding uncommon rocks such as phonolite, syenite, latite, and lamprophyre along with the far more common basalts. I have long believed that the volcanic activity in the area could have been the result of alkali olivine basalts being subducted underneath California via plate tectonics and working their way to the surface in Colorado on the east side of the Rockies through the interface between the granite and gneiss, differentiating their composition as they rose. But I could never prove it.

After a while, Hamm and Reid sent Tapp and me down the Ajax to the upper workings to conduct mapping of the drifts. I cannot remember if this was 1974 or 1975, probably both years. A magnetic survey had been conducted on every level of the mine to determine the exact orientation of the shaft timbers in relation to the surrounding rock. Markers were placed in the back of each level so that by sighting the markers with a surveying instrument, an exact bearing of the location of the surveying instrument could be determined. This was before GPS technology.

Once we had the original bearing of a heading, we would work in hundred foot sections to survey the orientation of the drift. We would hang a plumb bob from the back at the original site, and another 100 feet down the drift. By sighting and back-sighting, we were able to determine an exact orientation of the drift we were in. We would lay out a 100 foot measuring tape between the two plumb bobs in the center of the drift – sometimes less distance if we were going around a curve. We would then check waist level distances both left and right of center every foot. If the rock was coming toward us – it was a ‘tit’. If the rock was going away from us, it was an ‘ass’. By measuring tits and asses along the drift, we created a profile of the drift – then inspected the rock and mapped it, detailing rock types, faults, and strikes and dips.

Both Tapp and I would finish our designated portion of a drift, return to the surface, go back to the Carlton Mill, redraw our underground maps, and submit them each day. Reid thought we were moving too fast and missing stuff. He ordered us to stay a complete shift underground to do our designated mapping. I don’t know what Tapp did, but I would finish my portion of the drift usually by noon, then turn out the light and go to sleep until the end of shift. Sometimes I would bring comic books down with me to read after I finished mapping.

At some point late in 1973, D.B. Smith died of a heart attack, leaving a widow. As it happened, she wanted the house D.B. had been living in worked on and improved – so I was made an offer to live in that house – rent free – in exchange for continually making improvements on the house and making it more sellable. I jumped at the chance. Shawn and Stacy moved in with me in that house either in December 1973 or January 1974. Because it was perched high on a hill above most of the rest of the houses in Victor, we quickly named it "the high house". That house was located right above Judy Pratt’s house. She was the head draftsperson at Golden Cycle.

At some point in late 1973 or early 1974, I argued with Jack Hamm, the chief geologist, and Bill Reid, the assistant chief geologist to allow me to obtain a petrographic microscope so that we could view thin sections of rock from the District and look at hand specimens in reflected light. Bill Reid later went on to become President of Silver State Mining, with an operation between Victor and Cripple Creek, and eventually went on to develop Tonkin Springs in Nevada, a bio-leach operation using bacteria to free up gold from refractory ore. After a while, we got a Vickers microscope and I began looking at rock types from the district to try to understand why there was gold there. I remember going to Denver to the USGS to obtain samples of some of the rock from the original work done in the district by Lindgren and Ransome in their 1906 Professional Paper #54, Geology and Gold Deposits of the Cripple Creek District. All that were left were small pieces of the rocks they had looked at – not much help.

The geology of Cripple Creek is unusual – it appears to be some kind of volcanic breccia notched between the Cripple Creek Granite, the Pikes Peak Granite, the Spring Creek Granite, and old metamorphic gneiss (Womack Gneiss). The volcanic rock had a distinctive alkali aspect to it, yielding uncommon rocks such as phonolite, syenite, latite, and lamprophyre along with the far more common basalts. I have long believed that the volcanic activity in the area could have been the result of alkali olivine basalts being subducted underneath California via plate tectonics and working their way to the surface in Colorado on the east side of the Rockies through the interface between the granite and gneiss, differentiating their composition as they rose. But I could never prove it.

After a while, Hamm and Reid sent Tapp and me down the Ajax to the upper workings to conduct mapping of the drifts. I cannot remember if this was 1974 or 1975, probably both years. A magnetic survey had been conducted on every level of the mine to determine the exact orientation of the shaft timbers in relation to the surrounding rock. Markers were placed in the back of each level so that by sighting the markers with a surveying instrument, an exact bearing of the location of the surveying instrument could be determined. This was before GPS technology.

Once we had the original bearing of a heading, we would work in hundred foot sections to survey the orientation of the drift. We would hang a plumb bob from the back at the original site, and another 100 feet down the drift. By sighting and back-sighting, we were able to determine an exact orientation of the drift we were in. We would lay out a 100 foot measuring tape between the two plumb bobs in the center of the drift – sometimes less distance if we were going around a curve. We would then check waist level distances both left and right of center every foot. If the rock was coming toward us – it was a ‘tit’. If the rock was going away from us, it was an ‘ass’. By measuring tits and asses along the drift, we created a profile of the drift – then inspected the rock and mapped it, detailing rock types, faults, and strikes and dips.

Both Tapp and I would finish our designated portion of a drift, return to the surface, go back to the Carlton Mill, redraw our underground maps, and submit them each day. Reid thought we were moving too fast and missing stuff. He ordered us to stay a complete shift underground to do our designated mapping. I don’t know what Tapp did, but I would finish my portion of the drift usually by noon, then turn out the light and go to sleep until the end of shift. Sometimes I would bring comic books down with me to read after I finished mapping.

Gas in the Dante & Cresson

At some point, I am pretty sure it was in 1974, Hamm sent me down the Ajax to start taking samples of rock we thought might contain gold, map the location of the samples, and return the labeled rock samples to the assay lab. The first place I was sent to was the Cresson 17 – the Roosevelt Tunnel level. We would go down the Ajax to around the 2000 level, exit the skip, march through a drift to a winze that led down 50 feet or so to the Roosevelt tunnel level. From there, we would walk down the Roosevelt quite a ways to reach the Cresson 17 level workings. We would take samples from the Cresson 17 and I would create a map showing where the samples had come from.

At some point, I am pretty sure it was in 1974, Hamm sent me down the Ajax to start taking samples of rock we thought might contain gold, map the location of the samples, and return the labeled rock samples to the assay lab. The first place I was sent to was the Cresson 17 – the Roosevelt Tunnel level. We would go down the Ajax to around the 2000 level, exit the skip, march through a drift to a winze that led down 50 feet or so to the Roosevelt tunnel level. From there, we would walk down the Roosevelt quite a ways to reach the Cresson 17 level workings. We would take samples from the Cresson 17 and I would create a map showing where the samples had come from.

Roosevelt Tunnel Portal along Shelf Road. If there was a problem with the skip in the shaft of the Ajax Mine Shaft, the only way out was to walk through the Roosevelt or Carlton Drainage Tunnels. Photo from Randall Stewart, 2018.

Roosevelt Tunnel Portal along Shelf Road. If there was a problem with the skip in the shaft of the Ajax Mine Shaft, the only way out was to walk through the Roosevelt or Carlton Drainage Tunnels. Photo from Randall Stewart, 2018.

We eventually worked our way around the Cresson drifts to the old Cresson Vug area. Now that was a big hole in the ground. You could not shine your headlight across that thing as the sphere of light got too big and too diffuse to see the rock on the other side. That stope went several hundred feet above the 17 and several hundred feet below the 17.

I took the idea of rappelling down the stope from the 17 to gather samples to Hamm and Reid, but they quickly told me no–they assured me that I had come up with a crazy and unsafe idea. I don’t remember all the fellows on my crew at the Cresson, but I do remember Tall Ted Johnson showing up one day and going out with us. Another guy I remember is Gary Owen. Ted did OK in the Roosevelt, but when we got to the Cresson workings, which were considerably shorter than the tunnel, Ted kept banging his head against the back. Owen observed that Ted was 5 foot 16 inches in a 5 foot 12 inch drift.

We saw that Cresson Vug stope every day we went down there. I guess that makes us a handful of men who have seen it and are still alive. One day, an ore shoot out there gave way just as we passed and blocked the way out by filling the drift with rock. So we just walked around the vug and were able to have access that way. Toward the end of our Cresson sampling, Hamm and Reid sent us past the Cresson to the old Dante workings. On the far side of the vug, we had to go down about a 10 foot inclined winze, march about 100 or 200 feet along the lower drift, then climb back up an inclined winze to get to the Dante workings. One day the crew was back in there when the naphtha lamp went out. We had gone down on a morning when the atmosphere was heavy (cold air of a low pressure system) and kept the carbon dioxide gas suppressed. But while we were down there, a front moved in and left lighter air (atmospheric high system) over the Cresson – allowing the CO2 gas to start to rise. We determined that the gas had come up to our knees. So I sent the men back through the winzes one at a time, telling them not to breathe while down in the lower level, because I was not hauling their butts out – they were all too big. I was the last man to leave the Dante and head back toward the Cresson. On the Cresson side, the gas was about waist level according to the lamp when I got through. We all walked briskly toward the Roosevelt – I cautioned the men not to false step, because if they went down, it would be hard on the rest of us to save their butt. Of course, I insisted that every man keep packing the rocks we had collected from the Dante earlier. When we reached the Roosevelt Tunnel, the gas was just below my chin – and I was the shortest guy down there. The Roosevelt was a wind tunnel, connected to both the top of the Ajax and other mines and the surface at the tunnel portal. Once we were in the tunnel, we had good air and we made our way back to the Ajax shaft and got out before we got gassed.

On another day, there was an accident in the shaft. The shaft was all timbered, and the skips attached to the hoist were made of steel. The skips had devices called dogs attached to them that helped guide the skips up or down the shaft by running on the guide posts in the shaft. The skips were counter-balanced, that is, while one went up, the other went down. One of the skips started bouncing while in motion, and the dogs engaged, stopping the skip in the shaft, The wire rope attached to the hoist piled up on top of that skip, and eventually the skip coming the other direction ran into the pile of rope, stopping it in the shaft as well, shutting the shaft down. The men on 31 had to go out the Carlton Tunnel. Bill Reid and his crew were trapped on 14 and had to wait out the repair of the accident in the shaft and their eventual rescue. My crew was once again in the Dante, and thus, the Roosevelt Tunnel level. Somehow (I forget exactly how we found out), we started walking down the Roosevelt. On the way out, we met Jack Hamm, who had come in the portal to find us and check on us. He was very glad that we were all safe – and that we had hauled our samples out.

In 1974, the Teller County Treasurer decided to clear the books of all unpaid property taxes. As a result, land all over the district went up for auction – highest bidder being the winner. I had the advantage of access to many maps, and was able to locate a wonderful property in Goldfield listed by defunct city block units. By conducting my own survey, I was able to translate the city block units being sold at auction into a fairly accurate location of where those units actually were – and what was located on them. I won the bid for the property I had focused on and immediately hired a Registered Land Surveyor to relocate the boundaries of the city block units of the Goldfield property. I still owned this property located on the flat just above the Goldfield Arena, until early in 2017, when I sold it to Newmont Mining.

I took the idea of rappelling down the stope from the 17 to gather samples to Hamm and Reid, but they quickly told me no–they assured me that I had come up with a crazy and unsafe idea. I don’t remember all the fellows on my crew at the Cresson, but I do remember Tall Ted Johnson showing up one day and going out with us. Another guy I remember is Gary Owen. Ted did OK in the Roosevelt, but when we got to the Cresson workings, which were considerably shorter than the tunnel, Ted kept banging his head against the back. Owen observed that Ted was 5 foot 16 inches in a 5 foot 12 inch drift.

We saw that Cresson Vug stope every day we went down there. I guess that makes us a handful of men who have seen it and are still alive. One day, an ore shoot out there gave way just as we passed and blocked the way out by filling the drift with rock. So we just walked around the vug and were able to have access that way. Toward the end of our Cresson sampling, Hamm and Reid sent us past the Cresson to the old Dante workings. On the far side of the vug, we had to go down about a 10 foot inclined winze, march about 100 or 200 feet along the lower drift, then climb back up an inclined winze to get to the Dante workings. One day the crew was back in there when the naphtha lamp went out. We had gone down on a morning when the atmosphere was heavy (cold air of a low pressure system) and kept the carbon dioxide gas suppressed. But while we were down there, a front moved in and left lighter air (atmospheric high system) over the Cresson – allowing the CO2 gas to start to rise. We determined that the gas had come up to our knees. So I sent the men back through the winzes one at a time, telling them not to breathe while down in the lower level, because I was not hauling their butts out – they were all too big. I was the last man to leave the Dante and head back toward the Cresson. On the Cresson side, the gas was about waist level according to the lamp when I got through. We all walked briskly toward the Roosevelt – I cautioned the men not to false step, because if they went down, it would be hard on the rest of us to save their butt. Of course, I insisted that every man keep packing the rocks we had collected from the Dante earlier. When we reached the Roosevelt Tunnel, the gas was just below my chin – and I was the shortest guy down there. The Roosevelt was a wind tunnel, connected to both the top of the Ajax and other mines and the surface at the tunnel portal. Once we were in the tunnel, we had good air and we made our way back to the Ajax shaft and got out before we got gassed.

On another day, there was an accident in the shaft. The shaft was all timbered, and the skips attached to the hoist were made of steel. The skips had devices called dogs attached to them that helped guide the skips up or down the shaft by running on the guide posts in the shaft. The skips were counter-balanced, that is, while one went up, the other went down. One of the skips started bouncing while in motion, and the dogs engaged, stopping the skip in the shaft, The wire rope attached to the hoist piled up on top of that skip, and eventually the skip coming the other direction ran into the pile of rope, stopping it in the shaft as well, shutting the shaft down. The men on 31 had to go out the Carlton Tunnel. Bill Reid and his crew were trapped on 14 and had to wait out the repair of the accident in the shaft and their eventual rescue. My crew was once again in the Dante, and thus, the Roosevelt Tunnel level. Somehow (I forget exactly how we found out), we started walking down the Roosevelt. On the way out, we met Jack Hamm, who had come in the portal to find us and check on us. He was very glad that we were all safe – and that we had hauled our samples out.

In 1974, the Teller County Treasurer decided to clear the books of all unpaid property taxes. As a result, land all over the district went up for auction – highest bidder being the winner. I had the advantage of access to many maps, and was able to locate a wonderful property in Goldfield listed by defunct city block units. By conducting my own survey, I was able to translate the city block units being sold at auction into a fairly accurate location of where those units actually were – and what was located on them. I won the bid for the property I had focused on and immediately hired a Registered Land Surveyor to relocate the boundaries of the city block units of the Goldfield property. I still owned this property located on the flat just above the Goldfield Arena, until early in 2017, when I sold it to Newmont Mining.

Trip to World’s Fair in Spokane

Shawn and Stacy and I decided we would go to the World’s Fair being held in Spokane, Washington during August of 1974. I had a little red Fiat that we drove. We went up through Wyoming and Montana and Yellowstone National Park to Glacier National Park on our way to take a quick excursion into Canada. That Fiat kept overheating and the only way we had to keep the engine cool enough to keep going was to turn on the heater in the car to dissipate the engine heat – in August. Stacy, in the back seat, must have begun to hate me and that car on that trip. On the way through customs, we must have fit some kind of profile because we got pulled out of line and had the car searched. The Mounties found the stash of pot I had placed in the rim of the car trunk. But they did not find the much bigger stash that was hidden in the cereal box in the car. The Mounties told me that all they found was a small amount of marijuana, hardly worth bothering with – but they knew I was hiding a lot more. They told me that if I confessed and showed them the stash, they would go easy with me, but that if I lied and told them I had no stash and they later found it, they would throw the book at me. I lied right to their faces and told them they had found all the pot I had. They never found the stash in the cereal. Shawn and Stacy returned with the Fiat to the U.S. and I was taken by the Mounties to jail in Creston, British Columbia. I sat in the jail for most of two days while phone calls I made to allies in the U.S. finally paid off. I appeared in front of a judge who told me I owed $200 US as a fine, which I now had, and which I paid to the court. I was deported from Canada as an Undesirable Alien back to the U.S. Shawn and Stacy met me at the border and we proceeded on to Spokane. We arrived at the World’s Fair, but had no money left to go in. We barely had the cash to return to Victor and eat along the way, so we headed home.

Easter Party

For Easter, 1975, Shawn and I planned a party for all of our friends. That happened on March 30th that year. We sent all the children down the hill to Sandra’s house with two gallons of ice cream and the promise for them to watch The Wizard of Oz on TV. Most of the adults stayed at the "high house" and partied. Brian and Rosemary Hayes were there, along with many others whom I cannot recall. We consumed a lot of adult beverages and marijuana and made a lot of noise. Neighbors reported the party to the police, who showed up at the "high house". We promised to be better and they left, only to return later with the same complaint from our loud music and outrageous behavior. This time we invited them in – and they accepted, for a while. We had no further issues with noise complaints after that. Kevin Ranftle decided he wanted to paint his bald (shaved) head like an Easter Egg, and Shawn helped him do it. Kevin left the "high house" party and went straight down to Zeke’s. Strangers at the bar wanted to buy the ‘Egg’ a beer, so Kevin accepted. He stayed drunk for a week with his painted egg head and the kindness of others.

Shawn and Stacy and I decided we would go to the World’s Fair being held in Spokane, Washington during August of 1974. I had a little red Fiat that we drove. We went up through Wyoming and Montana and Yellowstone National Park to Glacier National Park on our way to take a quick excursion into Canada. That Fiat kept overheating and the only way we had to keep the engine cool enough to keep going was to turn on the heater in the car to dissipate the engine heat – in August. Stacy, in the back seat, must have begun to hate me and that car on that trip. On the way through customs, we must have fit some kind of profile because we got pulled out of line and had the car searched. The Mounties found the stash of pot I had placed in the rim of the car trunk. But they did not find the much bigger stash that was hidden in the cereal box in the car. The Mounties told me that all they found was a small amount of marijuana, hardly worth bothering with – but they knew I was hiding a lot more. They told me that if I confessed and showed them the stash, they would go easy with me, but that if I lied and told them I had no stash and they later found it, they would throw the book at me. I lied right to their faces and told them they had found all the pot I had. They never found the stash in the cereal. Shawn and Stacy returned with the Fiat to the U.S. and I was taken by the Mounties to jail in Creston, British Columbia. I sat in the jail for most of two days while phone calls I made to allies in the U.S. finally paid off. I appeared in front of a judge who told me I owed $200 US as a fine, which I now had, and which I paid to the court. I was deported from Canada as an Undesirable Alien back to the U.S. Shawn and Stacy met me at the border and we proceeded on to Spokane. We arrived at the World’s Fair, but had no money left to go in. We barely had the cash to return to Victor and eat along the way, so we headed home.

Easter Party

For Easter, 1975, Shawn and I planned a party for all of our friends. That happened on March 30th that year. We sent all the children down the hill to Sandra’s house with two gallons of ice cream and the promise for them to watch The Wizard of Oz on TV. Most of the adults stayed at the "high house" and partied. Brian and Rosemary Hayes were there, along with many others whom I cannot recall. We consumed a lot of adult beverages and marijuana and made a lot of noise. Neighbors reported the party to the police, who showed up at the "high house". We promised to be better and they left, only to return later with the same complaint from our loud music and outrageous behavior. This time we invited them in – and they accepted, for a while. We had no further issues with noise complaints after that. Kevin Ranftle decided he wanted to paint his bald (shaved) head like an Easter Egg, and Shawn helped him do it. Kevin left the "high house" party and went straight down to Zeke’s. Strangers at the bar wanted to buy the ‘Egg’ a beer, so Kevin accepted. He stayed drunk for a week with his painted egg head and the kindness of others.

Laid Off, Move to Goldfield Property—Randalltown

I got laid off from Golden Cycle Gold in May 1975 when times got too tough for the Ajax operation, just before Golden Cycle merged with Texas Gulf. Because I had the deal with D.B. Smith’s widow to stay in the "high house" and improve it (which I tried to do), when I got dumped by Golden Cycle, it was not long after that when I was asked to vacate the house by Golden Cycle bosses. Shortly after that, Shawn and I split up, breaking my heart.

I was forced to move out of the "high house" and out to Goldfield to the property I had purchased at auction. Over time, it came to be known as Randalltown. It was a real struggle to survive in the district during the second half of 1975. I moved into the cabin, which was habitable with a wood/coal burning stove. I used kerosene lamps at night, and cooked meals on the stove, which also provided needed heat in the winter. I had to haul water in five gallon containers. Eventually I found and added an old railroad heater to the cabin, and between the stove and the heater, I was able to stay plenty warm in the cold months of winter, as long as I could provide wood and coal to burn in them.

I got laid off from Golden Cycle Gold in May 1975 when times got too tough for the Ajax operation, just before Golden Cycle merged with Texas Gulf. Because I had the deal with D.B. Smith’s widow to stay in the "high house" and improve it (which I tried to do), when I got dumped by Golden Cycle, it was not long after that when I was asked to vacate the house by Golden Cycle bosses. Shortly after that, Shawn and I split up, breaking my heart.

I was forced to move out of the "high house" and out to Goldfield to the property I had purchased at auction. Over time, it came to be known as Randalltown. It was a real struggle to survive in the district during the second half of 1975. I moved into the cabin, which was habitable with a wood/coal burning stove. I used kerosene lamps at night, and cooked meals on the stove, which also provided needed heat in the winter. I had to haul water in five gallon containers. Eventually I found and added an old railroad heater to the cabin, and between the stove and the heater, I was able to stay plenty warm in the cold months of winter, as long as I could provide wood and coal to burn in them.

Working the El Paso Mine Tours

Sometime in 1975 or early 1976, while tourists were still coming up to Cripple, I went to work for Dale Weaver over at the El Paso Mine, guiding tours. I can’t remember what level we ran those tours on, but I did a lot of them. A big highlight for old Dale was to get the tourists into his gift shop after the tour. One thing in particular I remember him trying to sell was round pieces of leather with the word ‘tuit’ carved into them. He thought it was pretty funny that people could finally get around to it – whatever it was. I think I did that job for several months. I know I worked for tip money, but I can’t remember whether or not I actually got paid a wage by Dale or not.

Sometime in 1975 or early 1976, while tourists were still coming up to Cripple, I went to work for Dale Weaver over at the El Paso Mine, guiding tours. I can’t remember what level we ran those tours on, but I did a lot of them. A big highlight for old Dale was to get the tourists into his gift shop after the tour. One thing in particular I remember him trying to sell was round pieces of leather with the word ‘tuit’ carved into them. He thought it was pretty funny that people could finally get around to it – whatever it was. I think I did that job for several months. I know I worked for tip money, but I can’t remember whether or not I actually got paid a wage by Dale or not.

Gold Camp Friends

Mike and Suzy Phillips were brother and sister and came up to Cripple probably around 1975 or so. They were part of the crowd I hung around with starting after I got laid off by Golden Cycle. Mike may have come up first followed a while later by his sister. They were from somewhere back east – but fell in love with Cripple Creek and Victor and stayed up there for many years. I can’t remember if one or both of them were at the Easter egg party or not. Suzy later hooked up with Kevin Ranftle. Mike and I became pretty good friends over time. I don’t think Mike ever made it underground.

Mike Bledsoe showed up in Cripple sometime in 1975 or 1976. He lost the vision in one eye and some of the vision in the other eye when a mine exploded in front of him in Vietnam. He told me once that flying parts of the men in front of him that actually triggered the mine is what caused his loss of vision. Bledsoe specialized in his ‘little dears’ and turning them loose on an unsuspecting America.

One summer, I think it was 1975 or 1976, Bledsoe and I took a contract to paint the roof of the Cripple Creek Museum. Mike would get out on the edge of the roof with a can of paint and a broom-like paint brush and slop on the new paint. I stayed in the roof access area standing on a ladder holding on to the rope we had tied around Mike’s waist. Not sure I would have been able to do much to prevent a fall if he actually lost his balance or footing and took a plunge – but I would have tried. There was a steel fence with pointy tops in front of the museum positioned perfectly to impale anything coming off that roof. After a few hours of work each day, we would go see the curator and demand our day’s pay (which he reluctantly gave us, because no one else would take the paint job) and proceed down to the Imperial or Cottage and drink that pay up.

I met Bruce and Charlie Luck in 1974 or 1975. They were from New York State and took over or re-opened the Cripple Creek Inn on Bennett Avenue. We all had a great deal of fun for a few years at the Cripple Creek Inn. Most weekends, there was a band and dancing.

The girls – Sue, Judy and Nan, moved into the "low house" at the bottom of Victor in 1975 or 1976. They certainly livened up the place and their house was the scene of many a party and lots of fun. Not sure how long the girls stayed up there, but I know I saw Sue in the summer of 1979. There was always a large group of men hanging around the girls while they were up there.

Mike and Suzy Phillips were brother and sister and came up to Cripple probably around 1975 or so. They were part of the crowd I hung around with starting after I got laid off by Golden Cycle. Mike may have come up first followed a while later by his sister. They were from somewhere back east – but fell in love with Cripple Creek and Victor and stayed up there for many years. I can’t remember if one or both of them were at the Easter egg party or not. Suzy later hooked up with Kevin Ranftle. Mike and I became pretty good friends over time. I don’t think Mike ever made it underground.

Mike Bledsoe showed up in Cripple sometime in 1975 or 1976. He lost the vision in one eye and some of the vision in the other eye when a mine exploded in front of him in Vietnam. He told me once that flying parts of the men in front of him that actually triggered the mine is what caused his loss of vision. Bledsoe specialized in his ‘little dears’ and turning them loose on an unsuspecting America.

One summer, I think it was 1975 or 1976, Bledsoe and I took a contract to paint the roof of the Cripple Creek Museum. Mike would get out on the edge of the roof with a can of paint and a broom-like paint brush and slop on the new paint. I stayed in the roof access area standing on a ladder holding on to the rope we had tied around Mike’s waist. Not sure I would have been able to do much to prevent a fall if he actually lost his balance or footing and took a plunge – but I would have tried. There was a steel fence with pointy tops in front of the museum positioned perfectly to impale anything coming off that roof. After a few hours of work each day, we would go see the curator and demand our day’s pay (which he reluctantly gave us, because no one else would take the paint job) and proceed down to the Imperial or Cottage and drink that pay up.

I met Bruce and Charlie Luck in 1974 or 1975. They were from New York State and took over or re-opened the Cripple Creek Inn on Bennett Avenue. We all had a great deal of fun for a few years at the Cripple Creek Inn. Most weekends, there was a band and dancing.

The girls – Sue, Judy and Nan, moved into the "low house" at the bottom of Victor in 1975 or 1976. They certainly livened up the place and their house was the scene of many a party and lots of fun. Not sure how long the girls stayed up there, but I know I saw Sue in the summer of 1979. There was always a large group of men hanging around the girls while they were up there.

Surveying, Mapping & Driving Drift in the Gold Bond

In May, 1976, I was sitting in a bar in Cripple Creek, when I met Al Goodwin, Manager at the Gold Bond Mine, just south of town. I explained to him that I was a geologist, used to work at the Ajax, and was experienced at underground surveying and mapping. Al hired me to survey the Gold Bond – all 4 levels. Jim Brownlee worked with me over the time it took to survey and map the mine (weeks I think). The owners of the operation were called Reeves Minerals.

We didn’t have a fancy theodolite like we used at the Ajax to set the orientation of the drift on every level. We sighted in the vertical wood sections of the shaft timber and set our markers in the back from there. The 100 foot section and ‘tits and ass’ method was used at the Gold Bond, just as it was used at the Ajax. While drawing up the results, I got one of the levels reversed. The resulting drawing showed drift workings that did not exist. It showed a drift going off in a direction 180 degrees different than all the other drifts in the mine. Al freaked out over that one, thinking there might be an entire unexplored vein system. After a while, I figured out my error, corrected the drawings to show how all four levels of the mine were coincident on the same vein system, and submitted the final results to Al. He was not pleased that I had got him excited over nothing. But he did not fire me.

Instead, he offered me a job working underground as a miner. I worked running bald-headed raises through August of 1976. I also worked at the Gold Bond from June to August in 1979. I drove about 400 yards of drift on level 4 and ran three 75 foot high bald-headed raises. Old Jim Young showed me how to run a jackleg and a stoper. I was working with Greg Pratt in 1976 running bald headed raises, but my mining partner in 1979 was Brian Marshall. Over time, I met all three Pratt Brothers (no relation to Judy) – John, Greg and Larry. I’m pretty sure that John was hoisting in 1976, but my recollection of 1979 was that Larry was the hoist man.

In May, 1976, I was sitting in a bar in Cripple Creek, when I met Al Goodwin, Manager at the Gold Bond Mine, just south of town. I explained to him that I was a geologist, used to work at the Ajax, and was experienced at underground surveying and mapping. Al hired me to survey the Gold Bond – all 4 levels. Jim Brownlee worked with me over the time it took to survey and map the mine (weeks I think). The owners of the operation were called Reeves Minerals.

We didn’t have a fancy theodolite like we used at the Ajax to set the orientation of the drift on every level. We sighted in the vertical wood sections of the shaft timber and set our markers in the back from there. The 100 foot section and ‘tits and ass’ method was used at the Gold Bond, just as it was used at the Ajax. While drawing up the results, I got one of the levels reversed. The resulting drawing showed drift workings that did not exist. It showed a drift going off in a direction 180 degrees different than all the other drifts in the mine. Al freaked out over that one, thinking there might be an entire unexplored vein system. After a while, I figured out my error, corrected the drawings to show how all four levels of the mine were coincident on the same vein system, and submitted the final results to Al. He was not pleased that I had got him excited over nothing. But he did not fire me.

Instead, he offered me a job working underground as a miner. I worked running bald-headed raises through August of 1976. I also worked at the Gold Bond from June to August in 1979. I drove about 400 yards of drift on level 4 and ran three 75 foot high bald-headed raises. Old Jim Young showed me how to run a jackleg and a stoper. I was working with Greg Pratt in 1976 running bald headed raises, but my mining partner in 1979 was Brian Marshall. Over time, I met all three Pratt Brothers (no relation to Judy) – John, Greg and Larry. I’m pretty sure that John was hoisting in 1976, but my recollection of 1979 was that Larry was the hoist man.

When we were driving drift, in addition to drilling the holes, loading them with dynamite and ammonium nitrate and shooting them, we had to extend our water line and plastic air tubing, bringing fresh air ventilation to the face. We also had to bring our rubber air hose with us to provide compressed air to run the jackleg with. As we advanced the face, we had to extend the ore car track. When we finished placing and securing a rail section, we would lay the next section on its side, inside of the vertical, secured rail. The mucking machine would run on these flat lying rails as we extended it out and eventually were able to stand them up and spike them into place vertically. While I was learning how to work it, I knocked that mucker off the temporary tracks too many times to count. Eventually, I got pretty good with that machine, and could muck out a round and keep the mucker on the tracks.

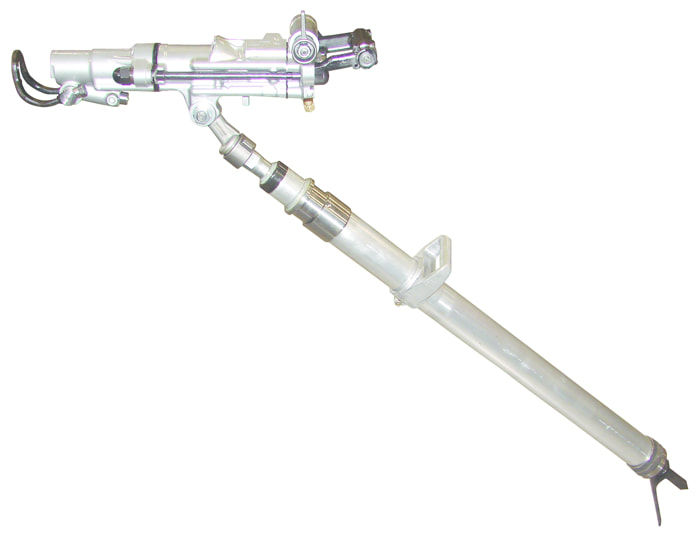

BBD 46WS/WR Stoper for production drilling, raise driving and bolting in soft to medium hard rock. Photo from Randall Stewart, 2018.

BBD 46WS/WR Stoper for production drilling, raise driving and bolting in soft to medium hard rock. Photo from Randall Stewart, 2018.

When we were working in a raise, we worked off the pile of rocks from the previous shot until the raise got too high to work off that rock pile. After that, we had to notch a platform into the surrounding rock of the raise and build ladders to climb up on. Wooden shims were pounded into the notches between the rock and platform supports to keep the structure stable and strong. We would place three inch thick wood planks on top of the structure to stand on and set the stoper so we could drill.

You used a short piece of steel, followed by longer and longer pieces of steel until you had drilled deep enough for a round. Nothing was over our heads but the rock face we had just blasted – bald-headed. Of course, water and mud continually got in our eyes as we drilled upward. Only wimps wore goggles. Besides, goggles got totally covered with mud very quickly, and no one had figured out how to put a windshield wiper on them.

We had to take that platform out each time we shot a round, or we would have broken and destroyed the wooden planks and support timber many times over – it was labor intensive, because we had to rebuild that structure after each round to get back up there to the back we were drilling for the next round.

It didn’t matter if we were driving drift or raising – after we drilled out a round, we had to load those holes with explosive to shoot them. First thing we did was push a real big steel nail trough a stick of dynamite at an angle. Then, you’d stick a blasting cap connected to burn rope into that hole. You’d put that stick of dynamite into a drill hole blasting cap first, with the burn rope trailing behind. Next, you’d push that dynamite into the hole with a stick all the way to the end. Once the dynamite was in place, you’d start slamming the back of the dynamite with the push stick – as hard as you could slam it – to break it up and spread it out to fill the hole. Then you’d put in another stick of dynamite and do the same thing, this time without the blasting cap. Then you’d use the air hose to shoot in the ammonium nitrate. The first time I had to slam that stick of dynamite, I just tapped it. Old Jim Young told me to hit that stick as hard as I could – it took me a while to get the hang of it – but I did figure it out. Finally, all of the burn rope was sticking out of the face when each hole was filled. You’d hook each burn rope to the primer cord with some device I forget, and eventually have the face ready to shoot. In a drift, the first holes to blow were in the middle of the face, called the burn, followed by the sides (ribs) and back. The last holes to blow were the ‘lifters’ – the bottom holes designed to ‘lift’ and move the muck pile back and away from the face – making it easier to come in and muck up.

You used a short piece of steel, followed by longer and longer pieces of steel until you had drilled deep enough for a round. Nothing was over our heads but the rock face we had just blasted – bald-headed. Of course, water and mud continually got in our eyes as we drilled upward. Only wimps wore goggles. Besides, goggles got totally covered with mud very quickly, and no one had figured out how to put a windshield wiper on them.

We had to take that platform out each time we shot a round, or we would have broken and destroyed the wooden planks and support timber many times over – it was labor intensive, because we had to rebuild that structure after each round to get back up there to the back we were drilling for the next round.

It didn’t matter if we were driving drift or raising – after we drilled out a round, we had to load those holes with explosive to shoot them. First thing we did was push a real big steel nail trough a stick of dynamite at an angle. Then, you’d stick a blasting cap connected to burn rope into that hole. You’d put that stick of dynamite into a drill hole blasting cap first, with the burn rope trailing behind. Next, you’d push that dynamite into the hole with a stick all the way to the end. Once the dynamite was in place, you’d start slamming the back of the dynamite with the push stick – as hard as you could slam it – to break it up and spread it out to fill the hole. Then you’d put in another stick of dynamite and do the same thing, this time without the blasting cap. Then you’d use the air hose to shoot in the ammonium nitrate. The first time I had to slam that stick of dynamite, I just tapped it. Old Jim Young told me to hit that stick as hard as I could – it took me a while to get the hang of it – but I did figure it out. Finally, all of the burn rope was sticking out of the face when each hole was filled. You’d hook each burn rope to the primer cord with some device I forget, and eventually have the face ready to shoot. In a drift, the first holes to blow were in the middle of the face, called the burn, followed by the sides (ribs) and back. The last holes to blow were the ‘lifters’ – the bottom holes designed to ‘lift’ and move the muck pile back and away from the face – making it easier to come in and muck up.

After leaving the District in 1976 I took a series of jobs—working on a Peat Moss deposit near Aspen, watching over oils wells near Eagle Pass, Texas, and selling seismic data to petroleum companies from Houston. Eventually I started a graduate program in Geology in at the University of Houston 1978.

In the summer of 1978, I came back to the District and played some softball with the local Cripple team, which included Kevin, Charlie and Bruce Luck, and a whole cast of other characters over the years. We played in a Woodland Park church league, calling ourselves the Small Town Drunks. We won the championship that summer and as I recall, the church teams were not too happy with us – especially since most of us were drinking beer throughout each game.

I remember one pickup practice game we were playing over in Victor at the ball field down below the Elks Club. I misjudged a high fly ball and caught it right between the eyes, knocking me out for a while. The boys made me quit for the day, but Megan Murphy rescued me and took me down to her house to recover—another beautiful, tall redhead. Anyway, while down there, Megan told me about an all-women’s softball team she was thinking of forming. She told me she wanted their team name to be the Cunning Runts. I had a pretty good chuckle over that one.

In the summer of 1978, I came back to the District and played some softball with the local Cripple team, which included Kevin, Charlie and Bruce Luck, and a whole cast of other characters over the years. We played in a Woodland Park church league, calling ourselves the Small Town Drunks. We won the championship that summer and as I recall, the church teams were not too happy with us – especially since most of us were drinking beer throughout each game.

I remember one pickup practice game we were playing over in Victor at the ball field down below the Elks Club. I misjudged a high fly ball and caught it right between the eyes, knocking me out for a while. The boys made me quit for the day, but Megan Murphy rescued me and took me down to her house to recover—another beautiful, tall redhead. Anyway, while down there, Megan told me about an all-women’s softball team she was thinking of forming. She told me she wanted their team name to be the Cunning Runts. I had a pretty good chuckle over that one.

Bad Steel in the Gold Bond Mine

I worked all summer at the Gold Bond in 1979. Brian Marshall and I drove drift from June through August of 1979. Sometime that summer Brian and I were driving drift on the Gold Bond 400 level. I remember picking up that jackleg and trotting down the drift with it to the heading. That thing weighed about 85 pounds – while I weighed 135 pounds at the time. Underground mining is a tough job, but Brian and I got our round every day.

One day, we were having a bad steel day – rough rock to drill through, and we broke a 6 foot piece of steel in the face early in the morning. Al Goodwin got perturbed at us telling us that we were breaking too much steel and costing him too much money – he wanted us to be more careful with the steel. But he sent a new piece of steel on down the skip for us to keep drilling with.

Some guys would push that jackleg with their body to make it move faster. I was not big enough to get any advantage doing that, so I learned how to make that jackleg drill the holes by itself – with me controlling it by holding the air hose in one hand and the water hose in the other – and squeezing one or the other to make the drill turn faster or slower, with more or less pressure, and using more or less water at the end of that hole. If you got that steel compromised at too great an angle due to too much pressure, you could break steel that way – so I learned not to do that. The only time I would use my body to push the drill into the hole faster was on the lifters – the bottom of the drift holes – because I could get an advantage by leaning into it.

We put that new piece of steel in the drill and started work on the lifters – I was drilling. There was about a 100 or 100+ psi (pounds per square inch) air pressure running into the drill from the compressor up on the surface. I was leaning on the jackleg pushing those lifters, and darned if I didn’t break that brand new piece of steel. Snapped it right in two. Problem was, the drill shot forward before I could react, dragging me forward toward the face with it – and right toward the steel sticking out of the lifter hole I was drilling. I could see that piece of steel coming right at my head – or rather – my head coming right at the steel in the rock. All I could do was move my head to the side as far as I could and pray. My hardhat slammed into the face and I came to a stop, laying on top of the jackleg, which was still running. I’m pretty sure Brian figured I had just impaled myself on that broken steel, and that he had a dead partner to have to deal with. But after a short while, I reached my arm up and shut off the air and water – he knew I was OK then. We sat for a bit wondering how I had not gotten impaled on that steel piece, and then we took the two broken pieces back to the shaft, put them in the skip, and asked for a third piece of steel that day. All we could think of was how mad Al was going to be about breaking his steel.

We finally finished and shot that round that day and returned to the surface. After telling the top hands what had happened, Larry pulled us aside and showed us that second piece of broken steel. He told us that Al had found that steel out in the front yard of his house in Cripple – and it looked perfectly good to him, so he had sent it on down. Problem was, Larry showed us that the steel had rusted just about all the way through—right along a hair line fracture that was so thin you couldn’t see it when the steel was in one piece, no way we could have seen it underground. No telling how long that steel had laid out in Al’s yard exposed to the elements. Now it was my turn to get angry about broken steel. I could have been killed by using bad steel– someone had seen it in the past and thrown the steel away in the yard, but Al was a bit on the cheap side so it made perfect sense to him that he use it. When we confronted Al about the steel, he did feel mighty bad about it. After that, we didn’t hear any more about too much broken steel – he knew he’d get reminded of the steel from the yard that almost got embedded in my face.

The summer of 1979 was my last days of mining underground up in Cripple. Sure was fun – glad I did it – but it was hard work and hard on the body. I guess I am glad I didn’t continue doing that for a living and be faced with still trying to do it at my age.

I was offered a position to be a Teaching Assistant in the UH Geology Department for the Fall 1979 semester – now I would be paid to go to school. I got married in 1980 in Houston, and eventually graduated from the University of Houston with a Master’s degree in Geology in 1984.

I worked for a short time (1981 – 1982) for Phelps Dodge in their Small Mines Division in Morenci, AZ. I got hired in when copper prices were around $1.30/pound – then a strong recession occurred and the price of copper dropped below $1.00 pound in 1982 – and I got laid off. That ended my connection with underground mining. So I returned to Houston.

Years later, in 1989, when I was back in Houston, I managed to land a job with FMC Corporation. The job was marketing and selling liquid sodium cyanide to the gold and silver mines in Nevada. I worked that job for 12 ½ years through May, 2002. That definitely ended my career in the mining industry.

I worked all summer at the Gold Bond in 1979. Brian Marshall and I drove drift from June through August of 1979. Sometime that summer Brian and I were driving drift on the Gold Bond 400 level. I remember picking up that jackleg and trotting down the drift with it to the heading. That thing weighed about 85 pounds – while I weighed 135 pounds at the time. Underground mining is a tough job, but Brian and I got our round every day.

One day, we were having a bad steel day – rough rock to drill through, and we broke a 6 foot piece of steel in the face early in the morning. Al Goodwin got perturbed at us telling us that we were breaking too much steel and costing him too much money – he wanted us to be more careful with the steel. But he sent a new piece of steel on down the skip for us to keep drilling with.

Some guys would push that jackleg with their body to make it move faster. I was not big enough to get any advantage doing that, so I learned how to make that jackleg drill the holes by itself – with me controlling it by holding the air hose in one hand and the water hose in the other – and squeezing one or the other to make the drill turn faster or slower, with more or less pressure, and using more or less water at the end of that hole. If you got that steel compromised at too great an angle due to too much pressure, you could break steel that way – so I learned not to do that. The only time I would use my body to push the drill into the hole faster was on the lifters – the bottom of the drift holes – because I could get an advantage by leaning into it.

We put that new piece of steel in the drill and started work on the lifters – I was drilling. There was about a 100 or 100+ psi (pounds per square inch) air pressure running into the drill from the compressor up on the surface. I was leaning on the jackleg pushing those lifters, and darned if I didn’t break that brand new piece of steel. Snapped it right in two. Problem was, the drill shot forward before I could react, dragging me forward toward the face with it – and right toward the steel sticking out of the lifter hole I was drilling. I could see that piece of steel coming right at my head – or rather – my head coming right at the steel in the rock. All I could do was move my head to the side as far as I could and pray. My hardhat slammed into the face and I came to a stop, laying on top of the jackleg, which was still running. I’m pretty sure Brian figured I had just impaled myself on that broken steel, and that he had a dead partner to have to deal with. But after a short while, I reached my arm up and shut off the air and water – he knew I was OK then. We sat for a bit wondering how I had not gotten impaled on that steel piece, and then we took the two broken pieces back to the shaft, put them in the skip, and asked for a third piece of steel that day. All we could think of was how mad Al was going to be about breaking his steel.