Ajax Skip – Photo by Charles Clark ©, Click to Enlarge.

Ajax Skip – Photo by Charles Clark ©, Click to Enlarge.

UNDERGROUND MINING EXPERIENCES AT THE CRESSON & AJAX

By Myron House

I graduated from Cripple Creek High School on May 15, 1951. I went to work for the Golden Cycle Mining Company and started at the Cresson Mine running the top car. When the skip came to the surface it would dump the rock into the top car and I would take the ore to the ore house or waste to the dump.

I couldn’t go underground until I was 18, and on May 24th I turned 18. I asked the mine superintendent, Charlie Carlton, if I could go underground. He said he would think about it. A few days later he said he had talked to my parents and it was okay. This was to be my first experience as a miner underground.

I had to buy a hard hat before I could go underground. I also needed work clothes before my first day. With my parents help, I bought coveralls with buckles over the shoulders and lots of pockets, work boots with steel toes and heavy shirts. I needed a metal lunch bucket; sacks would not work because of the moisture in the mine.

I had some apprehension the first time getting into the skip to go underground. Three men got in the skip, another three in the next row and two in the last row. That left one space open. If they had put someone in that space, we wouldn’t have been able to get out. We had our hard hats on, a wide belt around our waist that held the battery for the light on our helmets and the hoist lowered the skip underground. Later on when I worked at the Ajax mine, we wore yellow slickers because the water would splash on us going down the shaft. Down to the 30th level—3,111 feet straight down. The Ajax mine tunnels were under Victor, Colorado. I told my wife Rita that I was working under the Flanagan house, but 3,000 feet below.

By Myron House

I graduated from Cripple Creek High School on May 15, 1951. I went to work for the Golden Cycle Mining Company and started at the Cresson Mine running the top car. When the skip came to the surface it would dump the rock into the top car and I would take the ore to the ore house or waste to the dump.

I couldn’t go underground until I was 18, and on May 24th I turned 18. I asked the mine superintendent, Charlie Carlton, if I could go underground. He said he would think about it. A few days later he said he had talked to my parents and it was okay. This was to be my first experience as a miner underground.

I had to buy a hard hat before I could go underground. I also needed work clothes before my first day. With my parents help, I bought coveralls with buckles over the shoulders and lots of pockets, work boots with steel toes and heavy shirts. I needed a metal lunch bucket; sacks would not work because of the moisture in the mine.

I had some apprehension the first time getting into the skip to go underground. Three men got in the skip, another three in the next row and two in the last row. That left one space open. If they had put someone in that space, we wouldn’t have been able to get out. We had our hard hats on, a wide belt around our waist that held the battery for the light on our helmets and the hoist lowered the skip underground. Later on when I worked at the Ajax mine, we wore yellow slickers because the water would splash on us going down the shaft. Down to the 30th level—3,111 feet straight down. The Ajax mine tunnels were under Victor, Colorado. I told my wife Rita that I was working under the Flanagan house, but 3,000 feet below.

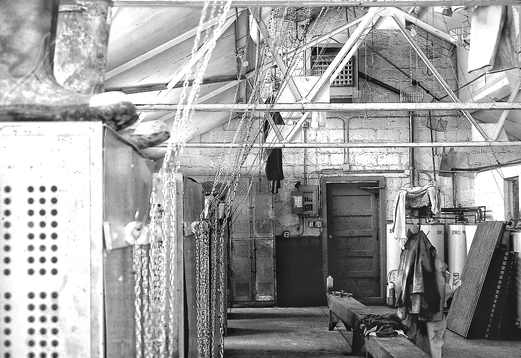

Ajax Change Room – Photo by Charles Clark ©, Click to Enlarge.

Ajax Change Room – Photo by Charles Clark ©, Click to Enlarge.

The miners would tease me and play jokes on me. I was the greenhorn. But after this initiation everything was fine. I was one of them. They showed me the best way to do the jobs I was told to do. They were always friendly and I believe they watched over me.

At lunch time we would sit on a plank in a little wider spot in the drift where we could stretch our feet. The miners were amazed at the amount of food I had in my lunch pail. My mother would fill the lunch pail with a sandwich or two, chips, an apple, Tupperware cups with tops that held jello or fruit cocktail or something else that had to be in a container, cookies or cake and a Coke. It was always full to the top. They offered to trade lunch pails. Once in a while my Mom would send extra cookies for the other miners.

One of the jobs I did was to shovel muck into the tram cars as they drove a drift. The bottom holes for dynamite were called lifters because the broken rock would be thrown back onto a thick metal plate. A square point shovel would slide on the plate so you could easily pick up a full shovel load and throw it into the tram car. When it was full I would push it back to a spur or the station and bring an empty tram car forward to fill.

A few years later they had mucking machines that would pick up the rock and dump it into the tram car attached to the rear of the mucking machine. When it was full I would push the tram car out and bring an empty one forward. After the operator got all the rock he could, he would move the mucking machine back to the spur and I would bring a tram car and clean up the loose rock. The miner would drill his holes, fill them with dynamite, light the fuse and we would go down the drift and around a corner and wait for the explosions. The miner would count each one to make sure each one went off. If it didn’t, it would be very dangerous trying to find the cap and the stick of dynamite. That was the end of the day and we would go to the surface allowing the dust to settle overnight.

We were paid for eight hours, portal to portal, from the time we got in the skip to go down and got out of the skip when we came up. Now on the surface, we would give our battery packs to a person who would recharge them for the next day. In the change room we would get out of our wet clothes, which everyone called “diggers,” and lower our clean clothes down to us that were on a metal ring with several hooks. Our wet diggers were hung on the hooks and pulled to the roof. The heat in the room would dry them.

Helping the miner in the stope and stope mucking were two jobs I did quite often. When helping the miner I did a variety of jobs. I would carry the dynamite and other equipment up the man way. I also tried to make the broken rock we stood on level, so we could lay a two by eight board flat on the surface. The miner would set the bottom of his drill on the board and when he turned it on to drill, the compressed air would push the stinger against the board and that would force the drill bit to cut into the rock.

He used three drill lengths, short, medium and long, which were two feet, 4 feet and 6 feet long. When he changed drill steel I would take the one he was using and hand him the next one. Each hole was six feet deep. There was a hole down the middle of the drill steel and the bit. Water came through the holes which eliminated the dust and cooled the bit. When he finished drilling, we would move our equipment to get it out of the way when he dynamited at the end of the day. The next morning we would start on the next section. Leveling, putting the board down, moving the hoses for the compressed air and water, getting the drill, drill steel, etc. and start drilling. To give us enough room to work, I would pull the rock out of the chute to lower the floor.

After the miner finished drilling the stope, stopping at the required distance from the level above, stope mucking began. A stope could have a number of chutes as they followed the gold vein. We would fill tram cars taking ore out of each chute as the miner moved down the stope. When enough ore had been pulled, we climbed up the man way and began moving the broken rock downward off the stope. The gold veins at Cripple Creek mines ran diagonally, so there was a slant to the rock face that some ore would hang up on and needed to be scraped off. Rock would stay on the stulls, timbers supporting the roof, and needed cleaning off. The routine was to pull rock out of the chutes and then go up and clean off the slant and stulls. This would take a while since some of the stopes were long following the vein and had many chutes.

The easiest job I did was to help when they were surveying to map out the mine. The man would put a marker in the top of the drift and my job was to hold my light behind the marker so he could see it.

Another time I went with a miner back into an older part of the mine that was larger than a drift. He used a jack hammer and drilled a number of holes in the bottom. Without water, the dust was so thick you could hardly see the hole. I shined my light on the hole so he could see where he was drilling. He blasted that area. The next day I was sent to the same place to clean it up. I filled the tram car, but didn’t realize my light was getting dimmer. I knew I better get out of there. I started pushing the tram car down the drift and hadn’t gone very far when my light went out. I was scared. I yelled and since I was in an unused part of the mine no one heard me. What would I do? After my heart rate slowed down, I told myself I could put my hand on the rock wall and slide my feet on the tracks. I tried that, but it wasn’t working very well. Then it dawned on me, I could push the tram car out. What an event. Black is really black underground. I found the work very interesting and challenging, but I wanted to go on for higher education.

In the fall of 1951, I went to Colorado University in Boulder for two years. In July 1953 I went into the Army for two years, and was stationed in Germany for 18 months of that tour. After being discharged, I came back to Cripple Creek and worked again that summer at the Ajax mine. The company was always good to put me on. I lost 40 pounds from hard work and sweat at the Ajax. This was enough to send me back to Colorado University for a different field of work.

We lived in Vetsville at the University and I went to school on the GI Bill for my service in the Army during the Korean War conflict.

At lunch time we would sit on a plank in a little wider spot in the drift where we could stretch our feet. The miners were amazed at the amount of food I had in my lunch pail. My mother would fill the lunch pail with a sandwich or two, chips, an apple, Tupperware cups with tops that held jello or fruit cocktail or something else that had to be in a container, cookies or cake and a Coke. It was always full to the top. They offered to trade lunch pails. Once in a while my Mom would send extra cookies for the other miners.

One of the jobs I did was to shovel muck into the tram cars as they drove a drift. The bottom holes for dynamite were called lifters because the broken rock would be thrown back onto a thick metal plate. A square point shovel would slide on the plate so you could easily pick up a full shovel load and throw it into the tram car. When it was full I would push it back to a spur or the station and bring an empty tram car forward to fill.

A few years later they had mucking machines that would pick up the rock and dump it into the tram car attached to the rear of the mucking machine. When it was full I would push the tram car out and bring an empty one forward. After the operator got all the rock he could, he would move the mucking machine back to the spur and I would bring a tram car and clean up the loose rock. The miner would drill his holes, fill them with dynamite, light the fuse and we would go down the drift and around a corner and wait for the explosions. The miner would count each one to make sure each one went off. If it didn’t, it would be very dangerous trying to find the cap and the stick of dynamite. That was the end of the day and we would go to the surface allowing the dust to settle overnight.

We were paid for eight hours, portal to portal, from the time we got in the skip to go down and got out of the skip when we came up. Now on the surface, we would give our battery packs to a person who would recharge them for the next day. In the change room we would get out of our wet clothes, which everyone called “diggers,” and lower our clean clothes down to us that were on a metal ring with several hooks. Our wet diggers were hung on the hooks and pulled to the roof. The heat in the room would dry them.

Helping the miner in the stope and stope mucking were two jobs I did quite often. When helping the miner I did a variety of jobs. I would carry the dynamite and other equipment up the man way. I also tried to make the broken rock we stood on level, so we could lay a two by eight board flat on the surface. The miner would set the bottom of his drill on the board and when he turned it on to drill, the compressed air would push the stinger against the board and that would force the drill bit to cut into the rock.

He used three drill lengths, short, medium and long, which were two feet, 4 feet and 6 feet long. When he changed drill steel I would take the one he was using and hand him the next one. Each hole was six feet deep. There was a hole down the middle of the drill steel and the bit. Water came through the holes which eliminated the dust and cooled the bit. When he finished drilling, we would move our equipment to get it out of the way when he dynamited at the end of the day. The next morning we would start on the next section. Leveling, putting the board down, moving the hoses for the compressed air and water, getting the drill, drill steel, etc. and start drilling. To give us enough room to work, I would pull the rock out of the chute to lower the floor.

After the miner finished drilling the stope, stopping at the required distance from the level above, stope mucking began. A stope could have a number of chutes as they followed the gold vein. We would fill tram cars taking ore out of each chute as the miner moved down the stope. When enough ore had been pulled, we climbed up the man way and began moving the broken rock downward off the stope. The gold veins at Cripple Creek mines ran diagonally, so there was a slant to the rock face that some ore would hang up on and needed to be scraped off. Rock would stay on the stulls, timbers supporting the roof, and needed cleaning off. The routine was to pull rock out of the chutes and then go up and clean off the slant and stulls. This would take a while since some of the stopes were long following the vein and had many chutes.

The easiest job I did was to help when they were surveying to map out the mine. The man would put a marker in the top of the drift and my job was to hold my light behind the marker so he could see it.

Another time I went with a miner back into an older part of the mine that was larger than a drift. He used a jack hammer and drilled a number of holes in the bottom. Without water, the dust was so thick you could hardly see the hole. I shined my light on the hole so he could see where he was drilling. He blasted that area. The next day I was sent to the same place to clean it up. I filled the tram car, but didn’t realize my light was getting dimmer. I knew I better get out of there. I started pushing the tram car down the drift and hadn’t gone very far when my light went out. I was scared. I yelled and since I was in an unused part of the mine no one heard me. What would I do? After my heart rate slowed down, I told myself I could put my hand on the rock wall and slide my feet on the tracks. I tried that, but it wasn’t working very well. Then it dawned on me, I could push the tram car out. What an event. Black is really black underground. I found the work very interesting and challenging, but I wanted to go on for higher education.

In the fall of 1951, I went to Colorado University in Boulder for two years. In July 1953 I went into the Army for two years, and was stationed in Germany for 18 months of that tour. After being discharged, I came back to Cripple Creek and worked again that summer at the Ajax mine. The company was always good to put me on. I lost 40 pounds from hard work and sweat at the Ajax. This was enough to send me back to Colorado University for a different field of work.

We lived in Vetsville at the University and I went to school on the GI Bill for my service in the Army during the Korean War conflict.

After working underground at the Cression & Ajax Mines, Myron House became Advertising Director for the Sterling Journal-Advocate Newspaper.

After working underground at the Cression & Ajax Mines, Myron House became Advertising Director for the Sterling Journal-Advocate Newspaper.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

The Memories of Myron House's Experiences Working Underground as a young man at the Cresson and Ajax Mines were enhanced with photos by Charles (Chuck) Clark and submitted in tandem with Chuck’s vignette about “A Day in the Life of a Miner” in May 2016.

Myron House graduated from Cripple Creek High School in 1951. After completing his studies in 1958 at the University of Colorado (which were interrupted by two years of service in the Army), Myron accepted a job in advertising with the Journal-Advocate Newspaper in Sterling, Colorado where he eventually retired in 1997 and lives today.

Myron married Rita Flanagan, who was from Victor. Rita's father was the butcher at the Olsen & Flanagan Grocery Store on Victor Avenue.

The Memories of Myron House's Experiences Working Underground as a young man at the Cresson and Ajax Mines were enhanced with photos by Charles (Chuck) Clark and submitted in tandem with Chuck’s vignette about “A Day in the Life of a Miner” in May 2016.

Myron House graduated from Cripple Creek High School in 1951. After completing his studies in 1958 at the University of Colorado (which were interrupted by two years of service in the Army), Myron accepted a job in advertising with the Journal-Advocate Newspaper in Sterling, Colorado where he eventually retired in 1997 and lives today.

Myron married Rita Flanagan, who was from Victor. Rita's father was the butcher at the Olsen & Flanagan Grocery Store on Victor Avenue.

THE PAST MATTERS. PASS IT ALONG.

The Next Generation Will Only Inherit What We Choose to Save and Make Accessible.

Please Share Your Memories and Family Connections to Victor & the World's Greatest Gold Camp by

Contacting Victor Heritage Society, PO Box 424, Victor, CO 80860 or e-mail [email protected].

The Next Generation Will Only Inherit What We Choose to Save and Make Accessible.

Please Share Your Memories and Family Connections to Victor & the World's Greatest Gold Camp by

Contacting Victor Heritage Society, PO Box 424, Victor, CO 80860 or e-mail [email protected].

VictorHeritageSociety.com

Copyright © 2023 Victor Heritage Society. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright © 2023 Victor Heritage Society. All Rights Reserved.