REFLECTIONS ON GOLDFIELD

By Carol E. Roberts, 1928-2003

In the 1870’s, several years before gold was found in the Cripple Creek Mining District, a forest fire raged through the area later known as Goldfield. Regrowth produced a volume of grass, wild flowers and raspberry bushes. Early settlers from as far away as Florissant came to pick the berries for canning and eating.

There was a summer cow camp near Victor Pass and the area was used as pasturage. Located in the valley between Big Bull Mountain to the east and Bull Hill on the west, Goldfield was platted by the Portland Town & Mineral Company, Inc. on August 4, 1894 with capital of $150,000 and 5 directors with offices in Denver.

Bull Hill and Bull Mountain were so named because of the type of ore found there. It came from the French word “bullous” meaning bubbly.

The city lies southwest to northeast with the numbered streets running east and west and those running north and south, the avenues. Most blocks consist of 40 lots, 25 X 125 feet, divided by 15-foot alleys and 50-foot wide streets. There were dozens of mining claims running over the area, so the lots were sold with surface rights only, which are defined as the top 25 feet. Many lots were available at $25 each.

The northern part of Goldfield was allotted to railroads for their yards and tracks. A reservoir was built near several natural springs in the area. Ditches were dug down the streets and then covered with board sidewalks. Thus, each lot had water available “to the door”. In 1900, a house and lot could be purchased for $100 - $150. Many of the houses were typical miner’s cabins, but there were also many fine houses of Victorian & French Provincial architecture. However, on a 25 foot lot, side windows didn’t exist, except for those homes on corner lots.

On April 11, 1895, the town of Goldfield’s first trustees met and delineated the offices for the City and the officers’ duties. John Easter was the mayor and John Plaserwood was clerk & recorder. Also, there was a town treasurer, attorney and marshall. Between April 11th and May 1st 1895, licenses were established for saloons, businesses and dogs. Ordinances were established against vagrancy and prostitution. There was a poll tax ordinance and an ordinance forming the fire department with a chief and an assistant chief. An ordinance made it illegal for boys to ride on the fire equipment or hang around the fire station.

May 8th brought forth a street commissioner. The town physician was in charge of the City “Pest House”, which was located near the Lillie Mine. It held transients who were contagious or people affected with tuberculosis. Albert Pheasants, an attendant there, was found to be too intoxicated to perform his duties and was thusly fired. The prisoners in the jail were also in the charge of the town physician. His fees were not to exceed $300 per year. The town engineer was in charge of streets, alleys, and sidewalks and was to receive $10 each day that he actually worked.

By 1896, wooden conduits were to be used to transport water for the citizens of Goldfield. A $30,000 bond was in effect for this project. In 1897, Goldfield gave permission for Victor to lay a water line through a part of the City of Goldfield. In early 1898, Goldfield made a deal with Victor to tap into this line to supply the City with water. In late 1898, the town of Independence was allowed to hook into Goldfield’s water supply for their citizens’ use.

Other interesting events occurred during the later years of the 90's. The town trustees were given permission to replace the Marshall if he were too drunk to work. Arc lights were brought to the town of Goldfield to light the streets. Telephone lines were added and there was a small pox epidemic. Ordinances were passed directing the city physicians to place a sign reading "SMALL POX HERE" on houses with people so afflicted. Scarlet fever and diphtheria were also to be posted.

By 1899, Goldfield had an evaluation of $240,855. By the following year it had grown to 3,000 people and was known as the “City of Beautiful Homes”. Residences were well cared for, yards were well attended to and people took pride in their properties (if only that were true today). There was a town scavenger who removed all trash and offensive materials from both the streets and alleys.

There were four schools and a city hall that was completed in 1898, complete with bell tower and bell. The bell is presently beside the Victor City Hall, but will be returned to its original “home” when the Goldfield City Hall restoration is farther along.

There were numerous churches of various denominations and there were ordinances against loud or profane language in public. Ladies had no fear in the streets except for the dirt which must have been murder on long, white dresses, especially when it was muddy! Public parades, picnics, band concerts and other similar functions were frequent. Downtown buildings were decorated on holidays with flags and buntings.

Street cars were available for people to travel to any town in the District for 5 cents. The tracks were laid in a large curve coming into Goldfield from the south, going east through Block 37, then south up a filled curve toward Summit Avenue. They continued behind the City Hall and cut back through north Goldfield toward the town of Independence. A lengthy agreement was signed by the City trustees with stringent laws stating that all utility poles put in for the electric street cars be painted black the first 8 feet and white to the top. Did Goldfield have long legged dogs?

This same ordinance was in effect all over the District and pictures from that time in Cripple Creek and Victor all show the white and black poles. Alas, there are none left in Goldfield, but you can see one by the Victor Elks building, one between Diamond and Victor Avenues on Fourth St., and a nice one in front of 309 Victor Ave.

By Carol E. Roberts, 1928-2003

In the 1870’s, several years before gold was found in the Cripple Creek Mining District, a forest fire raged through the area later known as Goldfield. Regrowth produced a volume of grass, wild flowers and raspberry bushes. Early settlers from as far away as Florissant came to pick the berries for canning and eating.

There was a summer cow camp near Victor Pass and the area was used as pasturage. Located in the valley between Big Bull Mountain to the east and Bull Hill on the west, Goldfield was platted by the Portland Town & Mineral Company, Inc. on August 4, 1894 with capital of $150,000 and 5 directors with offices in Denver.

Bull Hill and Bull Mountain were so named because of the type of ore found there. It came from the French word “bullous” meaning bubbly.

The city lies southwest to northeast with the numbered streets running east and west and those running north and south, the avenues. Most blocks consist of 40 lots, 25 X 125 feet, divided by 15-foot alleys and 50-foot wide streets. There were dozens of mining claims running over the area, so the lots were sold with surface rights only, which are defined as the top 25 feet. Many lots were available at $25 each.

The northern part of Goldfield was allotted to railroads for their yards and tracks. A reservoir was built near several natural springs in the area. Ditches were dug down the streets and then covered with board sidewalks. Thus, each lot had water available “to the door”. In 1900, a house and lot could be purchased for $100 - $150. Many of the houses were typical miner’s cabins, but there were also many fine houses of Victorian & French Provincial architecture. However, on a 25 foot lot, side windows didn’t exist, except for those homes on corner lots.

On April 11, 1895, the town of Goldfield’s first trustees met and delineated the offices for the City and the officers’ duties. John Easter was the mayor and John Plaserwood was clerk & recorder. Also, there was a town treasurer, attorney and marshall. Between April 11th and May 1st 1895, licenses were established for saloons, businesses and dogs. Ordinances were established against vagrancy and prostitution. There was a poll tax ordinance and an ordinance forming the fire department with a chief and an assistant chief. An ordinance made it illegal for boys to ride on the fire equipment or hang around the fire station.

May 8th brought forth a street commissioner. The town physician was in charge of the City “Pest House”, which was located near the Lillie Mine. It held transients who were contagious or people affected with tuberculosis. Albert Pheasants, an attendant there, was found to be too intoxicated to perform his duties and was thusly fired. The prisoners in the jail were also in the charge of the town physician. His fees were not to exceed $300 per year. The town engineer was in charge of streets, alleys, and sidewalks and was to receive $10 each day that he actually worked.

By 1896, wooden conduits were to be used to transport water for the citizens of Goldfield. A $30,000 bond was in effect for this project. In 1897, Goldfield gave permission for Victor to lay a water line through a part of the City of Goldfield. In early 1898, Goldfield made a deal with Victor to tap into this line to supply the City with water. In late 1898, the town of Independence was allowed to hook into Goldfield’s water supply for their citizens’ use.

Other interesting events occurred during the later years of the 90's. The town trustees were given permission to replace the Marshall if he were too drunk to work. Arc lights were brought to the town of Goldfield to light the streets. Telephone lines were added and there was a small pox epidemic. Ordinances were passed directing the city physicians to place a sign reading "SMALL POX HERE" on houses with people so afflicted. Scarlet fever and diphtheria were also to be posted.

By 1899, Goldfield had an evaluation of $240,855. By the following year it had grown to 3,000 people and was known as the “City of Beautiful Homes”. Residences were well cared for, yards were well attended to and people took pride in their properties (if only that were true today). There was a town scavenger who removed all trash and offensive materials from both the streets and alleys.

There were four schools and a city hall that was completed in 1898, complete with bell tower and bell. The bell is presently beside the Victor City Hall, but will be returned to its original “home” when the Goldfield City Hall restoration is farther along.

There were numerous churches of various denominations and there were ordinances against loud or profane language in public. Ladies had no fear in the streets except for the dirt which must have been murder on long, white dresses, especially when it was muddy! Public parades, picnics, band concerts and other similar functions were frequent. Downtown buildings were decorated on holidays with flags and buntings.

Street cars were available for people to travel to any town in the District for 5 cents. The tracks were laid in a large curve coming into Goldfield from the south, going east through Block 37, then south up a filled curve toward Summit Avenue. They continued behind the City Hall and cut back through north Goldfield toward the town of Independence. A lengthy agreement was signed by the City trustees with stringent laws stating that all utility poles put in for the electric street cars be painted black the first 8 feet and white to the top. Did Goldfield have long legged dogs?

This same ordinance was in effect all over the District and pictures from that time in Cripple Creek and Victor all show the white and black poles. Alas, there are none left in Goldfield, but you can see one by the Victor Elks building, one between Diamond and Victor Avenues on Fourth St., and a nice one in front of 309 Victor Ave.

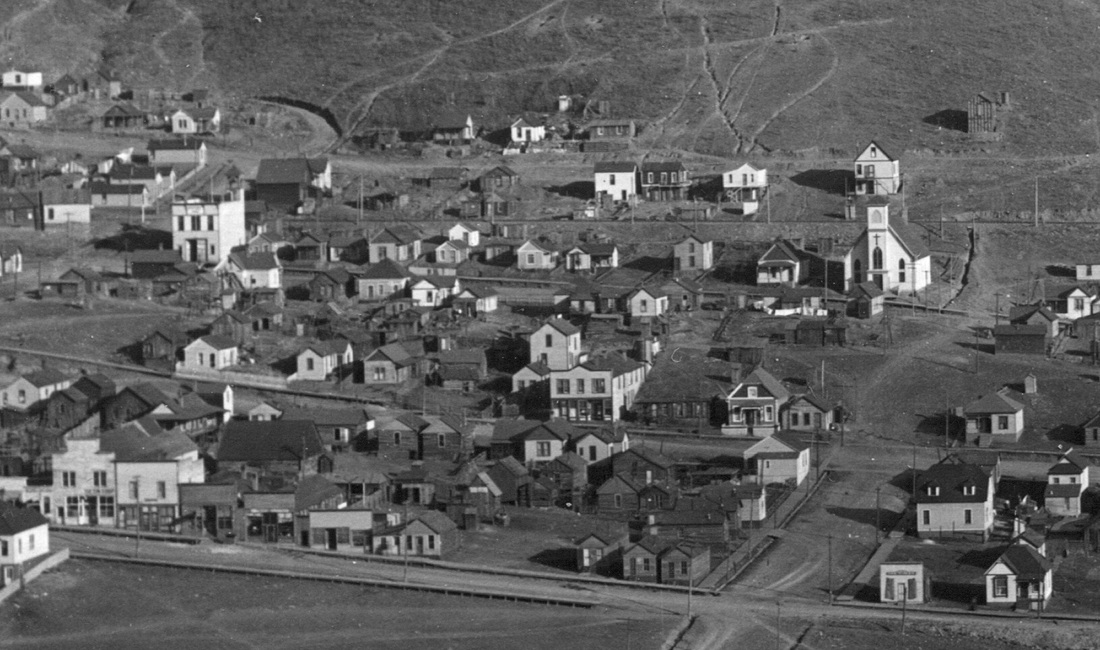

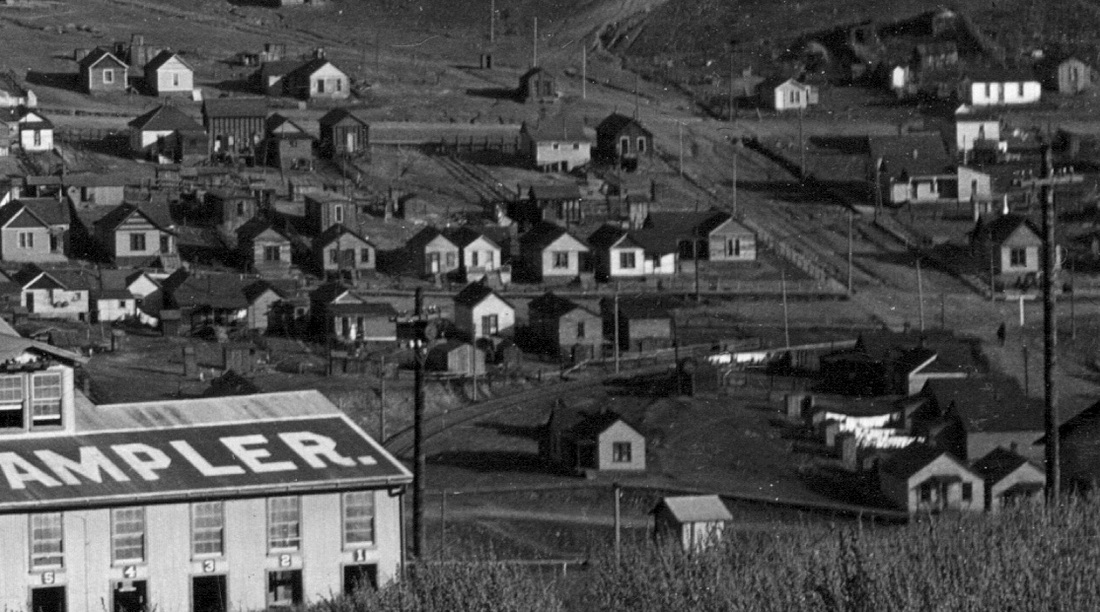

1903 View of Goldfield from Battle Mountain.

1903 View of Goldfield from Battle Mountain.

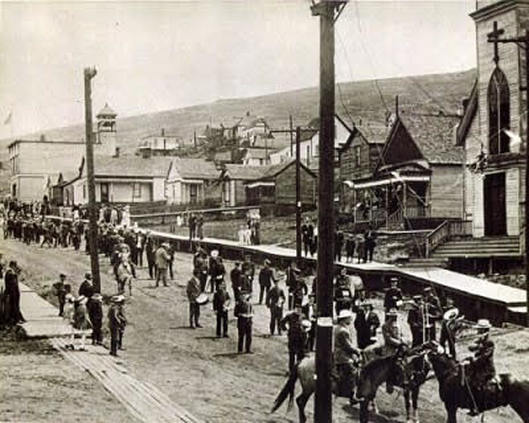

Goldfield street and elevated sidewalk passing in front of the City Hall / Fire Station (far left) and the Roman Catholic Church (far right) where a band is gathered. Photo contributed by LaJean Greeson.

Goldfield street and elevated sidewalk passing in front of the City Hall / Fire Station (far left) and the Roman Catholic Church (far right) where a band is gathered. Photo contributed by LaJean Greeson.

Some of the early pictures of Goldfield show a small building to wait in, out of the weather, for street cars at the corner of Independence and 12th Streets.

Horses and carriages were not to travel at speeds in excess of 6 mph. No animals were allowed to run loose in the city limits. Each household was responsible for the upkeep of the sidewalks in front of their homes. If they didn’t keep them in repair, the city would repair them and assess the homeowner. Keeping the nails pounded down was a must. One advantage of these wooden sidewalks, in later years when they were disappearing or already gone, was that you could search the ditches after a heavy rain storm and find money that had been dropped years before. Many a child would search those ditches and sometimes even find gold coins.

Goldfield had a fire department in the City Hall. They had a hand-pulled hose cart and a horse drawn ladder truck, which are on display in the Lowell Thomas Museum in Victor. The fire chief’s hat is in the Cripple Creek Museum. Contests were often held between fire departments to see how fast a team of men could pull a hose cart and hook up the hoses. Goldfield had fire hydrants on each street corner, because they were connected to the wooden pipe lines. In later years, many would break and leak. In 1975, I received permission from the Victor water department to paint the working hydrants in Goldfield. I was amazed at the beautiful designs of these plugs. They were as ornate as a capitol building in most states.

Several years ago, Nell Anderson, who was then the Clerk of the Teller County Court, found in an unused vault in the Court House a cache of gold ore and the original hand-written city ordinances of Goldfield. These ordinances were written in beautiful penmanship in a huge, old fashioned ledger. The Internal Revenue Service claimed the ore the very same day it was found. The ore and ordinance book had been used in a hi-grading suit many years ago. The IRS was terribly disappointed to find out that the ore was of low grade. It had been switched for hi-grade, which was the reason for the law suit in the first place. Until the time that Goldfield got a typewriter, the ordinances were hand-written.

During the First World War, gold mines were closed so that miners could go work in essential metal mines. Many miners from this area were sent to mine tungsten near Nederland, Colorado.

About this time, oil was booming in Casper, Wyoming and there was a shortage of houses. An entrepreneur came through and loaded many of the houses from Goldfield on to flat cars to be shipped to Casper where they ended up on the “Sand Bar” area in Casper, a red light district. When some people came back after WWI, their houses weren’t here.

Goldfield never had a big fire like Victor and Cripple Creek. As the town shrank, many houses were torn down to avoid paying taxes or by a neighbor for the wood in them. For years and years, lots could be had for back taxes paid to the County Treasurer.

Horses and carriages were not to travel at speeds in excess of 6 mph. No animals were allowed to run loose in the city limits. Each household was responsible for the upkeep of the sidewalks in front of their homes. If they didn’t keep them in repair, the city would repair them and assess the homeowner. Keeping the nails pounded down was a must. One advantage of these wooden sidewalks, in later years when they were disappearing or already gone, was that you could search the ditches after a heavy rain storm and find money that had been dropped years before. Many a child would search those ditches and sometimes even find gold coins.

Goldfield had a fire department in the City Hall. They had a hand-pulled hose cart and a horse drawn ladder truck, which are on display in the Lowell Thomas Museum in Victor. The fire chief’s hat is in the Cripple Creek Museum. Contests were often held between fire departments to see how fast a team of men could pull a hose cart and hook up the hoses. Goldfield had fire hydrants on each street corner, because they were connected to the wooden pipe lines. In later years, many would break and leak. In 1975, I received permission from the Victor water department to paint the working hydrants in Goldfield. I was amazed at the beautiful designs of these plugs. They were as ornate as a capitol building in most states.

Several years ago, Nell Anderson, who was then the Clerk of the Teller County Court, found in an unused vault in the Court House a cache of gold ore and the original hand-written city ordinances of Goldfield. These ordinances were written in beautiful penmanship in a huge, old fashioned ledger. The Internal Revenue Service claimed the ore the very same day it was found. The ore and ordinance book had been used in a hi-grading suit many years ago. The IRS was terribly disappointed to find out that the ore was of low grade. It had been switched for hi-grade, which was the reason for the law suit in the first place. Until the time that Goldfield got a typewriter, the ordinances were hand-written.

During the First World War, gold mines were closed so that miners could go work in essential metal mines. Many miners from this area were sent to mine tungsten near Nederland, Colorado.

About this time, oil was booming in Casper, Wyoming and there was a shortage of houses. An entrepreneur came through and loaded many of the houses from Goldfield on to flat cars to be shipped to Casper where they ended up on the “Sand Bar” area in Casper, a red light district. When some people came back after WWI, their houses weren’t here.

Goldfield never had a big fire like Victor and Cripple Creek. As the town shrank, many houses were torn down to avoid paying taxes or by a neighbor for the wood in them. For years and years, lots could be had for back taxes paid to the County Treasurer.

Memorial Day 1964, we bought a fixer-upper on two and a half lots. My first impression was "what a dump".

Memorial Day 1964, we bought a fixer-upper on two and a half lots. My first impression was "what a dump".

In 1964, we bought two and a half lots for $37.50. An entire block was available for $175. There were many pieces of lots on the tax rolls because a lot may have been divided up for the children of owners who had died.

Some miners dug shafts in their back yards. Some would call these mines and try to sell stock in them. Jim Gugle, who lived at 1130 Independence Avenue for years, mowed the grass in his back lots one day. The next day when he went out, a shaft had opened up in the night where he had mowed the day before. The shaft was about 80 feet deep. As Jim loved to mix concrete, he built Goldfield’s first and only cement goldfish pond, complete with statue and blue painted sides and bottom. It was a lovely blue, as I bought him the paint.

My introduction to Goldfield was an invitation to visit on Memorial Day weekend in 1964 at Maida Campbell’s, whose parents were patients of mine in Denver. Maida owned the parish house of the Methodist Church on Victor Avenue. At that time, many of the houses that were here had been abandoned by the people who were forced to move elsewhere when the mines closed. Other people had entered these houses and stolen what they wanted. Lying all over the ground were numerous items such as pots, pans, books, boots, wire and pieces of glass and china. My first impression was, “My God! What a dump!” Over the years, tourists picked up many of the items to make planters or whatever.

Some miners dug shafts in their back yards. Some would call these mines and try to sell stock in them. Jim Gugle, who lived at 1130 Independence Avenue for years, mowed the grass in his back lots one day. The next day when he went out, a shaft had opened up in the night where he had mowed the day before. The shaft was about 80 feet deep. As Jim loved to mix concrete, he built Goldfield’s first and only cement goldfish pond, complete with statue and blue painted sides and bottom. It was a lovely blue, as I bought him the paint.

My introduction to Goldfield was an invitation to visit on Memorial Day weekend in 1964 at Maida Campbell’s, whose parents were patients of mine in Denver. Maida owned the parish house of the Methodist Church on Victor Avenue. At that time, many of the houses that were here had been abandoned by the people who were forced to move elsewhere when the mines closed. Other people had entered these houses and stolen what they wanted. Lying all over the ground were numerous items such as pots, pans, books, boots, wire and pieces of glass and china. My first impression was, “My God! What a dump!” Over the years, tourists picked up many of the items to make planters or whatever.

By July 4, 1965, we were "painting and repairing". What a transformation resulted from many phases of the long, arduous restoration project. More work and several additions to the home at 1125 Independence Ave followed.

By July 4, 1965, we were "painting and repairing". What a transformation resulted from many phases of the long, arduous restoration project. More work and several additions to the home at 1125 Independence Ave followed.

Maida showed us some property that was available for "fix-up" When I first saw the house, I couldn't help but wonder how many had lain in there and died of the "galloping consumption".

By the 4th of July, we were busy painting and repairing. Electricity and water had been connected and the stove was providing us warmth and also a means of preparing hot foods; that is, after we figured out how to work the drafts. The one in the kitchen was a Monarch range and the parlor stove was a Black & Germer with lots of nickel and a loving cup.

By the 4th of July, we were busy painting and repairing. Electricity and water had been connected and the stove was providing us warmth and also a means of preparing hot foods; that is, after we figured out how to work the drafts. The one in the kitchen was a Monarch range and the parlor stove was a Black & Germer with lots of nickel and a loving cup.

1125 Independence Ave, Goldfield after Carol Roberts and Barbara Doop completed many phases of restoration that included adding a covered porch (to the left), and a gabled wing and adjoining garage (to the right).

1125 Independence Ave, Goldfield after Carol Roberts and Barbara Doop completed many phases of restoration that included adding a covered porch (to the left), and a gabled wing and adjoining garage (to the right).

Our house at 1125 Independence Avenue was a polling place for elections held in 1904. A story is told about two miners sitting across the street near a wooden fence. A deputy sheriff named James Warford came along and told them to move. They continued sitting so Warford pulled out his gun and killed both of them with shots to the back. Warford was arrested, released, and rearrested—but his charges were eventually dropped.

In 1912, Warford was found dead on the slope of Battle Mountain. He had been shot through the head and heart by four .45 caliber bullets, two .38 caliber bullets and one .32 caliber bullet. He had also been beaten. Nobody ever found out who did it.

*****

One day I had guests visiting from Denver. I was in the kitchen when someone knocked on the door. My guest opened the door and let the couple in that were knocking. I hurried out of the kitchen and to the front door. This fellow said, “Hello, My name is Bill Jones and I was born here.” “Won’t you come in and sit down!” I said.

His grandfather’s name was Garnet Hoskins and was a miner; mostly at the Vindicator. Bill’s mother was living with her parents at the time, and Bill was born in 1915 in the smaller bedroom that we had made into a bathroom. Bill lived in our house for many years and described the wall paper exactly as it had been in that bedroom.

Bill was going into the Navy during WWII. The order to cease mining had been given by the government and Garn was helping to close the mine. Bill said his granddad usually had some sticks of dynamite in his pocket. While he was on a level in the mine that had not been used for a long time, he noticed three holes that had never been shot. So Garn put in his dynamite and blasted away. When the dust settled, he found a beautiful hi-grade vein exposed. He covered up the evidence and brought home some great samples. He said to Bill, “When you get back from the Navy, we’ll take a lease on this and make some money." Bill replied, “Don’t you think you’d better tell me where this vein is?” “No,” said Garn. “When you get out, I’ll be ready to mine with you.” So Bill went off to war and Garn went to Denver to live with a daughter.

During that time, Garn would come back to Victor now and then to have a drink with his buddies. One day, in the Gold Coin Bar, his daughter said, “Dad, we ought to get going.” “Let me have one more drink,” responded Garn. Garn believed a true man would die with his boots on and a shot of whiskey in his throat. He took his shot glass, emptied it and was going to follow it up with a beer chaser, but he kept right on going over backwards and was dead on the floor. He had died like a man.

When Bill got out of the Navy, he had no idea where to find that vein in the Vindicator. Instead, he went to college and became a stock broker. Of the house he had been born in, Bill said he had seen the house when it was at its worst and was so surprised to see it had been fixed up and people living in it now.

Several years later, while working for a mining company, I found Garn Hoskin’s payroll records. The most he ever made was $4.50 per day.

*****

Mrs. Alfred Givings owned our house in 1897. At that time it was located two lots to the south. When the railroad was to be brought through Goldfield, her house was in the way. The railroad company moved her house to its present location and paid her $20 for the trouble. At that time, the present kitchen and second bedroom were added to the back of the basic house.

During the strike years of 1903 and 1904, apparently Alfred was a member of the Western Federation of Miners. He was one of the 226 miners shipped out of the County on flat cars and told never to return. Several years ago, while putting in a new window where another had been, a note was found down behind the window sill that said Alfred was in Ruleton, Kansas. Ruleton was a railroad town on the west edge of Kansas. It has been reported that he and his family ended up in Goldfield, Nevada. I hope he had a good life.

According to the 1905 District directory, the Givings had a daughter named Cynthia and a son named Robert. The directory also said that Joseph Forselle (a miner at the Independence) and Pat Kelly (a miner at the Deadwood) lived at the REAR of 1125 Independence Avenue. Old photographs show that only a small shed was at the back of this property. When we purchased it, only a horse shed in bad disrepair was located there. But I guess anything was possible in those early mining days.

*****

Walking around the hills and streets of Goldfield town was an excitement for me in 1964—an excitement that has never really dulled even to this day. I got hooked on finding out all I could about the area and I have an ongoing relationship with this town to learn even more.

*****

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Carol E. Roberts was born and educated in Indiana. She came West to stay in 1954. As a medical technologist, she worked in a small hospital and clinic in Wyoming, and then moved to Denver to be an operator/owner of a laboratory there. In the late 60’s, most weekends were spent renovating 1125 Independence Ave., in Goldfield, Colorado.

After a bout with cancer and a desire to leave the city, she moved permanently to Goldfield and with a partner, bought “Harshie’s Corner” building at 300 Victor Ave. in Victor, Colorado. The Corner Store, the Quart House Liquor Store, and rooms to rent upstairs were opened to the public in 1973. After selling the businesses and building in 1979, Carol worked as the curator of Victor’s Museum.

During the 1980’s and until her retirement in June of 1992, she worked as an assayer of precious metals for several different mining companies that came into the Cripple Creek/Victor Mining District during those years. Carol Robert's service to the Cripple Creek & Victor Mining Company was recognized in 1997 when the new $2.3 million Technical Services Building was named in her honor. Being a history buff was one thread that ran though her life no matter what the year.

Submitted by Barbara Doop, September 2014.

In 1912, Warford was found dead on the slope of Battle Mountain. He had been shot through the head and heart by four .45 caliber bullets, two .38 caliber bullets and one .32 caliber bullet. He had also been beaten. Nobody ever found out who did it.

*****

One day I had guests visiting from Denver. I was in the kitchen when someone knocked on the door. My guest opened the door and let the couple in that were knocking. I hurried out of the kitchen and to the front door. This fellow said, “Hello, My name is Bill Jones and I was born here.” “Won’t you come in and sit down!” I said.

His grandfather’s name was Garnet Hoskins and was a miner; mostly at the Vindicator. Bill’s mother was living with her parents at the time, and Bill was born in 1915 in the smaller bedroom that we had made into a bathroom. Bill lived in our house for many years and described the wall paper exactly as it had been in that bedroom.

Bill was going into the Navy during WWII. The order to cease mining had been given by the government and Garn was helping to close the mine. Bill said his granddad usually had some sticks of dynamite in his pocket. While he was on a level in the mine that had not been used for a long time, he noticed three holes that had never been shot. So Garn put in his dynamite and blasted away. When the dust settled, he found a beautiful hi-grade vein exposed. He covered up the evidence and brought home some great samples. He said to Bill, “When you get back from the Navy, we’ll take a lease on this and make some money." Bill replied, “Don’t you think you’d better tell me where this vein is?” “No,” said Garn. “When you get out, I’ll be ready to mine with you.” So Bill went off to war and Garn went to Denver to live with a daughter.

During that time, Garn would come back to Victor now and then to have a drink with his buddies. One day, in the Gold Coin Bar, his daughter said, “Dad, we ought to get going.” “Let me have one more drink,” responded Garn. Garn believed a true man would die with his boots on and a shot of whiskey in his throat. He took his shot glass, emptied it and was going to follow it up with a beer chaser, but he kept right on going over backwards and was dead on the floor. He had died like a man.

When Bill got out of the Navy, he had no idea where to find that vein in the Vindicator. Instead, he went to college and became a stock broker. Of the house he had been born in, Bill said he had seen the house when it was at its worst and was so surprised to see it had been fixed up and people living in it now.

Several years later, while working for a mining company, I found Garn Hoskin’s payroll records. The most he ever made was $4.50 per day.

*****

Mrs. Alfred Givings owned our house in 1897. At that time it was located two lots to the south. When the railroad was to be brought through Goldfield, her house was in the way. The railroad company moved her house to its present location and paid her $20 for the trouble. At that time, the present kitchen and second bedroom were added to the back of the basic house.

During the strike years of 1903 and 1904, apparently Alfred was a member of the Western Federation of Miners. He was one of the 226 miners shipped out of the County on flat cars and told never to return. Several years ago, while putting in a new window where another had been, a note was found down behind the window sill that said Alfred was in Ruleton, Kansas. Ruleton was a railroad town on the west edge of Kansas. It has been reported that he and his family ended up in Goldfield, Nevada. I hope he had a good life.

According to the 1905 District directory, the Givings had a daughter named Cynthia and a son named Robert. The directory also said that Joseph Forselle (a miner at the Independence) and Pat Kelly (a miner at the Deadwood) lived at the REAR of 1125 Independence Avenue. Old photographs show that only a small shed was at the back of this property. When we purchased it, only a horse shed in bad disrepair was located there. But I guess anything was possible in those early mining days.

*****

Walking around the hills and streets of Goldfield town was an excitement for me in 1964—an excitement that has never really dulled even to this day. I got hooked on finding out all I could about the area and I have an ongoing relationship with this town to learn even more.

*****

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Carol E. Roberts was born and educated in Indiana. She came West to stay in 1954. As a medical technologist, she worked in a small hospital and clinic in Wyoming, and then moved to Denver to be an operator/owner of a laboratory there. In the late 60’s, most weekends were spent renovating 1125 Independence Ave., in Goldfield, Colorado.

After a bout with cancer and a desire to leave the city, she moved permanently to Goldfield and with a partner, bought “Harshie’s Corner” building at 300 Victor Ave. in Victor, Colorado. The Corner Store, the Quart House Liquor Store, and rooms to rent upstairs were opened to the public in 1973. After selling the businesses and building in 1979, Carol worked as the curator of Victor’s Museum.

During the 1980’s and until her retirement in June of 1992, she worked as an assayer of precious metals for several different mining companies that came into the Cripple Creek/Victor Mining District during those years. Carol Robert's service to the Cripple Creek & Victor Mining Company was recognized in 1997 when the new $2.3 million Technical Services Building was named in her honor. Being a history buff was one thread that ran though her life no matter what the year.

Submitted by Barbara Doop, September 2014.

THE PAST MATTERS. PASS IT ALONG.

The Next Generation Will Only Inherit What We Choose to Save and Make Accessible.

Please Share Your Memories and Family Connections to Victor & the World's Greatest Gold Camp

By Contacting Victor Heritage Society, PO Box 424, Victor, CO 80860 or e-mail [email protected].

The Next Generation Will Only Inherit What We Choose to Save and Make Accessible.

Please Share Your Memories and Family Connections to Victor & the World's Greatest Gold Camp

By Contacting Victor Heritage Society, PO Box 424, Victor, CO 80860 or e-mail [email protected].

VictorHeritageSociety.com

Copyright © 2023 Victor Heritage Society. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright © 2023 Victor Heritage Society. All Rights Reserved.