Lulu Ella Manson--before marriage to Harry Gordon Moore in 1893.

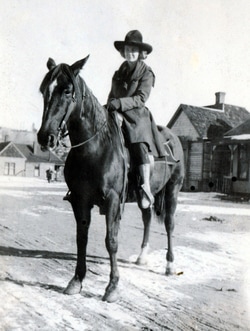

Lulu Ella Manson--before marriage to Harry Gordon Moore in 1893.

MEMORIES OF LULU ELLA MANSON & HARRY GORDON MOORE

As Recalled in Letters Written by Gertrude Moore McGowan (daughter) &

Submitted by Nancy McGowan Galbraith (granddaughter).

My father, Harry Gordon Moore, was born in Pennsylvania on August 14, 1870. Before moving to Denver with his young daughter by a first marriage, he was a school teacher and also had a Land Office Business in Nebraska.

My mother, Lulu Ella Manson, was born in Boston, Massachusetts on November 27, 1872 and moved to Denver with her parents at age 10. Her father had a small bakery known for a Saturday special—baked beans and Boston brown bread. Her parents separated and, after eighth grade, Mother became a milliner’s apprentice.

My mother was doing millinery work when she met my father who was a wholesale grocery salesman. He was divorced from his first wife and his daughter, Pearl, was living with his parents.

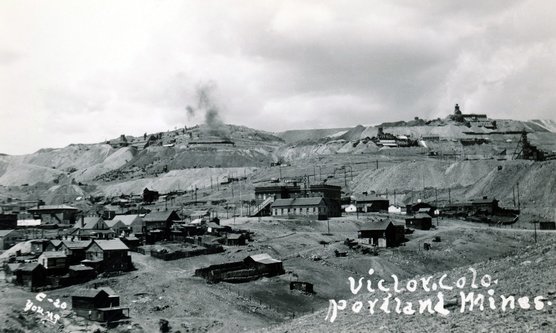

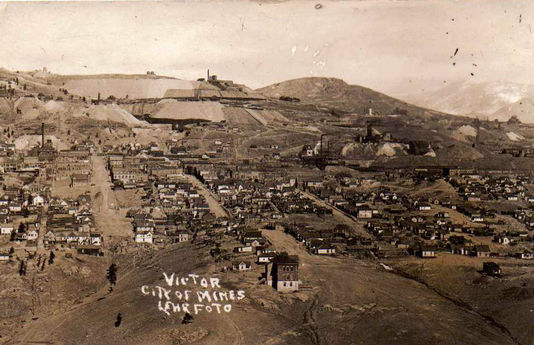

Lulu Ella Manson and Harry Gordon Moore were married in Denver on December 23, 1893. Soon after, in 1894, they moved to Victor, Colorado. It was a boomtown then and I suppose the idea of making a fortune seemed good.

In Victor their family eventually grew to include Pearl Louise (b 1891, from my father’s first marriage, d 1942) and Victor Harry (b 1896, d 1975), Howard Manson (b 1899, d 1921), William Hamilton (b 1902, d 1905), Wallace Gordon (b 1903, d 1988), Gertrude Clara (b 1905, d 1992), John Armstrong (b 1907, d 1919), Edward Alfred (b 1909, d 1972), and Isa Elizabeth (b 1920, d 1990).

Living on South Third

I know little about what life was like in Victor when my parents first came there in 1894. I do remember Mother saying that they had to buy water by the barrel, but I don’t know whether they had electricity and a telephone in the house.

The family first lived in a little house on South Third Street where Victor (their first child) was born. The family probably still lived on South Third when William died in 1905 of bronchial pneumonia at age 3 (a few months before I was born).

As Recalled in Letters Written by Gertrude Moore McGowan (daughter) &

Submitted by Nancy McGowan Galbraith (granddaughter).

My father, Harry Gordon Moore, was born in Pennsylvania on August 14, 1870. Before moving to Denver with his young daughter by a first marriage, he was a school teacher and also had a Land Office Business in Nebraska.

My mother, Lulu Ella Manson, was born in Boston, Massachusetts on November 27, 1872 and moved to Denver with her parents at age 10. Her father had a small bakery known for a Saturday special—baked beans and Boston brown bread. Her parents separated and, after eighth grade, Mother became a milliner’s apprentice.

My mother was doing millinery work when she met my father who was a wholesale grocery salesman. He was divorced from his first wife and his daughter, Pearl, was living with his parents.

Lulu Ella Manson and Harry Gordon Moore were married in Denver on December 23, 1893. Soon after, in 1894, they moved to Victor, Colorado. It was a boomtown then and I suppose the idea of making a fortune seemed good.

In Victor their family eventually grew to include Pearl Louise (b 1891, from my father’s first marriage, d 1942) and Victor Harry (b 1896, d 1975), Howard Manson (b 1899, d 1921), William Hamilton (b 1902, d 1905), Wallace Gordon (b 1903, d 1988), Gertrude Clara (b 1905, d 1992), John Armstrong (b 1907, d 1919), Edward Alfred (b 1909, d 1972), and Isa Elizabeth (b 1920, d 1990).

Living on South Third

I know little about what life was like in Victor when my parents first came there in 1894. I do remember Mother saying that they had to buy water by the barrel, but I don’t know whether they had electricity and a telephone in the house.

The family first lived in a little house on South Third Street where Victor (their first child) was born. The family probably still lived on South Third when William died in 1905 of bronchial pneumonia at age 3 (a few months before I was born).

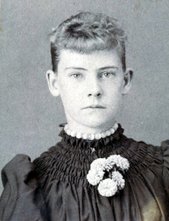

No photo of Father’s store on S 3rd St has been found. This photo shows “Simonton-Moore Merc. Co.” signs on a street-level storefront of the Western Federation of Miners Union Hall located on N 4th St. The photo was taken after the second-story offices & meeting hall for the WFM Union were wrecked and occupied by the Militia on June 7, 1904.

No photo of Father’s store on S 3rd St has been found. This photo shows “Simonton-Moore Merc. Co.” signs on a street-level storefront of the Western Federation of Miners Union Hall located on N 4th St. The photo was taken after the second-story offices & meeting hall for the WFM Union were wrecked and occupied by the Militia on June 7, 1904.

Father was involved in mining as a “leaser” and also had a grocery business called Simonton and Moore Mercantile, in partnership with one or two other men. It was located on South Third where Zitniks eventually had their store. I think previously he and his partner had a store on the corner of Third and Portland. As I recall Mother telling it, Father was cheated out of his interest in the store by his partners, as he was not a good businessman and drank too much to be aware of what was going on.

My father, Harry Gordon Moore (b 1870, d 1932), served as Captain in the Colorado Militia which was called to fight the miners unions in 1903-04. It was pretty bloody and took awhile, but finally the unions were ousted for good.

My father, Harry Gordon Moore (b 1870, d 1932), served as Captain in the Colorado Militia which was called to fight the miners unions in 1903-04. It was pretty bloody and took awhile, but finally the unions were ousted for good.

A strike was going on in the early years of this century [1903-04] and my father was a Captain in the State Militia which was sent in to prevent violence. There was violence—a bombing of the Independence Mine shaft as the night shift was coming off, and the train depot at the town of Independence was also blown up. The details are among some of the old books and papers I had concerning that time.

Clara (wife of my brother Victor) told me that at the time a neighbor saw some man going under our house and when my father investigated he found some sticks of dynamite. Somebody evidently was planning to kill him. So he decided that to protect the family, he had better move up town until things settled down. I guess he thought nobody would try to hurt the family, just him. That was before I was born. Even when I was grown and married, there were some of the older people in Victor who had no use for any of the Moore family on account of my father’s part in the strike. The strike organizers were a lawless gang and had to be stopped, but it had the effect of keeping unions out of the District for all time, which kept wages low.

Clara (wife of my brother Victor) told me that at the time a neighbor saw some man going under our house and when my father investigated he found some sticks of dynamite. Somebody evidently was planning to kill him. So he decided that to protect the family, he had better move up town until things settled down. I guess he thought nobody would try to hurt the family, just him. That was before I was born. Even when I was grown and married, there were some of the older people in Victor who had no use for any of the Moore family on account of my father’s part in the strike. The strike organizers were a lawless gang and had to be stopped, but it had the effect of keeping unions out of the District for all time, which kept wages low.

Stratonia House

In 1905 the family moved to a big white house owned by the Stratton Estate where I was born on July 22nd. I remember no details other than the house had a “modern” bathroom with an inside toilet (a rare luxury in those days) and a big yard. It was located east of Victor in a place called Stratonia (later referred to as the slimes dump when a gold processing mill was eventually built there).

I don’t know how it happened that we lived in that house. There must have been some business connection between my father and the Stratton Estate. I suppose Father knew Winfield Stratton, owner of the Independence Mine, since both were there in the 1890s. [Stratton died in 1902.]

In the yard of the Stratton house there was also a small house where an Englishman and his wife, Mr. and Mrs. Owen Johnson, lived. She and Mother were life-long friends. They had no children and she adored Wallace, who was a pretty, curly-haired little boy who loved to visit her, perhaps for the cookies she always had on hand.

In 1905 the family moved to a big white house owned by the Stratton Estate where I was born on July 22nd. I remember no details other than the house had a “modern” bathroom with an inside toilet (a rare luxury in those days) and a big yard. It was located east of Victor in a place called Stratonia (later referred to as the slimes dump when a gold processing mill was eventually built there).

I don’t know how it happened that we lived in that house. There must have been some business connection between my father and the Stratton Estate. I suppose Father knew Winfield Stratton, owner of the Independence Mine, since both were there in the 1890s. [Stratton died in 1902.]

In the yard of the Stratton house there was also a small house where an Englishman and his wife, Mr. and Mrs. Owen Johnson, lived. She and Mother were life-long friends. They had no children and she adored Wallace, who was a pretty, curly-haired little boy who loved to visit her, perhaps for the cookies she always had on hand.

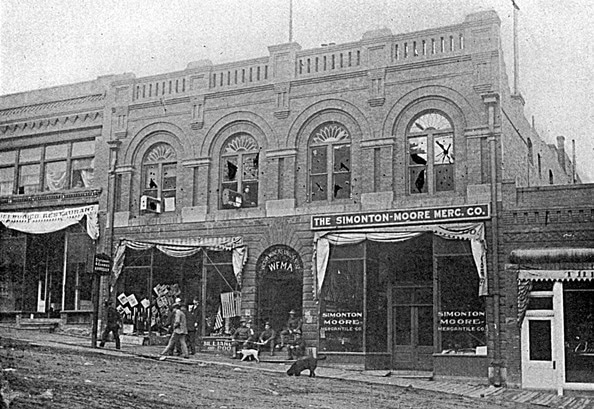

Moore children (about 1910-11) after moving from Stratonia house to 509 S 3rd Street in Victor . Back--Wallace (b 1903), Howard (b 1899). Front--John (b 1907), Edward (b 1909), Gertrude (b 1905).

Moore children (about 1910-11) after moving from Stratonia house to 509 S 3rd Street in Victor . Back--Wallace (b 1903), Howard (b 1899). Front--John (b 1907), Edward (b 1909), Gertrude (b 1905).

Return to South Third

In 1910 a change in our finances obliged us to move back to South Third. As long as I can remember, Father was a miner (leaser). I believe his grocery business was lost (gambled away) before we moved back to South Third Street. At one time Father also had an office uptown in what became the Post Office building, but I do not know what he did there.

I was about five years old and Ed about one year old at that time. About all I remember about the move was being allowed to ride on the big moving wagon, seated on one of our big leather chairs. The big Colorado Trading & Transfer Company coal wagons, hauled by huge horses, were the only means of transportation.

The place we moved into was two small houses (at 507 and 509 S 3rd St) joined together by a door-wide passage with a step up. Electricity and cold water piped into a sink with a drain emptying into the yard by the back stairs were the only modern features. The toilet (my mother insisted that “closet” was the correct word) was at the end of the yard in back of 509. The wood and coal shed was in back of 507. This place on South Third where we lived for the next ten years was a real come-down for the ones of the family who were old enough to realize the situation. A telephone (probably the only one on the block) was our one luxury.

In the main house (509) there was a big kitchen, a medium dining room, a living room, and one tiny bedroom which was Pearl’s. All heat was from coal and wood stoves.

There was always a fire in the kitchen stove which had a reservoir. “Fill the reservoir” and “fill the tea kettle” were constant warnings. With no hot water available as it is now by turning a faucet, having a kettle of hot water available was important; and to leave a teakettle empty on the hot stove was a condition not to be tolerated.

In the kitchen we had a large table which was Mother’s worktable (since there were no counters) as well as our dining table for breakfasts and lunches. There was a plain, unadorned sink with a mirror above it. I can remember looking forward to the day when I could see myself in it. We had only cold water and it froze regularly in the winter and water had to be carried from some more fortunate neighbor’s house then. The boys used to thaw the pipes under the house, using a gasoline lamp. That was for the minor freezes early in the winter. When it froze deep in the ground, the power company had to be called and the pipes thawed by electricity. Some people dug down to where the pipes were and built a fire and thawed them that way. We rather envied those whose pipes were deep enough not to be affected by the cold, and thus had water all winter without the worries of freezing.

The Home Comfort kitchen range was heated by coal fires, started with wood. It was the boys’ job to see that the wood box was filled as well as the coal bucket, a job not enjoyed by them. One time Wallace rigged up a rope and pulley arrangement for hauling the coal buckets from the shed to the house. Since he had to first fill them, then go up to the porch and pull the rope to bring them up one at a time, it hardly seemed a labor saving device, but he seemed to enjoy doing it that way. I suppose the boys took the ashes out also. At intervals the soot would accumulate and it was a dirty job (but one which I didn’t mind as I grew up) to remove it with a long-handled instrument made for that purpose. The soot was scraped first from the bottoms of the stove lids on the back, then from the space above the oven, down the sides and the back of the stove, and finally (the most tedious part of the job) from the space below the oven. The fire always burned better and the oven heated more satisfactorily when the soot had been cleaned out, so it was a rewarding job.

We had an electric iron, but since thrift was practiced to a painful degree on account of our poverty, we also had flatirons with a detachable handle, which were always on the back of the stove and moved to the hot part at the front when there was ironing to be done. If there was no fire, the electric iron would be used, but Mother and I usually managed to do some ironing when she was cooking, so as to use the heat from the stove and thus cut down on the electric bill. We usually had an old catalog to rest and clean the irons on when they were being used.

We had a kitchen cabinet which was used mostly for food. There was a bin where the flour was kept. It was put in at the top and removed at the bottom where there was a flour sifter, a very handy device. There was also a smaller bin for sugar, a metal container on one of the doors; a big bottom drawer for bread; two other drawers, one for silver and the other for cooking utensils; and a large cupboard at the bottom for cooking pans. Packaged foods, of which there were not so many at that time, were on the shelves of the upper part. There was a zinc covered top, which pulled out and was suitable for kneading bread, rolling biscuits and cookies, etc.

In the corner opposite the kitchen range was a tall wooden cupboard which held a miscellaneous assortment of hardware and odds and ends of things that had no other place. In the corner nearest the side-door was another similar cupboard, which held the dishes in the upper part. Towels and dishtowels were in the lower part, along with dishpans and other large cookware. As I recall, the cupboards were painted an ugly shade of light brown, as were the doors and other woodwork. The kitchen cabinet and table were stained and varnish finished. The floor was bare.

The kitchen door opened onto the side-porch where there was a small ice box for food that had to be kept cool. While we could seldom afford ice, food stayed cool since the porch roof kept the sunshine from hitting where the icebox stood.

In the dining room we had a large table with chairs, a large sideboard, and a combination china closet (or book case) and desk. As a town business man, I guess my father had “connections” and when the old Victor Club went out of business he acquired our dining and living room furniture (all fairly nice) before acute poverty set in.

We ate the evening meal, which we called “supper”, in the dining room at the big table with a tablecloth. Father always had a napkin in his special napkin holder. Somebody brought forth the rumor that my father ate first and not with the rest of the family, but that was not true. We all ate together, all nine of us. Many of our neighbors ate all their meals in the kitchen at an oilcloth covered table.

Mother’s sewing machine, a White Rotary, was in the corner of the dining room, usually opened and with a stack of sewing piled on it. She was a good seamstress and sewed most of the family clothes until the boys got too big for her to make their pants. She always sewed my clothes, making many things over from garments Aunt Isa gave her. She also did occasional sewing for the neighbors to pick up a bit of cash, a scarce item around there. As I grew older doing the family darning became my job, one I grumbled about, but didn’t really mind. I also was allowed to baste and take out bastings from other sewing, but never did learn much about sewing until I was grown.

In 1910 a change in our finances obliged us to move back to South Third. As long as I can remember, Father was a miner (leaser). I believe his grocery business was lost (gambled away) before we moved back to South Third Street. At one time Father also had an office uptown in what became the Post Office building, but I do not know what he did there.

I was about five years old and Ed about one year old at that time. About all I remember about the move was being allowed to ride on the big moving wagon, seated on one of our big leather chairs. The big Colorado Trading & Transfer Company coal wagons, hauled by huge horses, were the only means of transportation.

The place we moved into was two small houses (at 507 and 509 S 3rd St) joined together by a door-wide passage with a step up. Electricity and cold water piped into a sink with a drain emptying into the yard by the back stairs were the only modern features. The toilet (my mother insisted that “closet” was the correct word) was at the end of the yard in back of 509. The wood and coal shed was in back of 507. This place on South Third where we lived for the next ten years was a real come-down for the ones of the family who were old enough to realize the situation. A telephone (probably the only one on the block) was our one luxury.

In the main house (509) there was a big kitchen, a medium dining room, a living room, and one tiny bedroom which was Pearl’s. All heat was from coal and wood stoves.

There was always a fire in the kitchen stove which had a reservoir. “Fill the reservoir” and “fill the tea kettle” were constant warnings. With no hot water available as it is now by turning a faucet, having a kettle of hot water available was important; and to leave a teakettle empty on the hot stove was a condition not to be tolerated.

In the kitchen we had a large table which was Mother’s worktable (since there were no counters) as well as our dining table for breakfasts and lunches. There was a plain, unadorned sink with a mirror above it. I can remember looking forward to the day when I could see myself in it. We had only cold water and it froze regularly in the winter and water had to be carried from some more fortunate neighbor’s house then. The boys used to thaw the pipes under the house, using a gasoline lamp. That was for the minor freezes early in the winter. When it froze deep in the ground, the power company had to be called and the pipes thawed by electricity. Some people dug down to where the pipes were and built a fire and thawed them that way. We rather envied those whose pipes were deep enough not to be affected by the cold, and thus had water all winter without the worries of freezing.

The Home Comfort kitchen range was heated by coal fires, started with wood. It was the boys’ job to see that the wood box was filled as well as the coal bucket, a job not enjoyed by them. One time Wallace rigged up a rope and pulley arrangement for hauling the coal buckets from the shed to the house. Since he had to first fill them, then go up to the porch and pull the rope to bring them up one at a time, it hardly seemed a labor saving device, but he seemed to enjoy doing it that way. I suppose the boys took the ashes out also. At intervals the soot would accumulate and it was a dirty job (but one which I didn’t mind as I grew up) to remove it with a long-handled instrument made for that purpose. The soot was scraped first from the bottoms of the stove lids on the back, then from the space above the oven, down the sides and the back of the stove, and finally (the most tedious part of the job) from the space below the oven. The fire always burned better and the oven heated more satisfactorily when the soot had been cleaned out, so it was a rewarding job.

We had an electric iron, but since thrift was practiced to a painful degree on account of our poverty, we also had flatirons with a detachable handle, which were always on the back of the stove and moved to the hot part at the front when there was ironing to be done. If there was no fire, the electric iron would be used, but Mother and I usually managed to do some ironing when she was cooking, so as to use the heat from the stove and thus cut down on the electric bill. We usually had an old catalog to rest and clean the irons on when they were being used.

We had a kitchen cabinet which was used mostly for food. There was a bin where the flour was kept. It was put in at the top and removed at the bottom where there was a flour sifter, a very handy device. There was also a smaller bin for sugar, a metal container on one of the doors; a big bottom drawer for bread; two other drawers, one for silver and the other for cooking utensils; and a large cupboard at the bottom for cooking pans. Packaged foods, of which there were not so many at that time, were on the shelves of the upper part. There was a zinc covered top, which pulled out and was suitable for kneading bread, rolling biscuits and cookies, etc.

In the corner opposite the kitchen range was a tall wooden cupboard which held a miscellaneous assortment of hardware and odds and ends of things that had no other place. In the corner nearest the side-door was another similar cupboard, which held the dishes in the upper part. Towels and dishtowels were in the lower part, along with dishpans and other large cookware. As I recall, the cupboards were painted an ugly shade of light brown, as were the doors and other woodwork. The kitchen cabinet and table were stained and varnish finished. The floor was bare.

The kitchen door opened onto the side-porch where there was a small ice box for food that had to be kept cool. While we could seldom afford ice, food stayed cool since the porch roof kept the sunshine from hitting where the icebox stood.

In the dining room we had a large table with chairs, a large sideboard, and a combination china closet (or book case) and desk. As a town business man, I guess my father had “connections” and when the old Victor Club went out of business he acquired our dining and living room furniture (all fairly nice) before acute poverty set in.

We ate the evening meal, which we called “supper”, in the dining room at the big table with a tablecloth. Father always had a napkin in his special napkin holder. Somebody brought forth the rumor that my father ate first and not with the rest of the family, but that was not true. We all ate together, all nine of us. Many of our neighbors ate all their meals in the kitchen at an oilcloth covered table.

Mother’s sewing machine, a White Rotary, was in the corner of the dining room, usually opened and with a stack of sewing piled on it. She was a good seamstress and sewed most of the family clothes until the boys got too big for her to make their pants. She always sewed my clothes, making many things over from garments Aunt Isa gave her. She also did occasional sewing for the neighbors to pick up a bit of cash, a scarce item around there. As I grew older doing the family darning became my job, one I grumbled about, but didn’t really mind. I also was allowed to baste and take out bastings from other sewing, but never did learn much about sewing until I was grown.

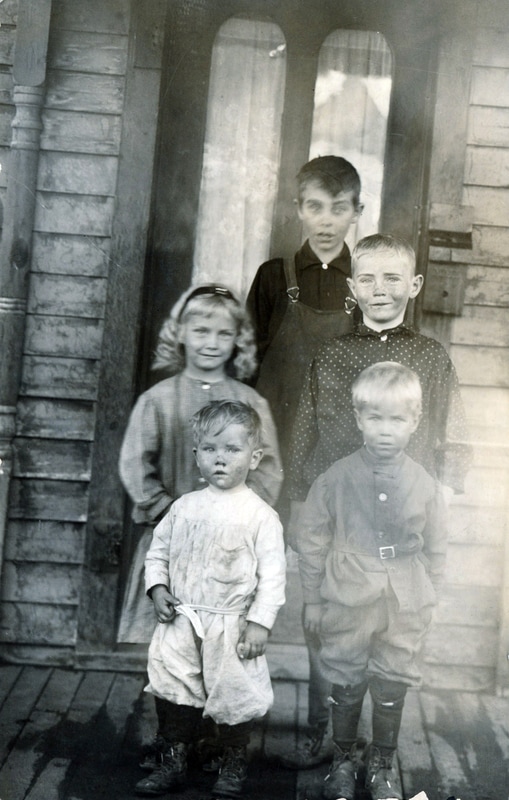

Moore children (about 1911) on front porch at 509 S 3rd Street in Victor. Back--Victor Harry (b 1896, d 1975). Middle--Gertrude (b 1905, d 1992), Howard (b 1899, d 1921). Front--John (b 1907, d 1919), Edward (b 1909, d 1972).

Moore children (about 1911) on front porch at 509 S 3rd Street in Victor. Back--Victor Harry (b 1896, d 1975). Middle--Gertrude (b 1905, d 1992), Howard (b 1899, d 1921). Front--John (b 1907, d 1919), Edward (b 1909, d 1972).

The living room was not large, perhaps 15 x 15, with a coal stove in the one corner resting on a piece of zinc made for that purpose. Furnishings included a throw rug, a leather-covered couch, and two big rockers on stands (one had wood arms and the other was all leather, rather cozy for snuggling with a book)—all acquired in more prosperous times.

When anybody was sick, he or she was allowed to have a bed made on the living room couch. Being of leather, it was hard to keep the blankets on and it was not the most comfortable place for sleeping, but it was handy for Mother to keep an eye on the patient instead of having to go into the other part of the house where the beds were.

The living room had one fairly large window and a front door leading onto a porch on ground level. There was a small fenced-in space where we had flowers in the summer. Mother had two pets among the flowers, which she kept indoors in pots in the winter and set outdoors in the summer. One was violets and the other was what she called a “pink” – a small version of a carnation, delicate pink in color and quite fragrant.

Pearl had a small bed room with a door from the kitchen (against which was her bed), a doorway from the dining room (which was covered by a cloth curtain), and a window opening on the back yard. This room was strictly off-limits to us children. In it there was a very small clothes closet, a single bed, a dresser and a chair.

The other “joined” house (507) consisted of five rooms including: two very small bedrooms where the four older boys slept; another bedroom where my parents and baby Edward slept; a room that was originally a kitchen, but we used it for a big clothes closet; and a fairly large former living room which held Father’s big desk and office chair as well as my bed (a large crib in which I slept until I was ten years old and Pearl left her room to me when she married). There was a stove in the room where I slept and in the winter a fire was built there in the evening to take the chill off. Otherwise that part of the house was kept closed off and not heated.

Our house was always untidy with dressers, sideboard and tables always covered. Mother simply did not have time to take care of those details with all the cooking, childcare, sewing, ironing, mending, and even sewing for others since Father’s income was uncertain. There were bare floors throughout the house, curtains at the windows, but no other refinements.

I was very matter-of-fact about our way of living and simply accepted it. It never occurred to me that the bad parts of it could be any other way. It was just our way and that was that. Probably my mother’s calm acceptance without complaining had a lot to do with it.

When anybody was sick, he or she was allowed to have a bed made on the living room couch. Being of leather, it was hard to keep the blankets on and it was not the most comfortable place for sleeping, but it was handy for Mother to keep an eye on the patient instead of having to go into the other part of the house where the beds were.

The living room had one fairly large window and a front door leading onto a porch on ground level. There was a small fenced-in space where we had flowers in the summer. Mother had two pets among the flowers, which she kept indoors in pots in the winter and set outdoors in the summer. One was violets and the other was what she called a “pink” – a small version of a carnation, delicate pink in color and quite fragrant.

Pearl had a small bed room with a door from the kitchen (against which was her bed), a doorway from the dining room (which was covered by a cloth curtain), and a window opening on the back yard. This room was strictly off-limits to us children. In it there was a very small clothes closet, a single bed, a dresser and a chair.

The other “joined” house (507) consisted of five rooms including: two very small bedrooms where the four older boys slept; another bedroom where my parents and baby Edward slept; a room that was originally a kitchen, but we used it for a big clothes closet; and a fairly large former living room which held Father’s big desk and office chair as well as my bed (a large crib in which I slept until I was ten years old and Pearl left her room to me when she married). There was a stove in the room where I slept and in the winter a fire was built there in the evening to take the chill off. Otherwise that part of the house was kept closed off and not heated.

Our house was always untidy with dressers, sideboard and tables always covered. Mother simply did not have time to take care of those details with all the cooking, childcare, sewing, ironing, mending, and even sewing for others since Father’s income was uncertain. There were bare floors throughout the house, curtains at the windows, but no other refinements.

I was very matter-of-fact about our way of living and simply accepted it. It never occurred to me that the bad parts of it could be any other way. It was just our way and that was that. Probably my mother’s calm acceptance without complaining had a lot to do with it.

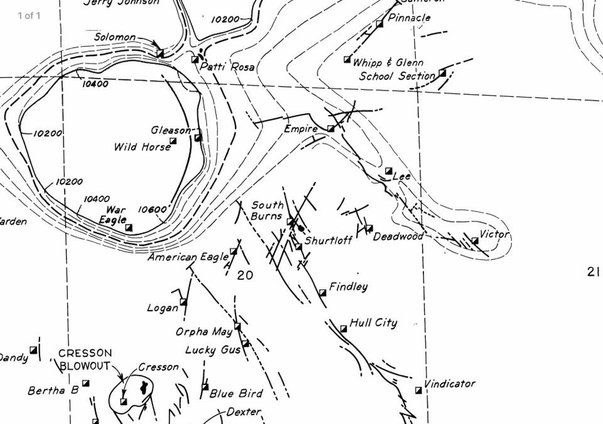

Map showing location of the Lucky Gus Mine (near bottom, center) where Father was a leaser.

Map showing location of the Lucky Gus Mine (near bottom, center) where Father was a leaser.

My Father

Father had made quite a bit of money leasing when I was small, then lost it all or lived it up. After our return to Third Street, we were very poor and keeping us provided with food, heat and clothing was a real struggle. Fortunately we owned the house where we lived.

I cannot remember a time when my father was not a miner (leaser), going to work early in the morning, coming home after four in the afternoon, carrying his lunch bucket with the thermos bottle. The first I remember of his working was at the Lucky Gus, one of the small mines on Bull Hill that he leased with the Anderson brothers. Father worked it by himself part of the time with a hand operated hoist and winch. He would climb down the shaft, fill the bucket with ore, climb up the ladder and pull the bucket up using the hand-operated hoist. On days when he did not hoist, he would drill underground, set the dynamite, light the fuse, climb up the ladder and wait for the shots to tell the dynamite had exploded. That was done the last thing in the day and nobody ventured underground again that day for fear of a delayed shot or falling rock.

Father had made quite a bit of money leasing when I was small, then lost it all or lived it up. After our return to Third Street, we were very poor and keeping us provided with food, heat and clothing was a real struggle. Fortunately we owned the house where we lived.

I cannot remember a time when my father was not a miner (leaser), going to work early in the morning, coming home after four in the afternoon, carrying his lunch bucket with the thermos bottle. The first I remember of his working was at the Lucky Gus, one of the small mines on Bull Hill that he leased with the Anderson brothers. Father worked it by himself part of the time with a hand operated hoist and winch. He would climb down the shaft, fill the bucket with ore, climb up the ladder and pull the bucket up using the hand-operated hoist. On days when he did not hoist, he would drill underground, set the dynamite, light the fuse, climb up the ladder and wait for the shots to tell the dynamite had exploded. That was done the last thing in the day and nobody ventured underground again that day for fear of a delayed shot or falling rock.

Lucky Gus Mine property where Harry Moore leased--upper right.

Lucky Gus Mine property where Harry Moore leased--upper right.

Father was always bringing home ore samples to roast or pulverize and “wash” to see if there was any gold in them. There were assay cups, clay cone shaped vessels with enough bottom to stand on. He would put them into the heart of a very hot fire and leave them until the rocks were red hot. This was done at night and they were left in the stove to cool after the fire died out. If there was gold in the rocks, it would pop out in little yellow bubbles. He had a big ore pan for washing the pulverized rock (done with a mortar and pestle). He would run water over the ore as he stood at the sink, carefully swishing the pan back and forth. The gold, if any, would stay at the bottom of the pan and show up as yellow flakes. Gold is heavier than the other material, which made it stay in the bottom of the pan. He had some small bottles containing the gold. Its actual value was not much, but it was pretty to look at, as were the roasted specimens.

My father and the Anderson brothers had worked together and made a lot of money. When the ore played out the Andersons had put their share into buying and operating the K. C. Market on North Third Street (which made them a good living). Father put his share back into the ground and for years he never gave up the idea there was still gold left in that property. But eventually he had to give up, and then worked a lease on the Golden Cycle at Altman and later one at the Portland. It seemed that if my father did have a good shipment, all the money went to pay bills, mostly to the grocery store, and there was never anything to spare for the little extras.

My father was a tall, good looking man—considered quite a dandy in his younger days, I was given to understand. He was bald, wore a moustache, and tried many advertised methods for regaining lost hair. I remember a large high cap (looked like metal), which he used to wear for a certain time each evening. I don’t know whether he used some ointment or lotion on his scalp, but the hair never grew. He was never fat, neat about himself and took his baths at the barbershop (which was equipped for it and our house wasn’t).

Father seldom wore dress clothes. Khaki pants worn tucked into his high leather laced boots and heavy work shirts were his usual garb and he always wore a hat, never caps, as many of the men did. Father’s coat was always a khaki, about hip length and lined completely, with pockets where he carried whatever he had to bring home—sometimes things he had bought at the store. He would buy luxuries that Mother wouldn’t, but not particularly things we children liked. He had champagne tastes on a beer income and liked oysters and other fancy fish when available.

My father was quite an indifferent parent and I have no recollection of his ever paying any attention to any of us children, except when he would come home on a good-natured drunk. Then he would play with us and put small change in his boots, then dump it on the floor for us to scramble after. When sober, he was very quiet, not grouchy, but never had anything to say. I can’t remember of his ever being angry or scolding us. He was oblivious to the noise of us children quarreling, which we did most of the time. It may be that my father used to take the older boys, Victor and Howard, hunting or fishing when they were small, but none of the younger children enjoyed that privilege.

Father was a bright man, though without formal education, and read a lot. Colliers and National Geographic were a part of our household as long as I can remember. He was not a handy man around the house and I don’t remember of his ever repairing anything that needed fixing. The only exception was putting half soles on the boys’ shoes. We had a last and stand and that was one thing Mother nagged to get done. Lack of money alone made him stoop to such indignity. Since a half sole could be purchased for a few cents, and a half sole put on by the cobbler up town cost much more, he was forced into it. I think I got my habit of being careful with equipment because of this fact that, as a child, once a thing was broken or worn out, that was it and there was not likely to be any repairs or replacement.

Father was intelligent, interested in world events and political issues, a follower of Teddy Roosevelt and active locally in Republican politics--a committeeman, judge in elections, etc. He was also a member of the Masonic Lodge (Past Master). While he had no musical talent that I know of, he marched with the band (at the head of the procession, wearing his uniform and waving his baton) when they gave their Saturday night concerts on Victor Avenue in the summer. He also liked to play certain noisy records (marches) on our old phonograph.

He was quite a ladies’ man, a gambler and drinker, which partly accounted for the fact that we were so poverty-stricken. However, there were some plusses in our home life. No profanity or vulgar language or “dirty stories” were allowed. My mother had precise ideas as to what was proper and my father was never profane.

During all of my growing-up years, we were poverty-stricken, kept fed and clothed only by the generosity of the merchants and Mother’s eternal working and saving. She sewed for the neighbors to earn what she could, in addition to doing everything (except washing once a week) for the family of nine people. If lack of funds bothered my father, I never knew about it. He said no man could keep as big a family as ours on wages, so he preferred to lease and always have the hope of making a fortune.

My father and the Anderson brothers had worked together and made a lot of money. When the ore played out the Andersons had put their share into buying and operating the K. C. Market on North Third Street (which made them a good living). Father put his share back into the ground and for years he never gave up the idea there was still gold left in that property. But eventually he had to give up, and then worked a lease on the Golden Cycle at Altman and later one at the Portland. It seemed that if my father did have a good shipment, all the money went to pay bills, mostly to the grocery store, and there was never anything to spare for the little extras.

My father was a tall, good looking man—considered quite a dandy in his younger days, I was given to understand. He was bald, wore a moustache, and tried many advertised methods for regaining lost hair. I remember a large high cap (looked like metal), which he used to wear for a certain time each evening. I don’t know whether he used some ointment or lotion on his scalp, but the hair never grew. He was never fat, neat about himself and took his baths at the barbershop (which was equipped for it and our house wasn’t).

Father seldom wore dress clothes. Khaki pants worn tucked into his high leather laced boots and heavy work shirts were his usual garb and he always wore a hat, never caps, as many of the men did. Father’s coat was always a khaki, about hip length and lined completely, with pockets where he carried whatever he had to bring home—sometimes things he had bought at the store. He would buy luxuries that Mother wouldn’t, but not particularly things we children liked. He had champagne tastes on a beer income and liked oysters and other fancy fish when available.

My father was quite an indifferent parent and I have no recollection of his ever paying any attention to any of us children, except when he would come home on a good-natured drunk. Then he would play with us and put small change in his boots, then dump it on the floor for us to scramble after. When sober, he was very quiet, not grouchy, but never had anything to say. I can’t remember of his ever being angry or scolding us. He was oblivious to the noise of us children quarreling, which we did most of the time. It may be that my father used to take the older boys, Victor and Howard, hunting or fishing when they were small, but none of the younger children enjoyed that privilege.

Father was a bright man, though without formal education, and read a lot. Colliers and National Geographic were a part of our household as long as I can remember. He was not a handy man around the house and I don’t remember of his ever repairing anything that needed fixing. The only exception was putting half soles on the boys’ shoes. We had a last and stand and that was one thing Mother nagged to get done. Lack of money alone made him stoop to such indignity. Since a half sole could be purchased for a few cents, and a half sole put on by the cobbler up town cost much more, he was forced into it. I think I got my habit of being careful with equipment because of this fact that, as a child, once a thing was broken or worn out, that was it and there was not likely to be any repairs or replacement.

Father was intelligent, interested in world events and political issues, a follower of Teddy Roosevelt and active locally in Republican politics--a committeeman, judge in elections, etc. He was also a member of the Masonic Lodge (Past Master). While he had no musical talent that I know of, he marched with the band (at the head of the procession, wearing his uniform and waving his baton) when they gave their Saturday night concerts on Victor Avenue in the summer. He also liked to play certain noisy records (marches) on our old phonograph.

He was quite a ladies’ man, a gambler and drinker, which partly accounted for the fact that we were so poverty-stricken. However, there were some plusses in our home life. No profanity or vulgar language or “dirty stories” were allowed. My mother had precise ideas as to what was proper and my father was never profane.

During all of my growing-up years, we were poverty-stricken, kept fed and clothed only by the generosity of the merchants and Mother’s eternal working and saving. She sewed for the neighbors to earn what she could, in addition to doing everything (except washing once a week) for the family of nine people. If lack of funds bothered my father, I never knew about it. He said no man could keep as big a family as ours on wages, so he preferred to lease and always have the hope of making a fortune.

Lulu Moore and her youngest sons, John and Edward, in front of their family home at 509 S 3rd Street.

Lulu Moore and her youngest sons, John and Edward, in front of their family home at 509 S 3rd Street.

My Mother

Mother wore a two-piece outfit for everything except dress-up. She would never have dreamed of going “up town” without changing into her suit or a dressy dress in the summer. She was a good seamstress and made most of our clothes.

When our family was more prosperous and lived in the Stratton house, my mother had a hired girl who helped with the household and children. After we moved back to South Third, the only household help she had was a woman who did the washing (on the board) every Monday, regardless of weather. I was told that when my father came home from work in the evening and found Mother still doing the laundry, they decided she deserved at least someone to do that.

Neighborhood women on South Third visited occasionally—always accompanied by a basket of mending and sometimes with recipes to exchange. For a while, my mother and Mrs. Nordquist each baked a double recipe of bread on baking day and exchanged loaves so they wouldn’t have to bake so often. In spite of all the years the women knew each other, they never used first names—it was always Mrs. Nordquist, Mrs. Trost, Mrs. Williams, etc.

Mother was a slow-moving rather heavy woman who suffered periodically from bronchial asthma. It did not follow hay fever as it did with most who had it. She had a powder which she burned in a saucer and inhaled the fumes, which made her cough and loosened the mucous which was having her gasping for breath. The powder smelled pretty bad and I remember how we kids used to complain about it, selfish little brats that we were. I can’t remember her ever being sick enough to be prevented from getting our meals except when she had the flu in 1919.

She just kept plugging along, doing everything except the washing. The cooking for nine of us, ironing in the days when there was no wash-and-wear, sewing, mending, baking all of our bread, routine housework, caring for the small children—all this kept her constantly busy. Even when resting briefly or visiting occasionally with neighbors, she always had some hand mending to pick up and work on. Mother should have insisted on us kids doing certain things, but about all she insisted on was help with dishes, table setting, and keeping the wood and coal hauled.

The boys did the chores outdoors. They also had helped with washing dishes up until the time I got old enough to do it. Wallace and I did the dishes until he rebelled for some reason and from then on, it was my job, which I delayed as long as possible every day. Mother had a rule that I was not allowed out of the house until the dishes were done and if I preferred to loaf around until time for the next meal, that was my loss. Of course I had to get the dishes done before the next meal, but never seemed to get up enough steam to do them first and have some time to myself. Mother got a kick out of telling about one little neighbor girl, younger than I, who came over late one afternoon and asked: “Miss Moore, can Gertrude come out to play after she does the dishes?”

Mother sometimes had severe headaches. She never complained that I remember, but used to fold a handkerchief and dampen it with spirits of camphor and tie it around her head. She endured much and we children were not much help. For sheer lack of time and energy, she was not a companion to us, though helpful in teaching us new skills. We were very poor and keeping us provided with food, heat and clothing was a real struggle.

My mother told of having had an old mattress taken out of a shed and we children played on it one afternoon. First my brother Wallace got scarlet fever (one of the older children had scarlet fever before and that was why the mattress was discarded). On the last day of his six weeks of quarantine I got it, so then we had to be quarantined another six weeks. At that time the quarantine was strictly enforced. Grocery orders were phoned in and the grocery boy left the things at the gate to be taken in. Nothing went out of the house or yard during that time. Father roomed at a hotel and the children old enough to be in school had to stay home. Poor Mother was isolated.

People avoided houses with a big quarantine sign (red and black, I believe). When I was older we kids would walk around the block if we could to keep from going near a quarantined house. The law required that the quarantine sign be put up whenever there was any contagious disease and nobody was supposed to leave or go in. But since we had measles so many times, Mother finally just quit reporting it and we didn’t have to be quarantined.

While her reading time was limited, Mother subscribed to the Pictorial Review (a woman’s magazine with fiction and articles) and Ladies’ Home Journal. I eagerly awaited the Pictorial Review because it had paper dolls, which it was my privilege to cut out. I never played with them as some girls did. I had real dolls, lots of them, probably because I was the only girl.

Our food was of the plainest, although it included many things we regard almost as luxuries at today’s prices. Ham, which is a luxury today, was regular. Mother would cook a whole ham, which we ate for a couple of days, then the rest would be used for Father’s sandwich in his lunch bucket and when the piece got too small to slice, she would cut off the scraps and cook them (ground) with water, vinegar and mustard to make deviled ham, which also was used for sandwiches.

We had beans, sometimes just boiled and sometimes baked by Mother’s father’s recipe. They were boiled one day and the next day mixed with seasonings and molasses, put into a baking dish and covered with strips of bacon (which was bought always by the slab) and baked in a moderate oven (coal stove) for several hours. She also made Boston brown bread by her father’s recipe. Eaten hot, with lots of butter, it was delicious. It took a couple of hours of steaming, then baking for about half an hour to dry out the top.

We ate potatoes, of course, and ground round, which Mother insisted on rather than hamburger. We had quite a bit of cabbage, which my father was fond of, and liked to have cooked until it was brown. I had to get away from home to learn there was any other way to cook it. It is quite indigestible when cooked so long.

We used little in the way of canned goods—mostly peas, corn and tomatoes. And packaged goods were in short supply at this time. The only dry cereals I can remember are corn flakes and shredded wheat. Long-cooking oatmeal was used all the time. My mother would cook it at night and let it stand in the double boiler all night on the stove, and then heat it again in the morning. Quick cooking and instant cereals were unheard of. Buying was done in quantity–a hundred pounds of potatoes and flour, two dozen eggs, two pounds of butter. Few things were packaged; quantities were kept in bins and barrels at the grocery store. Mother used the flour sacks for dish towels, or underwear or slips for me.

Without transportation, shopping was easy compared to now. A clerk from the grocery store, “the order man”, came around every morning to get the housewife’s order, and later in the day it was delivered, anything from a cake of yeast to a hundred pounds of anything. Even with things being ordered in quantity, there were few days when nothing was needed. The grocery stores, of which there were four or five at this time, were open from seven in the morning until six at night, staying open till nine on Saturday and “pay-day” evenings. Pay-day was once a month at the mines–on the 10th. Of course, the leasers got their money whenever the check came from the mill. Compared to today’s shopping spree, it was simple. No endless trudging through the store, picking out items, comparing prices, loading up shopping baskets, standing in line at check-out counters, lifting the heavy sacks into the car and carrying them into the house when one gets home. Life was indeed simpler, if not so luxurious. Later, phone calls replaced the order man and finally the lady of the house phoned her order in and it was delivered, even as long as when my oldest daughter [Nancy] was married in 1953, and even later.

We had a few other sources of supply aside from the K.C. Market where we traded. For milk, we bought two quarts daily, which was delivered by Mrs. Myers, aided sometimes by her son Howard. She had a cart pulled by a horse and had her dairy a few miles from town on the other side of Straub. The milk was in large cans and she measured out two capfuls into our “milk pan”. Sanitation was not such an item then. I guess there may have been bottles for milk then, but Mother was loyal to Mrs. Myers, who was a hard working woman and needed the business.

There also was a man who came to town at intervals selling “hominy and horseradish”, which was his call as he came down the street. There were vegetable peddlers during the summer. One especially, George Demery, was a regular and so tight he would break a bean in two (so my mother said) if the scales showed a whisper over the mark being paid for. Another regular was an old lady who made quilts. She sold chances on them from house to house. Mother always bought one, but never won. The old lady was quite a gossip, so Mother wasn’t too anxious to have the children around when she came. It seems that somebody came with piccalilli (a relish of chopped pickled vegetables and spices), but the hominy and horseradish man may have brought that also.

Mother wore a two-piece outfit for everything except dress-up. She would never have dreamed of going “up town” without changing into her suit or a dressy dress in the summer. She was a good seamstress and made most of our clothes.

When our family was more prosperous and lived in the Stratton house, my mother had a hired girl who helped with the household and children. After we moved back to South Third, the only household help she had was a woman who did the washing (on the board) every Monday, regardless of weather. I was told that when my father came home from work in the evening and found Mother still doing the laundry, they decided she deserved at least someone to do that.

Neighborhood women on South Third visited occasionally—always accompanied by a basket of mending and sometimes with recipes to exchange. For a while, my mother and Mrs. Nordquist each baked a double recipe of bread on baking day and exchanged loaves so they wouldn’t have to bake so often. In spite of all the years the women knew each other, they never used first names—it was always Mrs. Nordquist, Mrs. Trost, Mrs. Williams, etc.

Mother was a slow-moving rather heavy woman who suffered periodically from bronchial asthma. It did not follow hay fever as it did with most who had it. She had a powder which she burned in a saucer and inhaled the fumes, which made her cough and loosened the mucous which was having her gasping for breath. The powder smelled pretty bad and I remember how we kids used to complain about it, selfish little brats that we were. I can’t remember her ever being sick enough to be prevented from getting our meals except when she had the flu in 1919.

She just kept plugging along, doing everything except the washing. The cooking for nine of us, ironing in the days when there was no wash-and-wear, sewing, mending, baking all of our bread, routine housework, caring for the small children—all this kept her constantly busy. Even when resting briefly or visiting occasionally with neighbors, she always had some hand mending to pick up and work on. Mother should have insisted on us kids doing certain things, but about all she insisted on was help with dishes, table setting, and keeping the wood and coal hauled.

The boys did the chores outdoors. They also had helped with washing dishes up until the time I got old enough to do it. Wallace and I did the dishes until he rebelled for some reason and from then on, it was my job, which I delayed as long as possible every day. Mother had a rule that I was not allowed out of the house until the dishes were done and if I preferred to loaf around until time for the next meal, that was my loss. Of course I had to get the dishes done before the next meal, but never seemed to get up enough steam to do them first and have some time to myself. Mother got a kick out of telling about one little neighbor girl, younger than I, who came over late one afternoon and asked: “Miss Moore, can Gertrude come out to play after she does the dishes?”

Mother sometimes had severe headaches. She never complained that I remember, but used to fold a handkerchief and dampen it with spirits of camphor and tie it around her head. She endured much and we children were not much help. For sheer lack of time and energy, she was not a companion to us, though helpful in teaching us new skills. We were very poor and keeping us provided with food, heat and clothing was a real struggle.

My mother told of having had an old mattress taken out of a shed and we children played on it one afternoon. First my brother Wallace got scarlet fever (one of the older children had scarlet fever before and that was why the mattress was discarded). On the last day of his six weeks of quarantine I got it, so then we had to be quarantined another six weeks. At that time the quarantine was strictly enforced. Grocery orders were phoned in and the grocery boy left the things at the gate to be taken in. Nothing went out of the house or yard during that time. Father roomed at a hotel and the children old enough to be in school had to stay home. Poor Mother was isolated.

People avoided houses with a big quarantine sign (red and black, I believe). When I was older we kids would walk around the block if we could to keep from going near a quarantined house. The law required that the quarantine sign be put up whenever there was any contagious disease and nobody was supposed to leave or go in. But since we had measles so many times, Mother finally just quit reporting it and we didn’t have to be quarantined.

While her reading time was limited, Mother subscribed to the Pictorial Review (a woman’s magazine with fiction and articles) and Ladies’ Home Journal. I eagerly awaited the Pictorial Review because it had paper dolls, which it was my privilege to cut out. I never played with them as some girls did. I had real dolls, lots of them, probably because I was the only girl.

Our food was of the plainest, although it included many things we regard almost as luxuries at today’s prices. Ham, which is a luxury today, was regular. Mother would cook a whole ham, which we ate for a couple of days, then the rest would be used for Father’s sandwich in his lunch bucket and when the piece got too small to slice, she would cut off the scraps and cook them (ground) with water, vinegar and mustard to make deviled ham, which also was used for sandwiches.

We had beans, sometimes just boiled and sometimes baked by Mother’s father’s recipe. They were boiled one day and the next day mixed with seasonings and molasses, put into a baking dish and covered with strips of bacon (which was bought always by the slab) and baked in a moderate oven (coal stove) for several hours. She also made Boston brown bread by her father’s recipe. Eaten hot, with lots of butter, it was delicious. It took a couple of hours of steaming, then baking for about half an hour to dry out the top.

We ate potatoes, of course, and ground round, which Mother insisted on rather than hamburger. We had quite a bit of cabbage, which my father was fond of, and liked to have cooked until it was brown. I had to get away from home to learn there was any other way to cook it. It is quite indigestible when cooked so long.

We used little in the way of canned goods—mostly peas, corn and tomatoes. And packaged goods were in short supply at this time. The only dry cereals I can remember are corn flakes and shredded wheat. Long-cooking oatmeal was used all the time. My mother would cook it at night and let it stand in the double boiler all night on the stove, and then heat it again in the morning. Quick cooking and instant cereals were unheard of. Buying was done in quantity–a hundred pounds of potatoes and flour, two dozen eggs, two pounds of butter. Few things were packaged; quantities were kept in bins and barrels at the grocery store. Mother used the flour sacks for dish towels, or underwear or slips for me.

Without transportation, shopping was easy compared to now. A clerk from the grocery store, “the order man”, came around every morning to get the housewife’s order, and later in the day it was delivered, anything from a cake of yeast to a hundred pounds of anything. Even with things being ordered in quantity, there were few days when nothing was needed. The grocery stores, of which there were four or five at this time, were open from seven in the morning until six at night, staying open till nine on Saturday and “pay-day” evenings. Pay-day was once a month at the mines–on the 10th. Of course, the leasers got their money whenever the check came from the mill. Compared to today’s shopping spree, it was simple. No endless trudging through the store, picking out items, comparing prices, loading up shopping baskets, standing in line at check-out counters, lifting the heavy sacks into the car and carrying them into the house when one gets home. Life was indeed simpler, if not so luxurious. Later, phone calls replaced the order man and finally the lady of the house phoned her order in and it was delivered, even as long as when my oldest daughter [Nancy] was married in 1953, and even later.

We had a few other sources of supply aside from the K.C. Market where we traded. For milk, we bought two quarts daily, which was delivered by Mrs. Myers, aided sometimes by her son Howard. She had a cart pulled by a horse and had her dairy a few miles from town on the other side of Straub. The milk was in large cans and she measured out two capfuls into our “milk pan”. Sanitation was not such an item then. I guess there may have been bottles for milk then, but Mother was loyal to Mrs. Myers, who was a hard working woman and needed the business.

There also was a man who came to town at intervals selling “hominy and horseradish”, which was his call as he came down the street. There were vegetable peddlers during the summer. One especially, George Demery, was a regular and so tight he would break a bean in two (so my mother said) if the scales showed a whisper over the mark being paid for. Another regular was an old lady who made quilts. She sold chances on them from house to house. Mother always bought one, but never won. The old lady was quite a gossip, so Mother wasn’t too anxious to have the children around when she came. It seems that somebody came with piccalilli (a relish of chopped pickled vegetables and spices), but the hominy and horseradish man may have brought that also.

Labor Day Bronco Busting Rodeo in Victor. Photo contributed by LaJean Greeson.

Labor Day Bronco Busting Rodeo in Victor. Photo contributed by LaJean Greeson.

The Children--My Brothers & Sisters

Victor Harry. Our parades were as big an item in our lives as the Rose Bowl is to Pasadena. There were the usual floats, maybe half a dozen, and the horses and the band. There was a rodeo of sorts in which my brother Vic usually had a part. He loved to ride the bucking broncos and I was always afraid he would be thrown off and get hurt. These events were usually held on the west end of Victor Avenue. We kids would sit on the high steps of some two-story house up there where we gathered a sunburn.

Wallace. He was the worker in the family. It seems that we were always on the ragged edge so far as money went. Wallace worked summers for Lebers, who had a dairy, and he also had paper routes. With his donkey (Betsy) and a little cart, he hauled wood for our use and sold some to neighbors. When he was in high school he worked before and after hours and on Sundays at what we called the Book Store—across the street from the post office. I remember that one of the Baptist church members stopped in there one Sunday morning and bawled him out for working on Sunday, disregarding the fact that she was using his services on Sunday! It seems that he never went to Sunday school or church after that.

Howard. We had mail delivery until I was in high school. Tom Bateman was our carrier and a friend of Howard’s. One time when those two boys were out hunting or target practicing with the 22s, Howard shot a bullet that ricocheted and hit Tom in the eye, which caused him to lose it.

Gertrude. We children had some toys that would be worth a fortune with today’s fad for antiques. The boys had some little tin soldiers, an iron bank made in the shape of a square building, and some toy railroad cars. As the only girl in the family, I had more than my share of dolls. My favorite was a small celluloid one called Helen Louise. This was more like a baby than the china dolls, which were more prevalent then. Mother had a very large rag doll with a china head, which she had when she was a little girl. It was named Martha Adelaide and had black hair (china) and pretty pink cheeks. She had kid feet and legs part way up. My mother had a few of the clothing items that she used for the doll. She had another smaller one, but it became broken or lost along the way. I wasn’t a very devoted mother to my dolls. Periodically, I’d become conscience-stricken and dress them up and put them to sleep in whatever place I was using for a dollhouse then. It was the desire of my life to have a wicker doll buggy for them, similar to the ones some people had for their babies. I never did get the doll buggy.

I recall one Christmas when I got my usual doll and one of my brothers broke it before the day was over. I felt myself to be the most abused of mortals, even though I had more dolls than any girl I knew.

Speaking of Christmas – there was one year when more than life itself I wanted a knit bonnet with a little veil coming down over the face. Some of the other girls had one and I suppose I thought it would make me beautiful. But though I had asked Santa Claus for it, it wasn’t there Christmas morning. That may have been the time I stopped believing in him–when I recognized Wallace’s handwriting on the note Santa sent me in reply to my requests. I was a very gullible child.

Victor Harry. Our parades were as big an item in our lives as the Rose Bowl is to Pasadena. There were the usual floats, maybe half a dozen, and the horses and the band. There was a rodeo of sorts in which my brother Vic usually had a part. He loved to ride the bucking broncos and I was always afraid he would be thrown off and get hurt. These events were usually held on the west end of Victor Avenue. We kids would sit on the high steps of some two-story house up there where we gathered a sunburn.

Wallace. He was the worker in the family. It seems that we were always on the ragged edge so far as money went. Wallace worked summers for Lebers, who had a dairy, and he also had paper routes. With his donkey (Betsy) and a little cart, he hauled wood for our use and sold some to neighbors. When he was in high school he worked before and after hours and on Sundays at what we called the Book Store—across the street from the post office. I remember that one of the Baptist church members stopped in there one Sunday morning and bawled him out for working on Sunday, disregarding the fact that she was using his services on Sunday! It seems that he never went to Sunday school or church after that.

Howard. We had mail delivery until I was in high school. Tom Bateman was our carrier and a friend of Howard’s. One time when those two boys were out hunting or target practicing with the 22s, Howard shot a bullet that ricocheted and hit Tom in the eye, which caused him to lose it.

Gertrude. We children had some toys that would be worth a fortune with today’s fad for antiques. The boys had some little tin soldiers, an iron bank made in the shape of a square building, and some toy railroad cars. As the only girl in the family, I had more than my share of dolls. My favorite was a small celluloid one called Helen Louise. This was more like a baby than the china dolls, which were more prevalent then. Mother had a very large rag doll with a china head, which she had when she was a little girl. It was named Martha Adelaide and had black hair (china) and pretty pink cheeks. She had kid feet and legs part way up. My mother had a few of the clothing items that she used for the doll. She had another smaller one, but it became broken or lost along the way. I wasn’t a very devoted mother to my dolls. Periodically, I’d become conscience-stricken and dress them up and put them to sleep in whatever place I was using for a dollhouse then. It was the desire of my life to have a wicker doll buggy for them, similar to the ones some people had for their babies. I never did get the doll buggy.

I recall one Christmas when I got my usual doll and one of my brothers broke it before the day was over. I felt myself to be the most abused of mortals, even though I had more dolls than any girl I knew.

Speaking of Christmas – there was one year when more than life itself I wanted a knit bonnet with a little veil coming down over the face. Some of the other girls had one and I suppose I thought it would make me beautiful. But though I had asked Santa Claus for it, it wasn’t there Christmas morning. That may have been the time I stopped believing in him–when I recognized Wallace’s handwriting on the note Santa sent me in reply to my requests. I was a very gullible child.

Lulu Moore with youngest sons, John and Edward, on S 3rd Street.

Lulu Moore with youngest sons, John and Edward, on S 3rd Street.

John. My brother John, two years younger than myself, died from the 1918 flu epidemic. It had let up and the schools opened just one day. I happened to sit next to a boy who was coming down with it. I wasn’t very sick, but most of the rest of the family were, my mother especially. We had a nurse who came in to help with the meals and do what was necessary. Mother was not well enough to attend the funeral. I always felt guilty for having brought the disease to them all. Lots of people died from the flu that year in Victor as every place else. I think that epidemic was world-wide.

Edward. While we lived at 509 S 3rd, Ed got scarlet fever and the house was quarantined, a custom at that time. For the duration of his illness Pearl and Wallace and I got to stay at Aunt Isa’s house at the Portland Mine. It was a mansion according to our way of living. Pearl had a chance to boss me and she did it, insisting I eat everything whether I liked it or not. Wallace had a paper route and got up early in the morning for it. We all walked to school, but occasionally a man who did errands at the mine would bring us home at night. I suppose I carried a lunch, but don’t remember.

Pearl taught at the Garfield School. When she married, probably about 1914, I got to visit her in Denver for a week. Her husband, Snowden, was working someplace else as a mining engineer. I had a great time riding streetcars and going to City Park, which was near. She and Snowden moved to Arizona on a job, where Snowden, Jr. was born. Later they returned to Denver where Snowden had various jobs, and Foster was born.

Edward. While we lived at 509 S 3rd, Ed got scarlet fever and the house was quarantined, a custom at that time. For the duration of his illness Pearl and Wallace and I got to stay at Aunt Isa’s house at the Portland Mine. It was a mansion according to our way of living. Pearl had a chance to boss me and she did it, insisting I eat everything whether I liked it or not. Wallace had a paper route and got up early in the morning for it. We all walked to school, but occasionally a man who did errands at the mine would bring us home at night. I suppose I carried a lunch, but don’t remember.

Pearl taught at the Garfield School. When she married, probably about 1914, I got to visit her in Denver for a week. Her husband, Snowden, was working someplace else as a mining engineer. I had a great time riding streetcars and going to City Park, which was near. She and Snowden moved to Arizona on a job, where Snowden, Jr. was born. Later they returned to Denver where Snowden had various jobs, and Foster was born.

|

Isa Elizabeth was the first child of our family to be born in a hospital—1920. Dr. Elliott, a former Army doctor, officiated. Mother was 48 at the time and there was a gap of 11 years between the next older (Edward) and Isa. I was 15 at the time and the happiest person on South Third Street to at last have a baby sister of my own. Before that I had “borrowed” the neighbor babies to wheel around the flat in front of our house. I objected much when other children who had small babies in their own homes tried to keep me from that task.

My brother Ed had whooping cough when Isa was an infant and she caught it from him. She was very sick and I think I was the only one who knew she was going to live. Praying for her was probably the first I ever did. She became so run down that she had to have a special formula. Today’s dieticians are horrified at the idea, but at that time Eagle Brand was considered baby food, so she had that mixed with strained oatmeal gruel and was fed by spoon. I guess it was all right, because she recovered. |

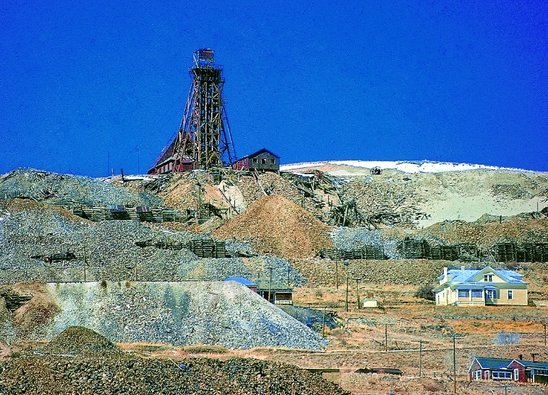

The Portland Mine where Aunt Isa & Uncle Frank Smale lived in a house that seemed like a palace to us poor relations who lived down the hill. Uncle Frank was Superintendent of the Portland Mine.

The Portland Mine where Aunt Isa & Uncle Frank Smale lived in a house that seemed like a palace to us poor relations who lived down the hill. Uncle Frank was Superintendent of the Portland Mine.

Aunt Isa & Uncle Frank Smale’s House

My younger sister was named after my father’s sister, Isa Mary Moore. Aunt Isa was married to Frank Smale, the Superintendent of the Portland Mine—one of the “big jobs” in the District. I don’t know whether it was a regular thing, but I remember one Christmas when we went to Aunt Isa and Uncle Frank’s big house at the Portland Mine for the day. Since I had gone to visit some of the neighbors and was not there when the family was ready, they left me. Again I felt myself most abused and ran all the way up the hill to the mine.

My younger sister was named after my father’s sister, Isa Mary Moore. Aunt Isa was married to Frank Smale, the Superintendent of the Portland Mine—one of the “big jobs” in the District. I don’t know whether it was a regular thing, but I remember one Christmas when we went to Aunt Isa and Uncle Frank’s big house at the Portland Mine for the day. Since I had gone to visit some of the neighbors and was not there when the family was ready, they left me. Again I felt myself most abused and ran all the way up the hill to the mine.

Mine headframe for the Portland 2. The yellow superintendent's house, where Isa & Frank Smale once lived, still stands today. Photo circa 1950 contributed by Chuck Clark ©.

Mine headframe for the Portland 2. The yellow superintendent's house, where Isa & Frank Smale once lived, still stands today. Photo circa 1950 contributed by Chuck Clark ©.

Aunt Isa and Uncle Frank's house was a palace by our standards. The glassed-in front porch was filled with lots of potted plants. There was a large living room—in the corner of which stood a big tree, beautifully decorated with many colorful ornaments, much different from the indestructible tinsel and paper decorations we had at home. In the library, adjoining the living room, the walls were lined with books. There was a couch, big leather chairs and a fireplace—a most comfortable spot which I loved.

The large dining room with wide windows on the east had a built-in buffet, a long table beautifully set, and china closets full of delicate dishes—all very grand to us poor relations from down the hill. From the dining room windows one could see the little town of Goldfield, which then had a fair population, even its own school, but was going downhill even then; and before I finished school there were no schools in Goldfield and few families.

One door out of the dining room led into a small hall, from which opened two bedroom doors, one bathroom, the stairway to the second floor, and a door into a “modern” kitchen. On the second floor were two bedrooms and Uncle Frank’s “study”. Their house was a palace, indeed, from our point of view.

I don’t remember much about Uncle Frank, but Aunt Isa was a small, neat person with dark hair. She was a Christian Scientist, of which my mother did not approve. Aunt Isa and Uncle Frank had no children. They eventually moved to Riverside, California where she continued to work as a Christian Science practitioner, living to the age of 100. Aunt Isa and her sister, Hazel, lived together in her Riverside mansion after their husbands died. She was still a most gracious host into her 90’s when I visited her occasionally with my daughter Nancy who lived in Mojave. Aunt Isa gave her namesake, my younger sister, a baby diamond ring before she passed.

The large dining room with wide windows on the east had a built-in buffet, a long table beautifully set, and china closets full of delicate dishes—all very grand to us poor relations from down the hill. From the dining room windows one could see the little town of Goldfield, which then had a fair population, even its own school, but was going downhill even then; and before I finished school there were no schools in Goldfield and few families.

One door out of the dining room led into a small hall, from which opened two bedroom doors, one bathroom, the stairway to the second floor, and a door into a “modern” kitchen. On the second floor were two bedrooms and Uncle Frank’s “study”. Their house was a palace, indeed, from our point of view.

I don’t remember much about Uncle Frank, but Aunt Isa was a small, neat person with dark hair. She was a Christian Scientist, of which my mother did not approve. Aunt Isa and Uncle Frank had no children. They eventually moved to Riverside, California where she continued to work as a Christian Science practitioner, living to the age of 100. Aunt Isa and her sister, Hazel, lived together in her Riverside mansion after their husbands died. She was still a most gracious host into her 90’s when I visited her occasionally with my daughter Nancy who lived in Mojave. Aunt Isa gave her namesake, my younger sister, a baby diamond ring before she passed.

Lincoln School -- large two-story building in the foreground at the end of S 3rd Street. As children we were warned never to go into this building after it was closed and abandoned. Lehr photo, circa 1928.

Lincoln School -- large two-story building in the foreground at the end of S 3rd Street. As children we were warned never to go into this building after it was closed and abandoned. Lehr photo, circa 1928.

Our Neighborhood

We lived on South Third Street in a block full of children. Somebody once said there were 50 in that block. It was fairly level and was called “The Flat”. There were few places in town that were not hilly. There were six Moores, six Nordquists, six Bowdens, three Georges, three Trosts, three Rileys, three Larsons, two Axelsons, two Snyders, one Williams, five Quirks, two Polkinghorns, and seven Millers. At one time the Claussens lived next door—that was Clara and her sister and two brothers. When they grew up, Clara married my brother Victor and they lived nearby many more years.